Conversion Narratives

by Nitin Govil

[ PDF version ]

When Julia Roberts announced her conversion to Hinduism in Elle magazine last year, she joined the ranks of American celebrities famous for their public professions of religious affiliation. From Mel Gibson’s Catholicism, John Travolta and Tom Cruise’s Scientology, and Richard Gere’s Tibetan Buddhism, to George Lucas’s “Buddhist Methodism,” Madonna’s Kabbalah, and Marie Osmond’s Mormonism, religious stardom aligns public expression with private belief. For many Hollywood celebrities, religion incarnates the star as the product of missionary and mercenary worlds, an embodied connection between the sacred and the profane. For Hollywood’s most publicly manufactured subjects, religious devotion references an essential, inalienable self that is both inside and outside commoditization. The shuttling between the interiority and exteriority of celebrity characterizes the work of stardom. That is how something as intangible as belief can testify to the material reality of the star.

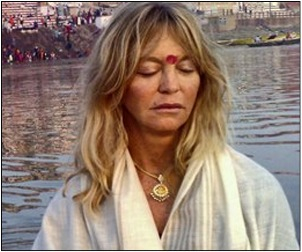

So perhaps it’s not surprising that much of the conversation around Julia’s conversion has been about intention: was her Hinduism driven by faith or was it a gendered brand accessory to stardom, like tattoos in Anglicized Devangari script, henna, and bindis? Was Julia’s Hinduism driven by conviction or was it a publicity stunt—in short, was it about belief or work (fig. 1)? Such queries are common to the culture industry of stardom, which frames (and monetizes) a gap between authenticity and performance. The theater of religious intimacy seems ideal for the staging of stardom because, as Chris Rojek claims, the cultish identification mobilized by celebrity worship is substantiated in the language of sacralization.[i] We are fascinated with celebrity religion because it seems to compensate for the lack of substance associated with stardom. The flash of the paparazzi camera marks our initiation as acolytes into the rites of celebrity worship. We revere stars even as they pray to other heavenly bodies.[ii]

Figure 1. Julia Roberts meets Swami Dharmdev at Hari Mandir Ashram in Pataudi, near New Delhi, September 2009. Source: Associated Press.

Perhaps we can leave the question of Julia’s sincerity to her and her god(s). Taking seriously Media Fields Journal’s current engagement with labor and mobility, I’d like to suggest that Julia’s Hindu conversion is part of a much broader cultural logic, located in the anxieties about identification and alterity in the international division of labor in the screen industries.[iii] Julia’s public conversion demonstrates how self-presentation and brand management has become the front-stage work of celebrity. Ernest Sternberg notes that in the labor of “personal composition,” stars can position themselves in a market, “mobilizing demeanor and conduct so they reference a realm of meaning that consumers find evocative.”[iv] The self as brand increasingly defines the celebrity commodity, and religious identification offers a particularly potent form of self-branding, especially when it is associated with a public rite of conversion.[v]

Throughout the history of Hollywood celebrity, stars publicly committed to family and charity in order to manage the tension between temperance and excess. But contemporary stardom, fueled by the fiction of instantaneous access and the hyperreality of global infotainment, demands new metrics of intimacy. It is not enough that stars have a “private” life that is both distinct from and connected to our everyday; we must know their motivations and dreams as well. Our knowledge of the personal life of the star is rooted in this engagement with the interiority of desire. In Hollywood’s globally mediated stardom, religion—along with transnational child adoption—helps to extend the brand afterlife of the celebrity commodity.[vi] At the same time, the karma of celebrity folk negotiates the pressures of cultural labor as it is dispersed across various histories and places. That is why Angelina Jolie’s difficult experience in shooting A Mighty Heart (dir. Michael Winterbottom, 2007) in India 2006, which led to Johnny Depp’s refusal to shoot Shantaram (in development) on location in Bombay, still couldn’t derail plans to marry Brad Pitt in a Hindu ceremony in Jodhpur. The 2011 wedding is to be presided over by the couple’s spiritual guru, Ram Lal Siyag, who recently gave them a mantra to recite in order to rejuvenate their relationship.

For decades, India has functioned as a location for spiritual transcendence and personal transformation for the Hollywood glitterati (fig. 2). Recently, however, with accelerating institutional contact invigorating financial and distribution arrangements between Los Angeles and Mumbai, more and more American stars are coming to India for work. At first, most of them seemed to be stars of a faded sort, working in India in order to resuscitate their flagging careers. With their stardom tarnished by flops, bad financial planning, and personal controversy, actors like Sylvester Stallone and Denise Richards were redeployed in the service of high-profile Hindi productions like Kambakkht Ishq (dir. Sabir Khan, 2009). This kind of stunt casting suggested that Bollywood was emerging as a dumping ground for Hollywood stardom.

Figure 2. Goldie Hawn performs Ganga Aarti (the hymn dedicated to the sacred river) at the Dashashwamedh Ghat in Varanasi on a 2009 trip. Source: Screen, November 10, 2009.

Working with Nicolas Cage and other worn-out Hollywood stars also provides Hindi film directors like Vidhu Vinod Chopra with the opportunity to break into English language production. Alongside fallen A-listers, emerging American film stars from Brandon Ruth to Ali Larter are taking their turns on the Bollywood stage. And now, more established Hollywood actors like Drew Barrymore, Mickey Rourke, and John Travolta are interested in collaborating with Hindi film producers, illustrating the productive potential of a crossover celebrity that is celebrated by American and Indian media alike. Far from serving as the graveyard of Hollywood stardom, Bollywood has emerged as a site for Hollywood reincarnation. Hollywood labor is reborn in India.

So the stage seemed set for the highest profile rebirth of all. The Indian and international press were delighted that Julia Roberts had worn a vermillion bindi during a January 2009 visit to the Taj Mahal, seeing it as a gesture of cultural respect.[vii] Of course, it helped that she was a yoga devotee and had named her production company “Red Om Films.” Raised by Catholic and Baptist parents in Georgia, but having occasionally practiced Hinduism for over a decade, Julia Roberts converted in India in autumn 2009 while filming Eat, Pray, Love (dir. Ryan Murphy, 2010), the adaptation of Elizabeth Gilbert’s novelized advertisement for spiritual tourism. Reportedly, Roberts’s full commitment to Hinduism was secured by a meeting with Swami Dharam Dev, who renamed her three children in honor of the gods for the duration of her Indian shooting schedule. Some of the global faithful were incredulous at their high-profile convert, but Roberts was welcomed by the Universal Society of Hinduism (located in America).

Despite all the fanfare, solving the logistical challenges of a foreign shoot in India trumped the consideration Julia might have shown to her newly found brethren. During the filming of Eat, Pray, Love, for example, hundreds of security guards attached to the production shut down Navaratri festivities at a temple near Delhi while the film shot on temple grounds. Adherents wishing to perform their darshan were denied the opportunity even to see Roberts in the act of filming. Roberts might have publicly hoped to be reincarnated as “something quiet and supporting” after the hustle-bustle of celebrity life, but her film production obstructed a local religious observance. What’s curious here is less the disregard of local practice or the compromise of religious belief by professional obligation. After all, Hollywood celebrity demonstrates that the distinction between religion and work is hardly sacrosanct. What I’m interested in is how the global economy of Hollywood manifests itself through the narrative of conversion. While stardom’s negotiation between the elite and the everyday was afforded by Julia’s newfound religion, Hindu conversion became a metaphor for the mobility of Hollywood’s cultural labor.

Julia’s film shoot was not the first time that Hinduism has been imbricated in the work of Hollywood celebrity. In fact, beginning in the 1920s, Hinduism became associated with the ongoing stratification of labor in the American film industry. Hollywood’s labor aristocracy became popularly known as a “caste system.” In 1923, Myrtle Gebhart noted that, “not alone in India does the caste system flourish, but in plebeian Hollywood, that gingham child-town now beginning to wear her silks and jewels as though she’d been used to them all her life.”[viii] By the early 1930s, John Scott could claim that, “like India, Hollywood’s caste system admits of little social climbing in the studios.”[ix] And by the late 1930s, Hedda Hopper, Hollywood’s famous gossip columnist, used the metaphor of caste to address systematic wage inequity in Hollywood as well as the intractability of social reform (fig. 3). “People tear their hair over the shame of Mother India and the cruelty of her caste system," noted Hopper, “but it would take a better man than Mahatma Gandhi to bridge the chasm between a $200 a week actor, and one who earns $2,000…The caste system has caused more tragedies in Hollywood than have scandals.”[x]

Pre-war American film journalism raised public awareness of worker exploitation in the film industry by using caste to characterize the growing labor-management crisis in Hollywood’s “Golden Era.” That a modern industry like film could be so dominated by the “backwardness” of caste signaled Hollywood’s social depravity to an American public that still recalled the scandals and moral excesses of the 1920s. At the same time, using “caste” instead of “class” allowed critics to address structural labor inequality without inviting difficult associations with Marxist terminology at a time when Hollywood was popularly assumed to be running over with communists. Caste became a way for writers to identify a labor-management problem without politicizing it.

Figure 3. Hedda Hopper weighs in on Hollywood’s “caste problem.” Source: The Washington Post, December 18, 1938.

So, in a sense, Hollywood labor was characterized as Hindu well before Julia Roberts announced her newfound devotion. But while Hinduism accentuates the contemporary transnational mobility of Julia Roberts’s stardom, historically the journalistic evocation of Hinduism in the vernacular use of caste accounted for a pervasive lack of mobility in Hollywood. Although separated by decades, both of these labor configurations invoke Hindu conversion in order to frame the discourse of Hollywood labor (im)mobility.

Curiously, another conversion strategy is being used to shore up future labor relations between U.S. and Indian media. Sparked by the global success of films like Avatar (dir. James Cameron, 2009), and building on longstanding outsourcing relationships between Indian FX houses and Hollywood studios, global media industries are capitalizing on 3D conversion.[xi] Reliance MediaWorks recently announced a tie-in with In-Three, a California-based 2D-3D conversion company to reanimate both new and back-catalog Hollywood films in a process called “dimensionalization.” And the Indian post-production/camera rental company Prime Focus rebranded its North American facilities in 2009, premiering a 2D-3D conversion service called View-D. The work of Indian studios adding a third dimension to Hollywood films is projected to cut 50% off the usual costs of 3D conversion.

Julia’s conversion helped reanimate her stardom by adding another dimension to her celebrity. In a similar way, by reanimating American cinema, Indian dimensionalization offers new life to Hollywood. Both conversion narratives demonstrate a firm belief (or was that faith?) in the rejuvenating potential of a cultural labor that is mobile on a transnational scale.

Notes

With thanks to Lauren Berliner, Pawan Singh, and the editors for their comments.

[i] Chris Rojek, Celebrity (London: Reaktion Press, 2001).

[ii] Ironically, Richard Dyer’s influential text on stardom does not elaborate on the question of celebrity faith, noting only that religion is among the many “social categories in which people are placed and through which they have to make sense of their lives.” Richard Dyer, Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society (New York: Routledge, 2004), 16.

[iii] For more on the emergence of the Hollywood’s international division of cultural labor, see Toby Miller, Nitin Govil, John McMurria, Richard Maxwell, and Ting Wang, Global Hollywood 2 (London: BFI, 2005).

[iv] Ernest Sternberg, “Phantasmagoric Labor: The New Economies of Self-Presentation,” Futures 30, no. 1 (1998): 3-28.

[v] For more on the commodity logic of self-branding, see Sarah Banet-Weiser, AuthenticTM: Political Possibility in a Brand Culture (New York: New York University Press, forthcoming).

[vi] For more on the industries of circulation, repackaging, and repurposing that enable the “afterlife” of media commodities, see Shawn Shimpach, Television in Transition: the Life and Afterlife of the Narrative Action Hero (Malden: Blackwell, 2010).

[vii] See, for example, “Hindus in US Admire Julia Roberts for Sporting Bindi During Taj Mahal Visit,” Asian News International, January 26, 2009; and “Hindus Warmly Welcome Julia Roberts to Hinduism,” Hindustan Times, August 5, 2010.

[viii] Myrtle Gebhart, “Caste Rules in Hollywood: Many Different Social Planes are Developing in the Life of the Cinema Players,” Los Angeles Times, October 7, 1923, 33.

[ix] John Scott, “Hindu Caste System Has Parallel Among Actors: Yawning Gaps Separate Star From ‘Unwashed’ Extra, While Social Climber Stranded at Start,” Los Angeles Times, February 28, 1932.

[x] Hedda Hopper, “On Hollywood’s Caste and Class System,” The Washington Post, December 18, 1938.

[xi] Avatar’s director, James Cameron, recently announced an interest in working with Indian 3D animators on a film adaptation of either the Ramayana or the Mahabharata, the Sanskrit epics at the heart of the Hindu canon. After taking a dip in the Ganges at the Hindu pilgrimage site of Haridwar on a recent trip to India, Cameron claimed that, “it was nice to feed in the spirituality, nice to share in the belief system. You do feel a little something for sure.” Quoted in Prashant Singh, “Indian Epic on Cameron ‘Hit List’,” India Today, December 12, 2010.

Nitin Govil is Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication at the University of California, San Diego. The co-author of Global Hollywood (2001) and Global Hollywood 2 (2005), he is currently completing two books, one on Hollywood in India, called Orienting Hollywood, and another on the Indian film industries, with Ranjani Mazumdar.

Post a Comment

Post a Comment