Mapping Documentary: Roundtable with Filmmaker Ido Haar and Film and Media Studies Scholar Janet Walker in Conversation with David Gray and Jade Petermon

One of the featured events at Contested Territories, the 2011 Media Fields Conference at UC Santa Barbara, was a screening of Israeli filmmaker Ido Haar’s 2007 documentary 9 Star Hotel. The film follows a group of Palestinian workers who regularly and clandestinely cross the Green Line into Modi’in, Israel, a fast-growing city between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. The men risk detainment on a daily basis to work at construction sites, providing the labor necessary to keep pace with the city’s growth. The film quietly addresses the politics surrounding the militarization and contestation of the border between Israel and the occupied West Bank. The film’s observational style, as well as Haar’s willingness to move with and be moved by his subjects, opens it to spatial analysis. The film opens with shots of the workers running across a busy highway, eluding Israeli police, and foreshadowing the questions of borders and access that populate the later conversations of these same workers. The dialogues that run through the film show the workers’ awareness of their position in relation to formal and informal economies of labor and belonging. The move toward spatial analysis in the humanities takes up these same issues.

Haar was invited to campus by Janet Walker, who had visited various locations with him as research for the essay “‘Walking through walls’: Documentary Film and Other Technologies of Navigation, Aspiration, and Memory” (forthcoming in Trauma and Memory in Israeli Cinema, edited by Boaz Hagin and Raz Yosef [London: Continuum]). Walker’s essay uses 9 Star Hotel to argue for a spatial turn in both trauma studies and documentary analysis. This proposed and enacted spatial methodology includes traveling to the sites of filming, various forms of mapping, and textual analysis of the film. The combination of Walker’s essay, Haar’s UCSB residency and Media Fields presentation, and the coordinated “Documentary and Space” issue of Media Fields Journal sparked the idea for the four of us, all keenly interested in questions of spatial and documentary practice, to have a conversation. We were also interested in exploring the ethics and politics of collaborative scholarship. We sat down in early May 2011, three of us in Janet Walker’s office in Santa Barbara, and Ido Haar connected by Skype from Tel Aviv.

—David Gray and Jade Petermon

Figure 1. Janet Walker and Ido Haar visit the location of 9 Star Hotel (photo by Steve Nelson)

David Gray: I think it’s appropriate that we’re doing this over Skype even though we tried to meet in person, just because of the nature of your own interaction originally. I wanted to start by asking Ido to speak a little bit about how you originally came to the project 9 Star Hotel, and whether you knew from the beginning you would want go out to the site where the workers lived and spend extended periods of time with them there. Was that part of the plan from the beginning?

Ido Haar: No, it started when I was thinking about making a film that would be relevant to the political and social situation here in Israel, and I began to look for subjects. After doing a very personal film and looking inside to my family, to my close circle, the moment that I finished Melting Siberia (2004) I felt that now I can’t do it any more. I just need to start to look outside.

I grew up in the area where the film takes place and my parents still live there. I used to go every weekend to visit, and I saw those men running across the highway and disappearing into the forest or over the hills. And this is actually how it started. I found myself walking around those forests that I know since I was a child and discovering this kind of terminal where thousands of Palestinians come from the West Bank, from the Occupied Territories, down the hills. Many of them would go in cars to different places inside Israel. Many others kept walking to the city of Modi’in where they worked in construction. I knew immediately that this was the film I would make. It would be about this place, this terminal. I will meet those workers and go to different places inside Israel and tell a story about Israel, with different episodes. I had even started doing that; I had met some workers inside Israel and was shooting very nice scenes there.

And then one day one of the workers I had met told me about this place near the city of Modi’in where the workers were sleeping in “graves.” That’s the way he described it. He meant like sleeping containers. I asked him to take me there, and the moment I saw this place and met the people there, I really understood that this was where I wanted to stay and this was the story I wanted to tell: about that community and those two characters [the film’s protagonists Ahmed and Muhammad] and also about the place…

Figure 2. Three stills from 9 Star Hotel

Janet Walker: You had mentioned the proximity of your parents’ home in interviews, so I was aware of that already. But suddenly it seemed like a sharper realization in the context of the (Auto)biographical Documentary seminar we were co-teaching.

IH: Yes, this is the backyard of my house, my village where I grew up.

JW: Melting Siberia is all about your family and finding family (you did end up traveling from Israel to Siberia) and then 9 Star is all about people whose lives are very different from your own. But yet there is a geographical connection. In a way, the films are about the same area from two different prospects.

DG: Janet, how did you find this film and decide to research and write about it? And how did you first meet Ido?

JW: I went looking for a film I hoped existed, only 9 Star far exceeded my ability to imagine. I was in Israel to present a talk on “Documentaries of Return,” focusing on films about Holocaust survivors returning to their villages or to the camps, and also post-Katrina documentaries about people struggling to rebuild in New Orleans. The location of the conference—the Tel Aviv International Colloquium on Cinema and Television Studies—inspired me to make the link between the cases of Katrina and Israel/Palestine, and also to think not only about displacement and return, but about occupation as well. In fact, professor/filmmaker Judd Ne’eman welcomed us with a story of his boyhood in pre-1948 Palestine and a call to end the Occupation. The next day I walked into the terrific Tel Aviv video store, The Third Ear, asking for documentaries of return (as if that were already a recognizable category) from Israel or Palestine. They enthusiastically recommended 9 Star Hotel.

After watching it, I began poring over the map, identifying Modi’in, a major, and—as 9 Star amply illustrates—growing city between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. Of course everybody in the region knows where to find it, and I was substantially less knowledgeable. But I was curious to know precisely where and how the workers were coming in; which part of the Green Line they were crossing—and that was something that wasn’t widely known; not even to a local like Ido.

I realized this could be a delicate question since, for obvious reasons, the workers might wish to maintain the secrecy of their route, and Ido would likely be committed to that as well. But I felt that one would be limited in studying the film’s presentation of space and place without knowing the geography of the location. This is not to essentialize the territory; I’m very much a follower of critical human geography’s major insight that, while the physical features of land and sea are manifestly present and tangible, geographical knowledge is nevertheless a profoundly epistemological regime. Spaces are always constructed by geopolitical impulses and, certainly, by filmic representation as well. Given a film about Palestinian workers clandestinely “infiltrating Israel” (as the opening titles explain) but at the same time hired by Israeli bosses and owners—a key case of multiple inhabitation of a contested and supposedly bifurcated territory—awareness of the contours of the physical area seemed eminently necessary. Even in such a marvelously observational film, the combination of shots creates the place that the documentary (like all or most situated documentaries) seems only to follow and photograph. So I had a need to know where (and when) the shots were taken to understand how they were put together and the implications of that constructed, filmic space.

This is work you simply cannot do without the help of one or more of the people closely involved in the film’s production!

Ido was filmmaker-in-residence at the Jacob Burns Center and I importuned them to forward my email query. He responded that very day, with an “OK, sure, no problem, I’ll talk to you.” We spoke initially by phone, but realized quickly that Skype would be our way. For one thing, I wanted to be able to talk and point at maps. So, in preparation for our first conversation, I got a high three-legged stool out of the closet, and placed my laptop on the flat seat, opening it to face the big screen monitor in my living room. I called up Google Earth and asked, “OK, Ido, see this map on the monitor? Where were you running with the workers?” And he replied, “I can’t see the map on the your monitor” [laughter]. Do you remember any of this, Ido?

IH: Sure, everything.

JW: But you couldn’t make it out over Skype. Just like when I had been trying to fly down in Google Earth and get to the spot; resolution was lacking. So we started grabbing Google pages and emailing them back and forth to each other. I was nervous it would be too much to ask. But I wrote up the description of the first thirty-five shots, emailed it to Ido with the Google pages, and said, “OK, could you map the camera positions?” And he did! Later he let slip that it had taken a couple hours of his time.

Figure 3. Map of 9 Star Hotel’s opening camera positions, created by Greg Eliason and Janet Walker from the prototype by Ido Haar

From the mapped camera positions I saw that even this documentary, so concentrated on a particular place, was indeed constructed from disparate shots. It became obvious that the shots are not spatially contiguous, as they would be if taken by a cameraperson placing one foot after the next. Even the crucial “sneaking in” sequences had been put together from footage shot from different vantage points, over the course of a year or more.

DG: This brings us to the mapping process itself. There are those maps of the camera positions and also the imagined maps you created of Ido’s movements. And then there are the maps using Google Earth and, in addition, those derived from alternative sites showing where the former Palestinian villages were in relation to what was filmed. I wanted to hear a little about what was important about the actual mapping process from Janet, and then also to hear from Ido about whether the maps change the way that you think about the film.

JW: Well, as you know, contemporary documentary studies was born (this will be quick, don’t worry), with the idea that all films are fiction. At a certain moment in documentary history, the moment, in the sixties and into the seventies, say, when you had this incredible enthusiasm for portability, cheapness, cable sync and then crystal sync, and you had the possibility of making a film like Ido’s where you’re portable, you can move, you’re able to run along with the workers and carry the camera and get sync sound; at the moment when you had those possibilities, there was also this realization in our field that documentaries are largely “fictive” (Michael Renov’s word). You have characters and narrative and you have rising action and falling action. But what really strikes me these days is that even when there were important advances in documentary studies such as critically-informed close textual analysis, usually what would be noted would be composition or figure movement or eye-line matching. These analyses were still pretty indeterminate as to where, longitudinally and latitudinally, actions actually took place. Now I am of the conviction that the “where” matters hugely, even though, as I said before, the where is also a construct. And so this is this shift—from “all films are fiction; I’m going to look at character and narrative in documentary” to “what about place; in what ways is place fictive as well?”—that interests me now; that I think renders documentary analysis crucial for thinking about current issues of the local and the global.

I started cruising all around in Google Earth. And I started researching the history of the 9 Star footprint. When in Israel, the film scholar Linda Dittmar had taken me along on a trip with the organization Zochrot to map and commemorate one of the many depopulated and ruined Palestinian villages (this particular one was located near Jerusalem). Later, contemplating the film, I wondered where the families of the Modi’in workers came from originally. According to Ido, most are not people whose families originated inside the boundaries of Israel today; a lot of them are from families long established in what is now the West Bank. So I knew I wasn’t pointing to particular individuals in the film when querying who used to live in this area that is now barren—around Modi’in and the smaller towns in Israel and the settlements that are going up across the Line in the Occupied Territory—but to other Palestinian families.

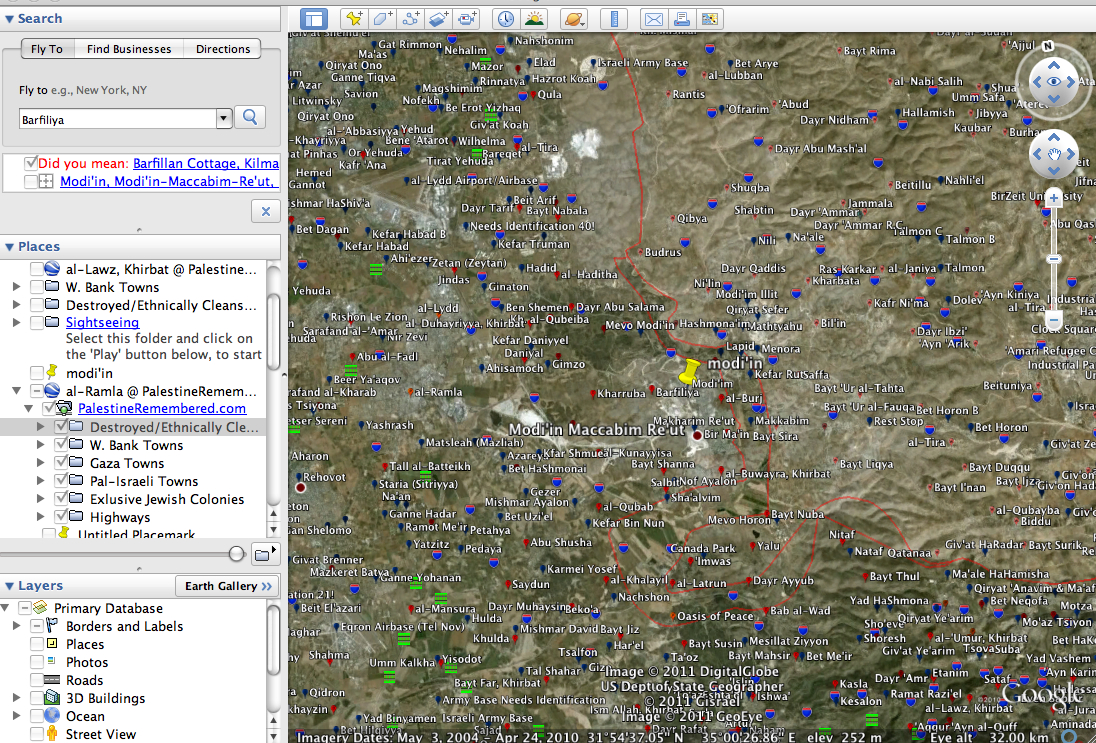

I got a printed historical map that showed the villages that had existed in this particular area prior to 1948. It’s just incredible. There were small villages, of maybe 500, 600, or 1,200 people, all around where the workers were living in their “9 Star Hotel.” But when I typed the village names into Google Earth, the application didn’t recognize them. I then found the site “Palestine Remembered,” and, as you were mentioning, David, imported the information into Google Earth, laying it over my maps.

Figure 4. Screen capture of Google Earth with village locations imported from Palestine Remembered

When I got a second invitation to Israel two years later, I figured I’d go if I could also meet Ido and travel to the “9 Star Hotel.” And because there was so much at stake in breaking the academic boycott of Israel—a boycott I can understand even though, for me, the opportunity to learn about and support the left in Israel wins out—I could only justify going to Israel if I took cognizance of the whole situation and visited the West Bank and Ramallah as well.

I told Ido, “I’m coming, and I’m free on May 29th.” And he said immediately, “I will take you there.” Just like that. I had figured he’d point me in the right direction and I’d rent a car. But he said, “No. I will take you there.”

Ido, in your film there’s this moment when you see two of the guys walking down the hill, and they’re passing through what seems once to have been a cleared field. You can see that it’s all green in the center of a rectangle of rocks. I wondered if this could have been the field of a former village. I tried really hard to spot remains of this kind via Google Earth, but you just can’t get close enough to discern anything like that. So I asked Ido if any of the workers, or he himself, had thought about the fact that there had been a number of villages in close proximity to one another in that area.

Figure 5. Screen capture from 9 Star Hotel

IH: Yes, Janet’s research, for me brought a totally different layer that I wasn’t aware of while I was shooting the film. Of course, I was aware in general of the history of the land and what’s happened in Israel. But I hadn’t really thought about it, or even tried to locate exactly where those villages were. I remember even one day, walking with a couple of workers, and walking through this ruin that definitely belonged to one of the villages that used to be there. But I didn’t even think about it. Because you see those kinds of ruins in so many places in Israel.

JW: Did they think about it?

IH: No. No, it was so casual in a way. All over Israel you see ruins that used to be Palestinian houses. Until I talked to Janet, I think, I didn’t really understand this aspect of the situation.

Jade Petermon: Ido, in Janet’s article she maps what she calls “directionality vectors,” the way that you and Ahmed travel across borders. This mapping brings up a number of questions, like who belongs, who’s visible, and it calls into question the borders that structure the lives of the workers, in particular. How did you feel, or did you feel at all that you were crossing borders in making the film? Not only actual physical borders, but also, in terms of being Israeli and making this film.

IH: Of course physically I felt it, and also when I was sneaking with the workers, and hiding with them; I definitely felt it. Even though in some way I’m sad because I know that if I were to get caught, probably nothing big would happen. But I remember it being very tense. You know, suddenly they are running, suddenly someone is shouting and they need to tell me to lie down. So I definitely had that feeling, which was in a way trying to identify what they are going through.

And in terms of other borders, you know it always was a question, even if I would get caught, of these things I know about the workers. I know that they are illegal, and I’m kind of cooperating with them. I remember one of my fears was if suddenly I will hear someone talking about terrorism, or something illegal that they know about. And I knew for sure that I would have to go and do something with this information. I remember those questions during the filming. It was an issue, definitely, of me being Israeli there in a community that is all Palestinian. I don’t know if it’s a matter of crossing borders, but yes, it’s definitely something.

JW: Why don’t the police just wait at the road where the workers cross on a Sunday morning when they’re all arriving at the job site?

IH: That’s the biggest question. At that time there was the policy of one eye open, one eye closed. Because there were so many workers, there were thousands and thousands, and someone had to build those houses. I always say, if the police really wanted to catch them, they could be there. But I do remember that there were times that the police were on that road, in that area. The workers used to hide in the forest for hours and hours until the police left, and then they would sneak across. But even when the police were there, the workers could always find another place to cross. They would go one km away, and then cross the highway. They did it so many times, and they had so many solutions for any kind of problem that would suddenly appear.

JW: What did you think when you saw those imaginary maps that I made with the help of Greg Eliason of everywhere you could go, like your apartment in Tel Aviv, the Sam Spiegel Film and Television School in Jerusalem, and then the places where you couldn’t go, or weren’t supposed to go? And from the workers’ side, everywhere they went? And how the two routes intersected? Of course, I got it all wrong, because I was using fragments of information, sparse data points, and then just extending the line across. For example, I have no idea how you got to Yatta, what road you took.

IH: Me neither [laughs]. I went there with a driver who is Palestinian, so I can’t really tell you.

Figure 6. Maps by Greg Eliason and Janet Walker

JW: How did you have the courage to do that?

IH: No, I have so many friends that do it every day, from all the human rights organizations. And also I knew that even if I were to be caught, I wouldn’t go to jail. It would not be considered a huge crime. It’s just that Israel can’t be responsible for the well-being of any Israeli that goes into those territories.

JW: And you went to Ahmed’s home?

IH: Yes, Ahmed and Muhammad. I went twice.

DG: Did any of that make it into the film? It’s not there, right?

IH: No. When I was shooting there, I was sure it would be. But when I tried to put it in, it felt so unconnected, I decided just to leave it out. It’s a story about a place, so when I tried to include this other place, it felt like it wasn’t connected.

JW: You were saying that when Palestinians have viewed the film, the men think, “we know all this” and the women think, “so that’s where our men go.” The men go off, carrying their bedrolls and pillows and provisions. The film gives the women access to spaces they don’t experience physically.

DG: I would like to hear from both of you about how much the location had changed since the filmmaking when you went back and visited? Also, what was the importance for you, Janet, of actually traveling to these sites?

IH: The location has changed a great deal. The distance between the site and the city was much longer than it is today since more houses and neighborhoods have been built. I remember it used to take ten minutes to walk and now it’s about five minutes.

JW: Also, a major concrete installation has been built over the wadi, gated with bars and a padlock. A new road crossing the bridge leads up along the hill—well inside the Green Line—hemmed in by a double row of electrified fencing. And Ido pointed out a row of trees [on the right], just below the road.

Figure 7. Installation and road over the wadi; trees obscuring an electrified fence (photos by Steve Nelson)

IH: Because Israelis are going to picnic on the weekends with kids, sitting there in nature and they don’t want to see those kinds of fences, they put trees and plants.

JW: Both for aesthetic reasons and to hide the security infrastructure. In the film the men anticipate and discuss the building of the fence. They know it won’t be long before they are blocked from entering Israel at this spot. A few more months of work...

From the audience, Judy Meisel, who is a survivor of Stutthof concentration camp, talked about how, now, there’s a problem in Mo’din because the Israelis are importing Thai and Chinese workers and then deporting their children who are born in Israel. She spoke up for workers rights, inspired by the film.

In answer to the second part of your question, David, I felt I had to go there and everywhere for this “Mapping Documentary” project. I have to put my feet on the ground, in the spot. It’s in large part to pay respect to those who are displaced and those for whom the terrain is charged with meaning; and to ally with local activist organizations.[i] And I definitely learn from “being there.” But I would be really uncomfortable privileging that form of knowledge acquisition over the other investigative techniques.[ii]

JP: Do either of you have anything you want to say in closing?

JW: That 9 Star Hotel opened my eyes to this sense of the shared space and spatial mobility, and also made me recognize that documentary scholars definitely need to talk to filmmakers—and we have a great chance to do so. Of course not all documentary filmmakers are as generous as Ido. Here I am, this middle-aged woman traipsing around through gravel and thistles, and Ido’s lifting up the barbed wire so I can squeeze through. Now that’s an unusual circumstance. But I really do think for scholars of documentary it’s key to talk to filmmakers. They are right there and maybe don’t mind talking to us either. What do you think?

IH: You work so hard for those projects and there are a lot of reviews and every time when someone in the academic world writes about it, it’s something new for me also. Like I said, the mapping of ruined villages in your project really opened up a different aspect that I wasn’t aware of. I think most of the people that I know would love for their projects to raise this kind of discussion.

JW: I wanted to bring Ido here to UC Santa Barbara to reciprocate the kindness he showed me in Israel. And he said, “even in Israel, I thought you were being kind to me to write about the film.” So that’s what kind of guy he is. He thought what he was doing for me was me doing something for him.

JP and DG: Well thank you so much!

Notes

[i] Phaedra C. Pezzullo’s brilliant book, Toxic Tourism: Rhetorics of Pollution, Travel, and Environmental Justice (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2007), presents an on-site research methodology and findings of deep significance and activist commitment.

[ii] See Walker’s discussion of Mr. Death: The Rise and Fall of Fred A. Leuchter, Jr. (Errol Morris, 1999) as an example of a case where a person physically present at a site (Auschwitz-Birkenau) is shown to be less knowledgeable about its history than a historian studying the blueprints. Trauma Cinema: Documenting Incest and the Holocaust (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 176-88.

David Gray is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His research interests include documentary, trauma, and memory studies. He is currently working on a dissertation on postdictatorial documentary film and videos in Argentina and Chile. David is the current Coordinating Editor of Media Fields Journal, and will be co-editing, with Jade Petermon, a forthcoming issue on memory and space.

Ido Haar is an Israeli film and television director, cinematographer, and editor whose documentaries 9 Star Hotel (2007) and Melting Siberia (2004; released theatrically in Israel) have realized worldwide success. 9 Star Hotel has screened at over 70 international film festivals and garnered over a dozen awards and prizes including Best Documentary Film at the 22nd Munich International Documentary Film Festival; Best Film, Human Rights Competition, Buenos Aires 9th International Festival of Independent Cinema; and, for Haar himself, the Best Director Award at the Israeli Documentary Filmmakers' Forum Competition. Haar has edited multiple episodes of the highly praised Israeli TV series In Treatment and the forthcoming post-Katrina documentary I’m Carolyn Parker directed by Jonathan Demme. Currently affiliated with the Jacob Burns Film Center in New York, he is completing a new film on the relative impacts of a volunteer army versus compulsory service.

Jade Petermon is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She received her B.A. in African and Black Diaspora Studies from DePaul University in 2008. Jade’s research and teaching interests include: film and television history and theory, new media technologies, women of color cultural productions, trauma studies, popular culture and cultural studies. Jade is currently working on a dissertation project entitled, “Traumatizing (In)Visibility: Re-Reading Black Women’s Cultural Production.” This project seeks to flesh out the relationship between trauma and visibility in cultural productions created by black women.

Janet Walker is Professor of Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where her affiliations include the Environmental Media Initiative of the Carsey-Wolf Center. Author of Trauma Cinema: Documenting Incest and the Holocaust and co-editor with Bhaskar Sarkar of Documentary Testimonies: Global Archives of Suffering, her current project, “Mapping Documentary,” seeks to bring spatial consciousness and cartographic methods inspired by critical human geography to bear on documentary film studies.

Media Fields Journal

Media Fields Journal