“Opening A Certain Poetic Space”: What Can Art Do for Refugees?

Saturday, January 7, 2017 at 2:03PM

Saturday, January 7, 2017 at 2:03PM Katarzyna Marciniak

[ PDF Version ]

Opening 1

“We are trying to do positive action: by opening a certain spirit, a certain poetic space, we can at least hope to change how we think about the problem.”

Ai Weiwei, commenting on the refugee crisis

Figure 1. Ai Weiwei.

Chinese dissident artist, Ai Weiwei, employing his art to comment on the current Syrian refugee crisis, placed his fully dressed body on a pebbled beach, close to water, on the Greek island of Lesbos (Figure 1). His eyes are closed and his face is turned toward the camera. The image, produced in collaboration with photographer Rohit Chawla, meant to recreate another image circulated on the internet in fall 2015 and widely commented upon: that of Aylan Kurdi, a Syrian toddler who drowned off the coast of Turkey. Weiwei’s pose mimics the pose of the child, visually taking us back to the original photograph. Various online magazines that published Kurdi’s image did so with a warning alerting the readers that they were about to see distressing material. And indeed, the devastatingly haunting photograph of a lifeless Syrian child—one that Jacques Ranciere might call “the intolerable image,” intolerable because “too intolerably real”—has often been referred to as a defining symbol of the dangerous plight of refugees trying to reach the shores of Europe, hoping for hospitality. [1] And yet the image of a dead child—a sickening confrontation with the death of a three-year-old—undercuts this hope, showing the morbid reality of border regimes and border deaths that has affected so many refugees. The Washington Post reported that Weiwei’s photograph was conceived for the exhibition at the India Art Fair. Co-owner of the India Art Fair, Sandy Angus, remarked: “It is an iconic image because it is very political, human and involves an incredibly important artist like Ai Weiwei …The image is haunting and represents the whole immigration crisis and the hopelessness of the people who have tried to escape their pasts for a better future.” [2]

While it is possible to read Weiwei’s image as a powerful instantiation of a politics of mourning and a performance enunciating what Judith Butler calls “grievability,” [3] predictably, the image sparked controversy and Weiwei’s artistic experiment has been called “callous,” “careerist,” and even “egotistical victim porn.” [4] Many have perceived it as an insensitive exploitation, self-promotion, and unethical appropriation. Niru Ratnam, for example, writing for The Spectator, referred to Weiwei’s image as “crude,” and “thoughtless”: “To pose as Kurdi is a crude piece of identification with the dead boy.” [5] Yet, condemning Weiwei’s performance somehow feels too easy: such condemnations try to cleanse artistic practice and privilege some proper form of politicized art, or a proper form of representation while approaching trauma. Rather, I see his image as engaging with what Maurice Stierl has termed “necropolitical violence.” [6] Stierl uses this concept in the context of what he calls “grief-activism”: the role of grieving as “a transformative political practice” vis-à-vis migrants’ deaths as “evidence of unwantedness” and the symbol of Europe’s violent border practices. [7] Weiwei’s reenactment does not ask the viewers to remember Aylan Kurdi, since the boy’s death has certainly already been imprinted on the memory of many people globally who paid attention. Instead, the performative dimension of Weiwei’s reenactment—in which, like many performance artists, he uses his body—underscores the point that approaching artistic representations of trauma is always highly contentious, overdetermined, and aporetic.

Speaking of the contentious nature of art when approaching difficult subjects, I am reminded of the controversy that surrounded Polish director Andrzej Wajda’s feature film, Korczak (dir. Andrzej Wajda, Poland, 1990). Korczak is based on the life of Polish-Jewish pediatrician, writer, and educator Janusz Korczak, who devoted his life to children. He took care of two hundred orphans in the Warsaw ghetto and did not abandon them till the horrific end: they were all gassed at the Nazi death camp Treblinka in 1942. The film’s controversy has to do with the finale, which shows Korczak and the children in the transport train on its way to the camp. The train stops amid the fields, and in the intensely white fog, in slow motion, they all leave the car, disappearing into whiteness. While it is possible to interpret this moment as a metaphorical rendition of their death, the ending has been read by critics -- Claude Lanzmann, the director of Shoah (US, 1985), was the leading voice in the ensuing debates -- as a distortion of the truth that potentially expresses hope, deemphasizing the demise of Korczak and the children in the gas chamber. At stake seems to be the thorny issue of verisimilitude (the fact that the ending strayed from the literal) and hermeneutical possibilities for viewers. Weiwei’s case is more about the difference between commemoration and appropriation. But, I need to ask, is it possible to offer ethically conscious commemorative art without at least brushing against appropriation?

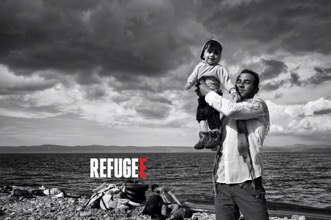

While pondering Weiwei’s image and the stormy controversy that ensued, I attended the “Refugee” exhibition currently on display at The Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles. [8] One of the main images promoting the exhibition is Tom Stoddart’s photograph of a father holding his child in his arms, up high, their bodies positioned against a calm sea and a cloudy sky. The caption reads: “A father celebrates with his child on the Greek island of Lesbos after a stormy crossing with his family over the Aegean Sea from Turkey” (Figure 2) The child has a slight smile, and, because of his placement against the sky – as if he were caught by his father mid-air -- he draws the spectatorial gaze. It is hard not to consider this photograph in the context of Aylan Kurdi’s image and its reenactment by Weiwei. One could see Stoddart’s photograph as both in alignment with, and in direct opposition to, Kurdi’s: both images feature boys of approximately the same age, both are documentary in nature, both signify perilous struggles of refugees. But, while one is about demise, the other offers hope and a “celebration.” It is the celebratory tonality of Stoddart’s photograph that might feel unsettling to some if read in the context of the image of Kurdi. Indeed, Stoddart’s image feels posed, as if performed for the Western gaze which would like to imagine the arrival as triumphal.

Figure 2. Tom Stoddart, A father celebrates with his child on the Greek island of Lesbos after a stormy crossing with his family over the Aegean sea from Turkey.

In Alison Klayman’s documentary about Weiwei’s artistic practice and political engagements, Ai Weiwei Never Sorry (2012), filmmaker Gu Changwei makes this point with reference to Weiwei: “Artists can easily offend others,” and curator Karen Smith adds, “There are particular moments which allow a voice to change the way the people think.” Benjamin Hunter, another voice critically commenting on Weiwei’s image, and perceiving him as “an artist utilizing tragedy for crass self-promotion,” goes further to make a broader claim about art and the refugee crisis: “The ethics of art-making in a humanitarian disaster are complex, with the cult of ‘the artist’ often becoming messily entangled with their good intentions. Being in “the Jungle,” [referring to the camp at Calais] where volunteer hands are always needed, I wondered whether artists should be making art about the refugee crisis at all.” [9]

Opening 2

“Push, push borders away. Push borders, do it today.”

Pussy Riot, “Refugees In”

In many ways Hunter’s question does not need to be answered since various artists have already produced work directly responding to the refugee crisis. Rapper M.I.A., a Sri Lankan refugee who came to London at the age of nine with her mother, directed her own video, “Borders.” Pussy Riot, a Russian feminist band known for its many provocative performances critical of Vladimir Putin’s government, in September 2015 participated in Banksy’s Dismaland theme park, contributing their powerful song, “Refugees In.” Complementing Banksy’s own efforts to counter xenophobic responses to the Syrian refugee crisis in Europe—most notably his drawing of Steve Jobs as a son of a Syrian migrant on a wall of the Calais “Jungle” —Pussy Riot called for open borders. Nadya Tolokonnikova, a Pussy Riot member, writes: “If we really are living in a global society, where is the free movement of people?” [10]

The video performance of “Refugees In” features three members of Pussy Riot locked up in a cage (“Cage me in, cage me out”), signaling the tropes of imprisonment, immobility, and enclosure, and reminding the viewers of the band’s own imprisonment in Russia for their oppositional artistic performances (Figure 3). The mise-en-scène of the video is murky and dark, underscoring perhaps the issue of legibility and (in)visibility vis-à-vis migrant lives. In it, there are many scenes showing violent confrontations with heavily armed police; the images are shaky, chaotic, and disorienting, punctuated by provocative lyrics: “Refugees in, Nazis out, governments here, should feel the shame, fucking liars, you’re to blame…Bombing people out of homes…We want peace, not fucking drones.”

By contrast, the visual rhetoric of “Borders” offers many images of vast, open spaces. In “Borders” M.I.A. herself focalizes the images. Placing herself centrally in most of the scenes (Figure 4), she sings: “Borders: What’s up with that?,” “Politics: What’s up with that?,” “Police shots: what’s up with that?,” “Identities: What’s up with that?,” “Your privilege: What’s up with that?,” “Broke people: what’s up with that?,” “Boat people: what’s up with that?” The mise-en-scène of the video is highly aestheticized and symmetrically orchestrated, featuring imagery associated with refugees’ perilous journeys: barbed wire, fences, deserts, boats, thermal blankets, and masses of dark-skinned men. Interestingly, there are no women or children. The fact that M.I.A. chooses to engage only men is telling: while images of women and children may evoke feelings of empathy in the context of humanitarian crises, men more readily meet anti-migrant sentiments being often stereotyped as potential criminals or terrorists and, overall, threatening bodies.

Figure 4. M.I.A., "Borders."

It would not be an exaggeration to state that the discourse in many countries surrounding the current refugee crisis ranges from benevolence to outright rejection of the possibility of housing refugees. Inflammatory anti-immigrant speech has been employed across Europe by politicians who, under the banner of national security, would ban refugees. The new ultra-conservative government in Poland, which came to power in the fall 2015 (and I offer this example as I have been following it most closely), was supported by a wave of xenophobic and nationalistic feelings. At stake was the preservation of the Catholic make-up of the nation, understood as the pure spirit of Polishness. Perusing surveys conducted by Polish TV, I have found that randomly selected Poles, approached in the streets, articulated two points in support of a selective acceptance of Syrian refugees: they need to be Christian and they need to come as families. Single men are not welcome. [11] Obviously not only in the Polish context, it is the figure of a dark-skinned man that becomes a repository of national anxieties and fears, propelled by what Homi Bhabha once called a “daemonic repetition.” Such daemonic repetitions fix stereotypes of dark-skinned men. For Bhabha the stereotype is a “form of knowledge and identification that vacillates between what is already ‘in place,’ already known, and something that must be anxiously repeated.” [12] It is through anxious repetitions that the stereotype is kept immobile, frozen in time.

We might read “Borders” as responding to such demonizations, countering them with a landscape inhabited only by dark-skinned men. We see these men walking, running, climbing fences, sitting on rocks wrapped in thermal blankets, and, in one sequence, forming a boat built out of their bodies, draped in sand-colored robes (Figure 5). We see them standing and sitting in moving boats, we see them lying inside the boats. While the initial shots of men are long takes which do not allow us to see them up close, in later parts of the video the camera stays close to their bodies, showing the viewers their faces. The movement from distance to proximity feels deliberate: it offers a direct confrontation with the men’s faces that, for the most part, appear expressionless and look away. Their gaze does not address the viewers directly, as if pushing away the voyeurism of racist spectatorship.

“Borders,” just like Weiwei’s performance, received its share of critical comments. Tom Murphy, for example, writes: “Critics say that M.I.A. used people of color as props for her art. And there are of course those who disagree with her ideas about how to treat refugees. All of which fit into the ultimate goal of the song and video – to spark debate and reflection on a real world issue.” [13]

Figure 5. M.I.A. "Borders."

Who May Speak? And Make Art?

In fall 2015, Tania Canas, Arts Director of RISE—Refugees, Survivors, and Ex-detainees—an Australian organization whose motto is “Nothing about us without us,” on the RISE website, issued a declaration titled “10 Things You Need to Consider If You are an Artist—Not of the Refugee and Asylum Seeker Community—Looking to Work with Our Community.” [14] She opens with the following statement: “There has been a huge influx of artists approaching us in order to find participants for their next project. The artist often claims to want to show ‘the human side of the story’ through a false sense of neutrality and limited understanding of their own bias, privilege and frameworks.” In what follows, Canas speaks against careless utilization, exploitation, and homogenization of refugee communities. She cautions about using the refugee community as a playground for western humanitarian benevolence. She calls on artists to interrogate their intentions and potential modes of participation, and to realize their privilege. She writes: “We are not a resource to feed into your next artistic project…Our struggle is not an opportunity, or our bodies’ a currency, by which to build your career,” and “Your demands on our community sharing our stories may be just as easily disempowering.”

Reading the tone of Canas’s manifesto closely, one can deduce that it must have been generated by an overwhelming sense of frustration and a desire to be protective of the refugee community, with its varied stories and experiences. It is imperative to keep Canas’s stipulations in mind, especially when refugees’ bodies are mobilized to feed “hungry Western eyes,” as Slavoj Žižek observed in the context of the Balkan wars. [15] There are eyes that are eager to see, whether they see sensationalized images of suffering, or celebratory images of human endurance. It is hard, no doubt, to produce art that self-consciously seeks to resist the aesthetization and sublimation of what Imogen Tyler calls “social abjection”: “abjection as a lived social process.” [16]

But one has to wonder why Canas automatically assumes that, if one is a part of “the Refugee and Asylum Seeker Community,” one might be excluded from following her stipulations. The unspoken presupposition is that if an artist is a refugee herself, she will instinctively “know” how to produce art ethically. This assumption exemplifies the vexing logic of authenticity and authority and a stale identity politics. Perhaps this is the type of thinking that allows critics to be forgiving toward M.I.A.’s “Borders” (because she came to the UK as a refugee) while aggressively attacking Weiwei (who, even though having a contentious relation with the Chinese government, is not a refugee)? In this context, I remember Krista Ratcliffe’s pedagogical point that “lived experience does not guarantee knowledge” and, while experience certainly offers certain epistemological advantages, it cannot guarantee the creation of art that would, without potential violations, honor the multitude of refugee experiences. [17] Such insistence on authenticity, supposedly securing authority and veracity, also shuts down many potentially critical voices and misses the point that art is messy. Art cannot easily follow, let alone enforce, biological, national, or experiential border lines.

Tolokonnikova acknowledges that “Refugees In” is politically charged and unapologetic for its strong lyrics: "We are planning to release a lot of disturbing videos next year. We hope that you will not like them."[18] In their strong address, both “Refugees In” and “Borders” manifest their content overtly. By contrast, Weiwei’s reenactment is more ambiguous and thus unnerving. Not only does it offer a “certain poetic space,” as he says, for the contemplation of the mournability of lives that may or may not be perceived as worthy of grieving, but it strays from the aestheticization or sublimation of trauma. If this is how we read it, we can then also perceive a treacherous sentimentality in Stoddart’s photograph, which currently graces banners throughout Los Angeles, announcing the “Refugee” exhibition.

Notes

[1]Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator, trans. G. Elliott (London: Verso, 2009), 83.

[2]Rama Lakshmi, “Chinese Artist Ai Weiwei Poses as a Drowned Syrian Refugee Toddler,” The Washington Post, Jan. 30, 2016.

[3]Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (London: Verso, 2009).

[4]Ryan Steadman, “Ai Weiwei Receives Backlash for Mimicking Image of Drowned 3-Year-Old Refugee,” Observer Culture, Feb. 1, 2016. http://observer.com/2016/02/photo-of-ai-weiwei-aping-drowned-refugee-toddler-draws-praise-ire/.

[5]Niru Ratnam, “Ai Weiwei’s Aylan Kurdi Image is Crude, Thoughtless, and Egotistical,” The Spectator, Feb.1, 2016. http://blogs.spectator.co.uk/2016/02/ai-weiweis-aylan-kurdi-image-is-crude-thoughtless-and-egotistical/.

[6]Maurice Stierl, “Contestations in Death: the Role of Grief in Migration Struggles,” Citizenship Studies 20 (2) (2016): 174.

[7]Stierl, “Contestations,” 173.

[8]The Refugee Exhibition, April 23- August 21, 2016, Annenberg Space for Photography, Los Angeles.

[9]Benjamin Hunter, “What Can Art Offer the Refugee Crisis?” Canadian Art, Feb.1, 2016, http://canadianart.ca/features/art-at-the-end-of-the-road/.

[10]Nadya Tolokonnikova, “’Dismantle Europe’s Borders’: Pussy Riot Speak Up for Refugees,” The Guardian, Nov. 18, 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/nov/18/pussy-riot-refugees-video-europe-borders.

[11]See “Imigranci z Syrii zagrożeniem dla Polaków? Sonda” (“Syrian Immigrants –a Threat for Poles? A Pole”), Sept. 11, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZZenVb0fwq8.

[12]Homi Bhabha, “The ‘Other’ Question,” Screen 24 (6) (1983): 18.

[13]Tom Murphy, “Refugee Crisis: M.I.A.’s Powerful Protest Song and Video,” Humanosphere, Dec. 29, 2015. http://www.humanosphere.org/basics/2015/12/refugee-crisis-m-s-powerful-song-video/.

[14]Tania Canas, “10 Things You Need to Consider If You are an Artist – Not of the Refugee and Asylum Seeker Community – Looking to Work with Our Community,” Oct. 5, 2015. http://riserefugee.org/10-things-you-need-to-consider-if-you-are-an-artist-not-of-the-refugee-and-asylum-seeker-community-looking-to-work-with-our-community/.

[15]Slavoj Žižek, The Metastases of Enjoyment: Six Essays on Woman and Causality (London: Verso, 1994), 2.

[16]Imogen Tyler, Revolting Subjects: Social Abjection and Resistance in Neoliberal Britain (London: Zed Books, 2013), 4.

[17]Krista Ratcliffe, Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), 140.

[18]Richard Bienstock, “Watch Pussy Riot Perform at Banksy’s Dismaland for ‘Refugees In’ Video,” Rolling Stone, Nov. 18, 2015.

Katarzyna Marciniak, Professor of Transnational Studies in the English Department at Ohio University, specializes in the discourses of immigration and foreignness. As Research Fellow, she is affiliated with the Department of English Studies, University of South Africa. She is the author of Alienhood: Citizenship, Exile, and the Logic of Difference (University of Minnesota Press, 2006) and Streets of Crocodiles: Photography, Media, and Postsocialist Landscapes in Poland (Intellect/University of Chicago Press, 2010), co-editor of Transnational Feminism in Film and Media (Palgrave, 2007), Protesting Citizenship: Migrant Activisms (Routledge, 2014), Immigrant Protest: Politics, Aesthetics, and Everyday Dissent (SUNY Press, 2014), and Teaching Transnational Cinema: Politics and Pedagogy (Routledge, 2016). She also co-edited a special issue of Feminist Media Studies on “Transcultural Mediations and Transnational Politics of Difference” (2009), and a special issue on “Immigrant Protest” for Citizenship Studies (2013). She is Series Editor of Global Cinema, a new book series from Palgrave, and the winner of the 2010 Florence Howe Award for Outstanding Feminist Scholarship for her essay "Pedagogy of Anxiety" published in Signs.