The Street is in Play: A Reading of Banksy's Better Out Than In

Tuesday, June 3, 2014 at 6:35PM

Tuesday, June 3, 2014 at 6:35PM Andrea Zeffiro

[ PDF Version ]

On 1 October 2013, social media was abuzz with postings that Banksy, the elusive and anonymous street artist,[1] had created a new work in Manhattan. Less than twenty four hours later, Banksy confirmed the rumour, and announced via the now defunct banksyny.com his self–appointed month–long artist residency on the streets of New York, aptly titled Better Out Than In. Like so many others, I found myself tracking Banksy’s daily happenings – albeit virtually – as well as the public responses the works elicited. What became apparent, and quickly, was how Banksy persuaded a myriad of individuals - the inhabitants of and visitors to New York, his followers and fans, and finally, digital bystanders like myself – into a public dialog. The focal point of this dialog was, first and foremost, New York City. Banksy employed the city as his proverbial canvass, and in this sense, the city became his playground. But if one were to delve deeper, beyond the literal use of New York City, toward its symbolic significance – and indeed, enduring myth – as a capital of progressive public culture, then the dialog put forth by Banksy in Better Out Than In isn’t just about New York, rather, it speaks to the precarity of public culture within contemporary city spaces under global capitalism.

Public Culture

In this essay, public culture is informed by and contextualized through three theoretical and conceptual antecedents: the public sphere, counterpublics, and global cultural forms. In Habermas’s public sphere, communicative action is a key characteristic in the sustenance of a diverse and democratic culture. The public seeks to reach mutual understanding and to coordinate action though open discussion and debate.[2] Yet the public, as theorized by Habermas, is unable to account for what Michael Warner[3] describes as the transient participants in common publics. A master public does not exist. This public is a practical fiction, a kind of social imaginary and ideology.[4] In its place are a multiplicity of discourses and publics, and any one public comes into existence through the circulation of common texts, and the reflexive circulation of discourse.[5] The subjects that constitute a public, rather than function as the cause of its discourse, are an effect of it:[6] they become interpellated to a community, a set of ideas, desires, values and norms, and the way in which a public defines itself, despite engrained affinities, is a continuous struggle. A public, however, especially one that is bound to hegemonic structures and elite entities, may incite spontaneous opposition in the form of a counterpublic. Counterpublics, as Nancy Fraser explains, are "parallel discursive arenas where members of subordinated social groups invent and circulate counter-discourses to formulate oppositional interpretations of their identities, interests, and needs."[7] A counterpublic emerges in tension with a mainstream public, and equipped with new modes of expression – discursive, aesthetic, and affective – positions itself in contestation with the mainstream.

As a zone of debate where cultural forms and fields are confronted, questioned, and opposed in novel and unanticipated ways,[8] the arena of public culture enables a myriad of communities – publics and counterpublics – to define and disseminate competing discourses. "Public culture" signifies the signs symbols, languages and codes[9] – those modes of expression communicated and experienced publically – that provoke debate, forge identities, and voice concerns.[10] Framing Banksy’s residency as an engagement and expression of public culture opens it towards an examination of the ways in which cultural producers might implement media, artistic and popular cultural forms, and modes of performance as rhetorical tactics to influence publics and public consciousness. It is necessary, however, to contextualize the paradox of public culture under globalization, specifically, the manner in which cultural forms transcend nation-state borders, and yet as vehicles of cultural significance and group identities, these forms continue to express the cultural, economic, social and political nuances of a locality.[11] Public culture, and indeed Banksy’s work, is localized and site-specific, but it is also taken up far and beyond the constituency of one location, and increasingly, one communicative platform.

#BanksyNY

Banksy’s oeuvre spans stencil graffiti, orchestrated pranks, site-specific installations, and more recently, documentary film, all of which are laden with political and social commentaries and critique, dispelled through humour and satire. Some of Banksy’s better known works include a series of images on the Israeli West Bank wall, an inflatable Guantanamo Bay prisoner doll at Disneyland, subverted artworks placed in prominent museums in the United States and Britain, and large-scale graphic works for the 2012 summer Olympics in London. The artist has consistently chosen locations for politically motivated reasons. In 2008 for example, Banksy produced a number of pieces in New Orleans that coincided with the third anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, and the series highlighted the stagnant efforts toward rebuilding the city, both physically and spiritually. It was also an occasion for Banksy to take on the Grey Ghost, the pseudonym given to Fred Radtke, the New Orleans resident and anti-street-art crusader known for buffing any and all forms of graffiti with his signature splotches of gray paint.

Following a year of relative inactivity, Banksy returned to publicness in New York. As a public event, however, the residency had reach beyond the parameters of a geographical area, thanks in part to the circulation of content via Banksy’s website, Instagram account,[12] and YouTube[13] channel. For thirty-one days Banksy placed works throughout New York’s five boroughs, and each day,[14] the artist methodically posted a photo or video of a new work online with minimal details as to the location. A treasure hunt ensued, as enthusiasts, using Banksy’s visual evidence along with their knowledge of the city, sought out the various works, and more often than not, publically documented their encounters through social media. A web search of the hashtag #BanksyNY, for instance, reveals the extent to which Banksy’s activities were documented and debated.

From an archival perspective, documentation through social media facilitated a public archiving of the residency, which is consequential given the impermanence of street art. More specifically, these digital traces express a crossing of borders between media, that is, between public space and social media, and exemplify intermediality in a broad sense.[15] The term, "intermediality," alludes to the interconnectedness[16] of and the complex set of relations between media,[17] and it confronts the ways in which combinations, transformations and references between media might influence the interpretation of cultural works.[18] In regards to Better Out Than In, intermediality marked the actions taking place between public space and social media. The reproduction and circulation of Banksy’s works online and through social networks, as a means of expression and exchange, reiterate how public space and social media are constituents of a wider cultural environment.[19]

Banksy’s efforts to engage virtual or networked publics underscore the consequential role of public space in the cultivation of public culture. Public space pertains to the real and lived spaces – those physical spaces in the real world – but it also refers to those virtual public spaces – the immaterial spaces that are encountered through networked technologies. Digital technologies and intermedial border-crossings[20] can extend the capacity for publics and counterpublics to nurture and circulate competing discourses.[21]

Graffiti is a Crime. Sometimes.

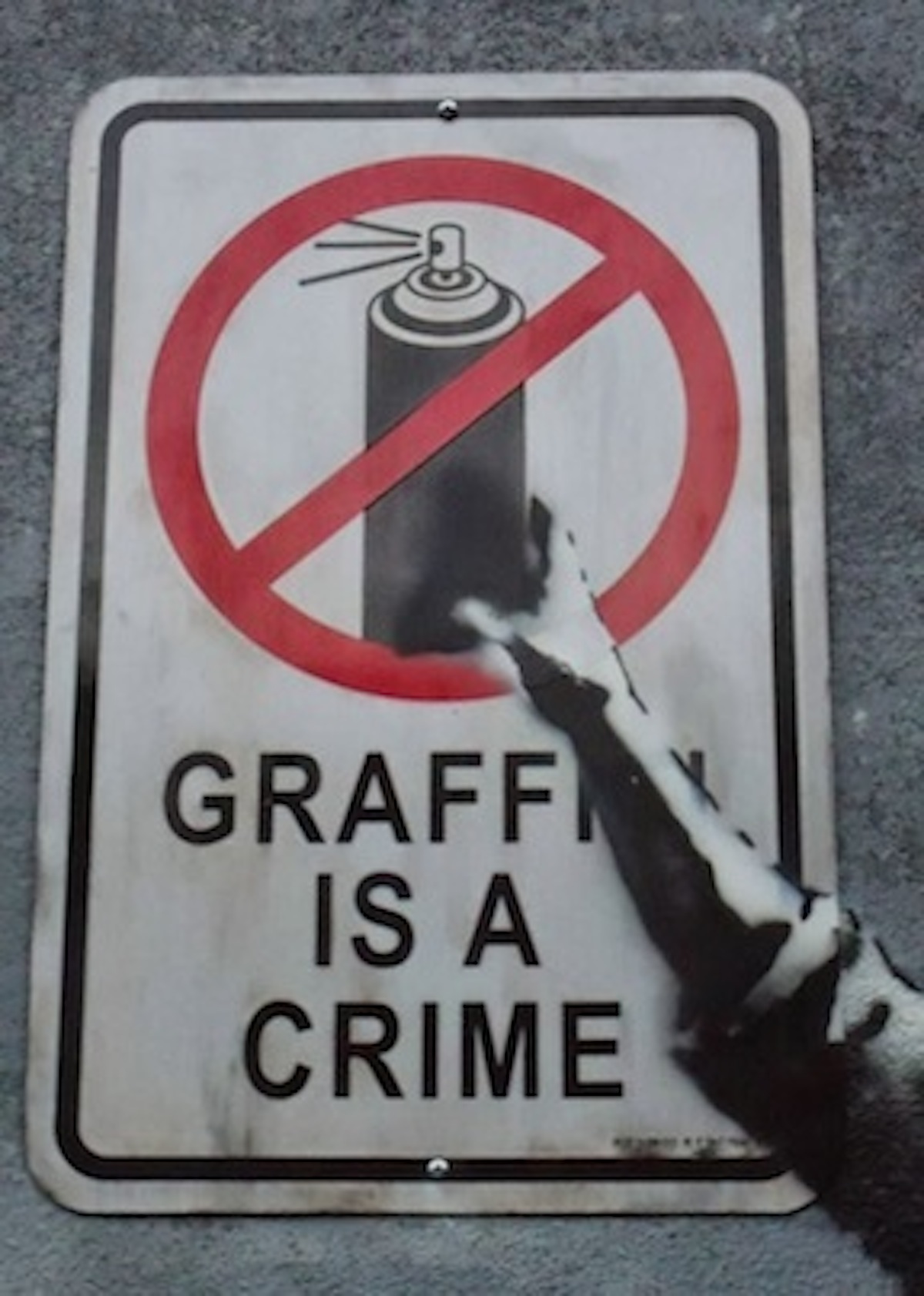

Banksy’s first work in the residency, The Street is in Play, depicts two boys dressed in overalls and flat caps with one of the boys standing on the back of the other and reaching for a can of spray paint in a "Graffiti Is A Crime" sign. Beside the piece is a stenciled 1– 800 number for an audio guide, which mimics both in style and substance the depthless rhetoric that is common to audio guides accompanying institutionalized cultural artifacts. However, unlike traditional audio guides, the narrator provokes the viewer and asks: "What exactly is the artist trying to say here?" Instead of providing a response, the narrator commands: "you decide. Really. Please do. I have no idea." The onus for meaning making as the narrator suggests, is with the viewer.

Less than 24 hours after the unveiling of The Street is in Play, the Smart Graffiti Crew – a crew from Queens – entered into a public conversation with Banksy by altering his work as a critical commentary on the ways in which certain street art works are more revered than others. A reading of the altered piece, in which the Smart Graffiti Crew added their logo in the place of the can of spray paint,[22] reconfigures Banksy’s original piece, which depicted the condemnation of street art in general, to a denunciation of the Smart Graffiti Crew specifically. The new sign proposes that work produced by the Smart Graffiti Crew is reprimandable, which is to say not all street art and certainly not Banksy’s work. The modified sign therefore intimates the ways in which the institutionalization and comodification of street art culture, in addition to the sways of the market, have enabled one artist to "bank" on their work, while another artist’s work is met with indifference.

The "bombing" on 3 October 2013 of Banksy’s midtown Manhattan Fire Hydrant piece – the work depicts a dog urinating on a fire hydrant, which the audio accompaniment describes as "spray art" – appears at first glance to be one tagger’s venture at leaving their mark on a Banksy piece. Within New York’s graffiti scene however, the tag "RD" is attributed to RD, a bombing legend whose two-letter tag was a ubiquitous mark in the city during the 1980s and 1990s, and within the last few years, "RD" has appeared on fire hydrants throughout New York.[23] In Banksy’s piece, RD tagged only the fire hydrant, and in doing so, completed the street scene, so to speak. Reinterpreting Banksy’s piece with "RD" tagged on the fire hydrant, dissolves the first reading of "dog urinating on a fire hydrant", and transforms it into "dog urinating on a fire hydrant tagged by RD", hence, "a fire hydrant in New York". One can read the tagging of the fire hydrant as a means through which RD lends credibility to Banksy’s project within the hierarchy of New York’s street art communities.

When the Smart Graffiti Crew and RD entered into dialogue with Banksy, their respective modifications to residency works engendered critical discourses that articulated the paradoxical position Banksy occupies between the competing realms of street art and institutionalized art. The modifications carried out by the Smart Graffiti Crew and RD can be read as acts of reterritorialization, as a means of differentiation from Banksy. Positioning their work in contrastive relation to Banksy’s work is a mode of renegotiating the terrain of street art. If Banksy embodies a mainstream street art discourse, then the Smart Graffiti Crew and RD are employing modes of transformative address to distinguish and perhaps counter-position themselves from the realm of mainstream street art.

Banksy reached out to New York’s street art community when he unveiled a three–dimensional floating bubble "Banksy" tag as his final piece of the residency. The text accompanying the photo-documentation on the website read: "And that's it. Thanks for your patience. It's been fun. Save 5pointz. Bye." The piece was placed a few blocks from 5 Pointz: The Institute of Higher Burnin', the sprawling block of warehouses on Jackson Avenue in Long Island City, Queens. 5 Pointz is a street art mecca.[24] Over a twelve–year period, 1,500 international artists have left works on the exterior of the five story buildings. In conventional terms, 5 Pointz is a street art museum, validated by the busloads of tourists that routinely visit the three–acre site. Its owners however, want to replace the warehouses with two glass towers and 1,000 new luxury apartments in what The New York Times has reported to be a $400 million development project.[25] The collective responsible for the handling of 5 Pointz sought out a temporary restraining order under the 1990 Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), which grants artists certain moral rights over their work, regardless of who owns it. When Brooklyn federal court Judge Frederic Block denied the injunction, the collective planned to file with the Landmarks Preservation Commission in attempt to have the site deemed an official historic landmark.[26] In the early hours of 19 November 2013, 5 Pointz was whitewashed: the exterior walls painted in white paint, thereby erasing an entire history of (street) art.[27] The lease of the artists’ space ended as of 2 December 2013, and demolition will begin in the next few months.

Initiatives for urban renewal – as it is often called – extend beyond whitewashing. In present day New York – like many other contemporary urban centres – landowners are enticed by tax incentives and other "public" programs that make it far more lucrative to redevelop existing properties than restore them. "The world we live in today," explains the narrator in the audio accompaniment to Banksy’s final piece, "is run – visually at least – by traffic signs, billboards and planning committees. Is that it? Don’t we want to live in a world made of art, not just decorated by it?" In as much as the final piece is an ode to street art, the lamentation, I argue, is also aimed at what Henri Lefebvre refers to as, "the right to the city,"[28] or more specifically, the right to participate in the formation of public spaces, and therefore, public culture. This is not to imply that public culture or an idealized version of it has perished. Public culture, as I previously described, is a "contested terrain"[29] and is constantly in need of being produced, reproduced and reimagined. That said, the manner in which public space continues to be largely defined and enclosed by commercial space, has a definitive impact on the ways in which publics and counterpublics are able to articulate their lived experiences. If "the question concerning public culture," as Dustin Kidd[30] reflects, "is a democratic question,"[31] then Banksy’s residency, as an engagement and expression of public culture, was an occasion to provoke debate and demonstrate the ways in which social life can be constructed in ways that differ from dominant conceptions of reality. In this sense, public culture – in all of its manifestations – is better out (i.e. in the public domain) than in (i.e. contained, owned, regulated).

Notes

[1] Banksy’s body of work is referred to here as ‘street art’ because it spans stencil graffiti, orchestrated pranks, and site-specific installations. Moreover, ‘street art’ serves as an umbrella term for forms of artistic expression that are produced in public locations and often outside of official arts or cultural institutions.

[2] Jürgen Habermas, Reason and the Rationalization of Society, vol.1 of The Theory of Communicative Action, trans. Thomas McCarthy (Boston: Beacon Press, 1984), 86.

[3] Michael Warner, Publics and Counterpublics (New York: Zone Books, 2002).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 11.

[6] Mary Kupiec Canton, “What is public culture? Agency and Contested Meaning in American Culture- An Introduction,” in Public Culture: Diversity, Democracy, and Community in the United States, ed. Marguerite S. Shaffer (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 14.

[7] Nancy Fraser, “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy,” in Habermas and the Public Sphere, ed. Craig Calhoun (Boston: MIT Press, 1992), 123.

[8] Arjun Appadurai and Carol A. Breckenridge, “Why public culture?” Public Culture, 1 (1988): 6.

[9] Mary Kupiec Canton, “What is public culture?” in Public Culture, ed. Shaffer (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 14.

[10] Dustin Kidd, "Public Culture in America: A Review of Cultural Policy Debates," The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 42, no. 1 (2012): 11-21.

[11] Appadurai & Breckenridge, “Why public culture?” Public Culture, 1 (1988): 6.

[12] See: http://instagram.com/banksyny#

[13] See: http://www.youtube.com/channel/HYPERLINK "http://www.youtube.com/channel/UC9fiHm54bmH9LWBbjBJGOFg" UC9fiHm54bmH9LWBbjBJGOFg

[14] Banksy executed all but one of the planned works. The 23 October 2013 post on his blog read: “Today’s art has been cancelled due to police activity.”

[15] Irina O. Rajewsky, “Intermediality, Intertextuality and Remediation: A Literary Perspective on Intermediality,” Intermédialités: Histoire et Théorie des Arts, des Lettres et des Techniques 6 (2005): 43-64.

[16] Klaus Bruhn Jensen,“Intermediality,” in International Encyclopedia of Communication, ed. Wolfgang Donsbach (Malden, MA: Blackwell Science Ltd, 2008) 2385-2387.

[17] Lars Elleström, “The Modalities of Media: A Model for Understanding Intermedial Relations,” in Media Borders, Multimodality and Intermediality, ed. Lars Elleström (Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2010) 11-50.

[18] Leena Eilittä, “Introduction: From Interdisciplinarity to Intermediality,” in Intermedial Arts: Disrupting, Remembering and Transforming Media Edited, ed. Leena Eilittä, Liliane Louvel and Sabine Kim (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012) viii.

[19] Jensen,“Intermediality,” in International Encyclopedia of Communication, ed. Donsbach (Malden, MA: Blackwell Science Ltd, 2008) 2385-2387

[20] Rajewsky, “Intermediality, Intertextuality and Remediation” in Intermédialités 6 (2005): 44

[21] Numerous media and communication scholars have examined the interconnections between the Internet, social media and the public sphere: Yochai Benker, The Wealth of Networks (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006); Jean Burgess and Joshua Green, YouTube (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2009); Manuel Castells, Communication Power (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009); Zizi Papacharissi, “The Virtual Sphere 2.0. The Internet, the Public Sphere, and Beyond,” in Routledge Handbook of Internet Politics, ed. Andrew Chadwick and Philip N. Howard (New York: Routledge, 2009), 230-245; Christian Fuchs, Social Media: A Critical Introduction. (London: Sage, 2014).

[22] Image: http://www.animalnewyork.com/2013/smart-crew-swaps-out-banksys-graffiti-is-a-crime-sign-with-their-own/

[23] Bucky Turco, “Meta Graffiti: RD Tag on Banksy Fire Hydrant,”17 October, 2013, http://www.animalnewyork.com/2013/meta-graffiti-rd-tag-on-banksy-fire-hydrant/

[24] Robin Finn, “Writing’s on the Wall (Art Is, Too, for Now),” New York Times, 27 August 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/28/nyregion/5pointz-arts-center-and-its-graffiti-is-on-borrowed-time.html?pagewanted=all

[25] Cara Cuckley and Marc Santora, “Night Falls, and 5Pointz, a Graffiti Mecca, Is Whited Out in Queens,” New York Times, 19 November 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/20/nyregion/5pointz-a-graffiti-mecca-in-queens-is-wiped-clean-overnight.html?smid=pl-share

[26] John Marzulli, “Federal judge refuses to stop plan to demolish 5Pointz graffiti mecca in Long Island City,” New York Daily News, 12 November 2013, http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/queens/judge-refuses-block-5pointz-demolition-article-1.1514628

[27] Mostafa Heddaya, “5Pointz Whitewashed Overnight,” Hyperallergic, 19 November 2013, http://hyperallergic.com/94315/5pointz-whitewashed-overnight/ ; and Hrag Vartanian, “5Pointz: The Morning After,” Hyperallergic, 20 November 2013, http://hyperallergic.com/94553/5pointz-the-morning-after/

[28] Henri Lefebvre, Writings On Cities, trans. Elenore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1996), 158

[29] Appadurai & Breckenridge, 7

[30] Dustin Kidd, "Public Culture in America: A Review of Cultural Policy Debates," The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 42(1) (2012): 11-21

[31] Ibid., 18

Andrea Ziffiro is an Adjunct Professor in the Department of Communication, Popular Culture and Film, Brock University. For more: www.andreazeffiro.com