A Business without a Future? The Parisian Vidéo-Club, Past and Present

by Brian R. Jacobson and Joshua Neves

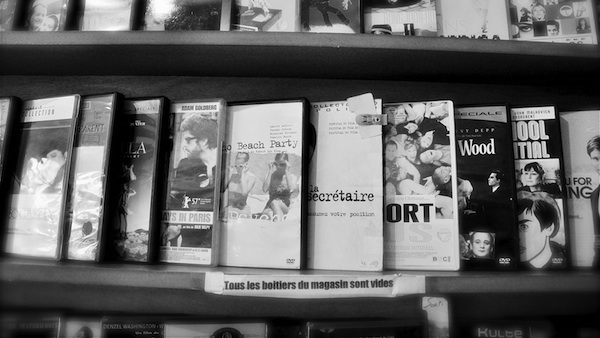

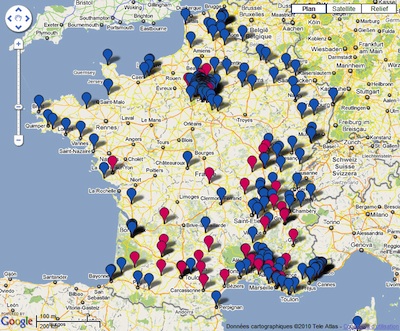

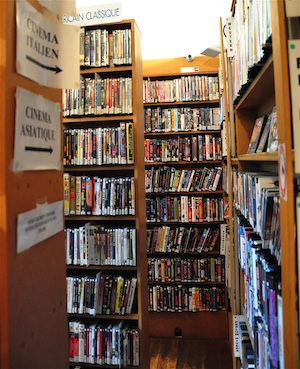

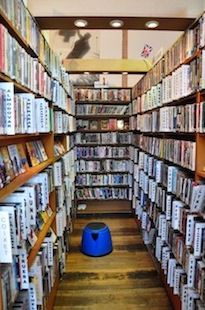

[ PDF version ] Almost eighty-five years after the cinématographe created a flurry of enthusiasm for cinema on the Grands Boulevards, Paris’s first video rental stores were met with no less excitement or skepticism by their first owners, clients, and industry critics. Despite early predictions of the video business’s certain failure that evoked Antoine Lumière’s apocryphal dismissal of cinema’s future, thirty years later French vidéo-clubs remain an important if increasingly marginalized form of media distribution in the nation’s capital. Compared with similar markets, the history of French video stores offers a familiar tale of initial enthusiasm and success, followed by periodic cycles of modest growth, rapid decline, and often-failing efforts to form a business model capable of adapting to technological changes and new consumption practices. Using a combination of historiographic research and on-site analysis and interviews,[i] this essay examines historical and ongoing developments in video rental in France, with particular attention to current trends in Paris. Our historical and field research shows that the French context is at once particular—marked by French legal and economic strategies (l’exception culturelle française), consumers’ attitudes towards media technologies, and stereotypes of French cinephilia—and at the same time surprisingly continuous with the broader landscape of media change in places like the United States and Australia. Indeed, the case of French vidéo-clubs offers important evidence of how local and national actors both reproduce and reshape emerging global media practices in ways that nonetheless reflect historical traditions and cultural specificity. A Brief History of the Vidéo-Club in France Video rental stores—or vidéo-clubs in French—began to appear rapidly in the early 1980s with rising consumer adoption of the VCR (magnétoscope) and the increasing availability of prerecorded videocassettes. Encouraged by positive industry predictions for growth in the VCR market and reports of intense consumer demand, investors and cinephiles opened approximately four thousand stores between 1980 and 1982.[ii] Trade journals such as Audio Vidéo Magazine celebrated the success of the young industry by inviting readers to learn “How One Becomes a Vidéomaniaque?” and announcing “The Explosion of the Video Market.”[iii] Such articles offered tales of profit-boosting rental addicts and fêted the video business as a “cheerful” respite from a period of general economic gloom. Amidst this early positive outlook, however, even the most optimistic and successful industry professionals advised caution to those considering video store ownership. Franchise proprietors reminded investors that the video store market promised to fluctuate for perhaps several years to come, and an article otherwise celebrating video rental (“Vive la location!”) noted that stores continued to “fumble” in search of stability.[iv] Other observers more bluntly predicted the market’s imminent demise. In the same 1982 Cahiers du Cinéma article that announced the videotape’s “arrival,” for instance, Serge Le Péron reported that already “rumor in the profession judges that 30 to 40 percent of existing video stores will very quickly go bankrupt.”[v] Such dire assessments accurately reflected the difficulties faced by many early video stores. Problems not only included unsustainably low rental prices, generally poor business practices, and piracy (in the form of cassette copying by both consumers and video stores themselves), but also government regulations that slowed the growth of the VCR and videocassette markets.[vi] These regulations—announced in April and October 1982, respectively—included an annual 600 Franc licensing fee for VCR owners (approximately $100 in 1983) and a required lag time of eighteen months from theatrical to video release.[vii] The introduction of the license fee placed video in a long tradition—dating to radio in the early 1930s—of French media laws aimed at routing profits from media consumption back into French broadcasting and production. Despite rising protests from various sectors of the video trade, French officials dealt the industry a further blow in November 1982 when they ordered all VCR imports to be rerouted through Poitiers, one of the smallest customs houses in France. This measure, an often-cited case of protectionist economic policy, was intended to curb the rapid import of popular Japanese brands and boost the struggling European V2000 video format. Audio Vidéo Magazine’s editors described the policy as “hypocritical, absurd, and dangerous” and noted that it was causing “panic” in the market as importers and distributors faced dwindling VCR stocks and increased operating costs that threatened to derail the market.[viii] Indeed, in an early study of the video store Catherine Dupin noted that, due in part to these regulations, by 1985 France was “well behind” in the VCR market, and by 1989 it had one of the lowest rates of market penetration in Europe.[ix] For video stores, the slow VCR market represented only one in a growing series of threats to a business model that had yet to even fully form.[x] Perhaps the biggest and, ultimately, most long-term challenge appeared in 1984 when France launched its fourth (and first private) television network. The new channel, Canal+ (aka Canal Plus), specialized in recent international cinema and sports broadcasting for paying subscribers. Two more channels—La Cinq and TV6—followed in 1986, further eroding the video store’s increasingly tenuous consumer market.[xi] By 1986 the number of video rental stores in France had already dropped to about 2,500 (with about 250 in Paris).[xii] Owners of Parisian stores surveyed that year painted a bleak picture of the video store’s immediate future. Hampered by television (especially Canal Plus’s movie programming), France’s stunted VCR market, dampened public interest in video, and over-saturation of the rental market, 80 percent of owners estimated that their business was “no longer profitable under the present market conditions.”[xiii] Within five years only 1,200 rental stores remained in France, despite a general expansion of the video market in the early 1990s.[xiv] Thanks to the government’s repeal of VCR license fees beginning in 1987, falling videocassette prices, and a rapidly increasing supply of Hollywood studio releases on video, profits in France from video slowly began to outpace theatrical sales.[xv] These gains, however, developed out of a dramatic shift away from rental, leaving video stores with seemingly little choice but to develop new strategies or close.[xvi] The automated video rental machine emerged from this moment of crisis as a new and lasting form of distribution that contributed to a renewal of the rental market in France. In 1995 the company Cinemat France installed its first Cinebank machines, followed by automated systems from Direct Video in 1996, Derby in 1997, France Distributeur Automatique in 1999, Golden Video in 2000, and Rush Diffusion in 2001.[xvii] Although video sales continued to dominate rental, beginning in 1996 the rental market outpaced sales growth, which dropped steadily through the remainder of the 1990s.[xviii] Fueled by automated distribution and the emergence of chains such as Video Futur that combined in-store rental with automatic machines, the VHS rental market continued to grow for the rest of the decade. Although the emergence of the DVD slowly halted VHS growth (in 1999 DVD rentals in France surpassed VHS for the first time), the rental market as a whole continued to grow into the new millennium.[xix] On the strength of the new DVD market, video rental rose to an all-time high in France in 2002, with an estimated 6,000 automated rental machines in service and a resurgence of video rental stores.[xx] Even with the downturn in rentals beginning in 2003, by 2004 France was home to an estimated 7,000 video rental sites.[xxi] But despite growth in DVD rentals that lasted into 2005, the near-collapse of the VHS market that year helped signal a new decline in the French rental market.[xxii] Once again, competition came largely from new television systems and forms of copying and unauthorized distribution. Video on Demand (VOD) launched in France in December 2003, first with FREE TV, followed quickly by TPSL from Télévision Par Satelite, France Télécom’s “Ma Ligne TV,” and Canal Plus’s “CanalSatDSL.”[xxiii] Although video renters benefited from a 2006 law delaying VOD release for six weeks following a film’s release on DVD (itself six months after theatrical release), video stores continued to suffer.[xxiv] The increased popularity of Internet downloading has contributed to those woes despite efforts by France and the European Union to bolster legal measures against online content distribution.[xxv] As a result, rental figures in France have fallen steadily from a high of around 60 million DVD rentals in 2005 to 36 million in 2007.[xxvi] For video stores the decline has been even more dramatic due to increasing competition from online rental companies such as Glowria that have bolstered the otherwise declining market.[xxvii] According to some estimates the number of video stores fell to 5,000 in 2006, 3,500 in 2008, and, finally, only 2,500 in 2010.[xxviii] In Paris, the video store’s decline has been felt by customers who find their local stores closed without warning and is marked by lingering traces of stores that no longer exist, such as the outworn sign for the former St. Maur Video shop in the eleventh arrondissement. Strategies for Survival: Consolidation, Automation, Specialization, and Interstitial Practices While the recent history of Parisian vidéo-clubs fits within larger trends of store closures, the rise of online distribution (including piracy), and digital television, the city’s enduring video store locations also offer site-specific insights into this transition. Clichés about French cinephilia aside, the landscape of Paris’s video stores, as described by shop owners and staff, runs parallel to contemporary developments in American and other Western markets. As elsewhere, many video stores have been forced to close and, in shrinking numbers, chain stores, local specialty outlets, and automated distribution are the city’s mainstays, accompanied by unregulated, illegal, and/or ephemeral forms of distribution that continue to emerge in the margins left by industry-sanctioned business practices. Consolidation The recent merger of Glowria, France’s Netflix, with dominant video store franchise Video Futur exemplifies current challenges and consolidations in the industry. Under the Video Futur brand, the union now combines Video Futur’s in-store locations and automated kiosks with Glowria’s market leading rent-by-mail and VOD services, suggesting the increasingly elastic space of contemporary video stores.[xxix] Video Futur’s online presence and physical stores materialize this condensation, linking residual and emergent rental practices under a single “Galaxy” membership, website, and neighborhood franchise location.[xxxi] Both video-futur.com and glowria.fr, which for the moment link to the same Video Futur interface, are divided into four main access points, highlighting users preferred forms of rental: downloading (téléchargement), flat-rate mail service (à domicile), store locations (nos magasins), and cinebank machines (distributeurs cinebank). This agglomeration, however, is very much in process, as indicated by the continued use of the Glowria name brand, the uneven integration of rental kiosks within stores (e.g., they tend to be operated by subcontractors), and inconsistent networking of franchise locations (e.g., in many cases customers can only return discs to the stores and kiosks where they originally rented them). The Video Futur store located on Rue Monge in the fifth arrondissement combines a simply organized chain-style storefront, emphasizing new releases and family titles up front, with a sidewalk kiosk, allowing members 24-hour access to discs. While our attempts to interview the staff and photograph the store were declined—the staff instead directed us to a recent press release in the free daily newspaper 20 minutes—figure 6, taken from the umbrella website, offers a sense of the chain’s modular layout. At present, it is too early to tell if Video Futur indeed offers a model for the convergent video stores of the future or, rather, is an attempt to split risk while reorganizing for a distribution market that is increasingly geared toward the controlled downloading and streaming of content onto household screens and mobile devices. Automation Part of a resurgence of video rental in the late 1990s, Cinebank machines have also continually adapted to keep up with market trends, video formats, and changing viewing technologies. In 2007, Video Business reported that the Cinebank movie rental service, one of three retail brands owned by the Paris-based CPFK, including Video Futur and Video Pilote, developed a portable hard drive system called Moovyplay allowing customers to download video from in-store kiosks for play at home or on mobile devices.[xxxii] While Moovyplay seems to have been routed by on-demand distribution and widespread Internet piracy—many users employ this basic approach to download movies from the Internet onto personal hard drives and media players—such attempts demonstrate the current instability of video as a cultural form. This is signaled most clearly perhaps by the recent emphasis on processes like digital watermarking which attempt to control intellectual property by embedding “identifying data” into media content, “giving it a unique, digital identity.”[xxxiii] The Cinebank brand operates 34 video stores and automated machines in Paris, including the location we visited at 115, rue Oberkampf.[xxxiv] The site combines a 24-hour automated machine with a modest shop open three-to-four hours nightly, usually 5 pm to 9 pm, for in-store customers. At 1.5€ for a six-hour rental and 3€ for 24 hours, Cinebank outlets boast flexible rental periods and low prices. Unlike the gloss of Video Futur’s new storefronts, Cinebank is clearly targeted at lower income renters and so-called late adopters, who likely rely on VHS and DVDs. This fact is captured by the 1980s futurism of the shop’s marquee, complete with VHS tape, as well as the well-worn kiosk that now passes DVDs through slots originally intended for rectangular VHS tapes. Specialization In contrast to the modularity and convenience of automated systems and the Video Futur model, independent video stores employ alternative modes of survival. These one-offs rely on central neighborhood locations for regular traffic, and focus on inventory depth, distinctive layouts, and knowledgeable staff. Vidéosphère, a mammoth store at 105, boulevard St. Michel, boasts 34,519 films available for rent in store, not including nearly 3,500 VHS and DVDs for sale, as well as postcards, posters, film magazines and books, toys, and other memorabilia. Sorted by national and regional cinemas, award winners, new releases, film movements, directors and genre, Vidéosphère’s layout curates a particular experience of film history and its materiality. The thousands of VHS and DVD boxes on the store’s shelves, for instance, are only for show, as renters use reference numbers to rent titles at the counter, and leave the store with slender sleeves. The store’s numerous membership options also attest to the diversity of renters and habits. Starting at 4.5€ per film with yearly subscription (60€), and 6€ without, plans range from individual to cinephile and professional, including deals for weekends and, for the cinephile, five movies for five days for 22€, with subscription. Smaller stores, such as Clerks in the fifth arrondissement and JM Vidéo and Vidéo Club, both in the eleventh, also continue to eke out a living by combining new releases with large collections of French cinema, international art films, classical Hollywood, and other cinephillic fare. In each of these stores, owners explained that a large selection of classics, cult films, and documentaries, combined with popular new releases, remains one of their few remaining tools for competing with VOD and digital downloading. Several also referenced the continued importance of the store as a social space, where relationships and tastes co-evolve. In-store displays attempt to capitalize on the stores’ large and diverse stocks by recommending classics and art films rather than relying on new releases that are more easily accessible through other distribution sites. Stores such as JM Vidéo also attempt to bolster profits through additional services including DVD repair, as well as used discs for sale and a small back room with adult films. Most independent owners we interviewed allowed that the prospects for survival in the current market remain bleak at best (several admitted that they only hope to stay open for as long as possible). At the same time, the success of stores such as JM Vidéo (open since 1982) and more recently opened shops such as hors-circuits vidéoclub (opened in 2003), suggest that the independent model remains viable, at least in the short term. Clerks, for instance, benefits from its proximity to a large university population, including many foreign students. The shop even offers an English language website.[xxxv] Marginal and Interstitial Distribution Practices The dichotomy between sleek chains such as Video Futur and eccentric specialty outlets seems to define the current video store landscape in Paris. Most of the video stores in between have failed. However, glaringly absent from the above discussions are modes of formal and informal video distribution that exist outside the cultural center. From impromptu blanket-stalls in the metro tunnels, Indian CD and DVD shops in the neighborhoods around the Gare du Nord, and Chinese video stalls in the thirteenth arrondissement and the northern neighborhood of Belleville, to West African pornography at the Porte de Clignancourt flea market and Southeast Asian karaoke disc vendors, these sites represent critical and under-explored textures in the history of video stores and in film studies. Often relying on the sales of pirated material, and older formats like VHS and VCDs, fringe video shops and impromptu stalls cater to large populations in Paris whose needs are neglected by even Vidéosphère’s 35,000 titles or rent-by-mail and VOD services. If anything, the world cinema selections in stores such as Vidéosphère and JM Vidéo attest to the politics and impossibility of catering to this diverse market, while also suggesting the centrality of video stores as archives enunciating disparate forms of community within France. Conclusion One compelling aspect of our on-site research has been acknowledging our tastes and habits vis-à-vis video circulation. Not surprisingly, shops such as Vidéosphère and JM Vidéo appealed to our own cinephilia and familiarity with the independent video store model. These are, no doubt, the types of places mythologized in movies and by the recent outpouring of nostalgia for the social space of rental in the press and in passing conversations. Of course, a few such stores continue to exist, and more work can be done that explores their alternative potentials. They remain, however, relatively small ripples in the political economy of video. As Frederick Wasser describes in his essay in this issue, sites such as Kim’s Video in New York, Vidiots in Los Angeles, and, we would add, Vidéosphère in Paris are exceptions to the economic imperatives that underlie the bulk of video distribution: video stores did not create large markets for independent movies, fueled by “vidéomaniaques.” Instead, as even the independent store owners we interviewed remind us, they offer another profit channel for Hollywood blockbusters. Future research on video stores must continue to develop critical methodologies that move beyond the simple celebration of these sites. Alongside such extra-ordinary spaces, a different economy and culture of video persists in the form of popular chains like VideoFutur, automated Cinebank machines, online and rent-by-mail services, as well as largely unseen but increasingly important distribution channels that range from expensive satellite signals and fiber optic connections to the ephemeral, quasi-legal sites that serve minorities and marginalized communities in major Western cities. The trends suggested by contemporary Parisian video stores call for attention to these mainstream and alternative spaces, and for us, as fans, critics, and scholars, to revisit our assumptions about the place of the video store in film history and media industries. How, we must ask, can thoughtful historical, theoretical, and on-site engagements with the spaces of video circulation help us to understand and intervene in this changing, uneven landscape? Notes [i] We conducted interviews with video store owners at a selection of Parisian vidéo-clubs on April 6 and May 20, 2010. [ii] Chambre de Commerce et d’Industrie de Metz, Vidéo-Clubs (Paris: Centre d’étude du commerce et de la distribution, 1986), 8. See also Catherine Dupin, “The Video Market in France: Economics of a New Media,” Journal of Cultural Economics 12, no. 1 (June 1988): 87-96. During this period 766,000 VCRs were sold in France, raising the rate of French households with VCRs to approximately 4.6 percent. [iii] Christophe d’Yvoire, “Comment on devient vidéomaniaque?” Audio Vidéo Magazine 62 (October 1980); 45-46. Gérard-Jean Froment, “L’Explosion du marché de la vidéo,” Audio Vidéo Magazine 79 (March 1982); 78-92. [iv] Christophe d’Yvoire, “Cassettes vidéo : vive la location!” Audio Vidéo Magazine no. 74 (October 1981): 29-30. [v] Serge Le Péron, “Enquête. La vidéocassette est arrivé,” Cahiers du Cinéma: Le Journal des Cahiers no. 339 (September 1982): 1-11, 2. [vi] One high-profile case of piracy involved the Vidéo Club des Champs Elysées, a franchise with reportedly 160 stores in 1980, that was charged with renting illegally copied cassettes to customers paying 1000 Franc-per-year membership fees. The club faced an initial penalty of six months closure and a fine, followed by a second penalty of thirteen months probation and punitive damages. See “Les Pirates, L’ordre et la loi,” Cinéma de France : le mensuel de la profession no. 64 (April 1982): 43-44. [vii] The video release delay was later reduced to one year. The licensing fee was introduced as decree #82-971 of November 17, 1982 and went into effect in January 1983. [viii] “Poitiers : une autre sort de blocage,” Audio Vidéo Magazine no. 87 (November 1982): 1. [ix] Dupin, “The Video Market in France,” 89. See also Jacques Mousseau, “Le marché de la vidéo : naissance et croissance d'un « big business »,” Communication et Langages no. 90 (1991): 6-18, 7. [x] According to surveys and reports on Parisian video stores conducted in this period, even after six years business practices remained varied and in flux. Rental prices among stores covered in two separate surveys ranged from five to twenty-five Francs per cassette, and membership fees and terms ranged from 200 to 600 Francs per year for periods from three months to life. Stores tended to stock 250 to 500 cassettes (95 percent VHS), 70 percent of which, on average, were dubbed foreign films (mostly American). See Dupin, “The Video Market in France”; and Chambre de Commerce et d’Industrie, Vidéo-Clubs. [xi] French president François Mitterand announced the proposal for Canal+ in June 1982. Two more new channels—La Cina and TV6—appeared in 1986. [xii] Chambre de Commerce et d’Industrie de Metz, Vidéo-Clubs, 8. The report notes “amateurism no longer finds its place in this niche” (5). [xiii] Dupin, “The Video Market in France,” 93. [xiv] Mousseau, “Le marché de la video,” 15. [xv] The VCR license fee was repealed in Law #86-1067 of September 30, 1986 and decree #86-1365 of December 31, 1986. On falling cassette prices and Hollywood’s influence on the video sales market see Mousseau, “Le marché de la video,” 11. According to Mousseau, the French video market accounted for 1.7 million Francs compared to 1.5 million for cinema ticket sales (12). [xvi] In 1991 TF1-Vidéo, the largest French videotape distributor (albeit with only a 10 percent market share), reported that 75 percent of its business came from video sellers, compared with only 25 percent in 1987. Of that percentage, only 7 percent (or 77,000 cassettes) went to video stores, with 50 percent to large retailers and another 25 percent to wholesalers. See Mousseau, “Le marché de la video,” 13. [xvii] See Décision #05-D-18 relative à des pratiques mises en œuvre par la société Cinemat, Conseil de la concurrence, April 29, 2005. [xviii] See the figures published regularly by the Syndicat de l'Edition Vidéo Numérique, France’s video publishing and distribution trade union, available at http://www.sevn.fr. [xix] In stark contrast to its slow adoption of the VCR, by 1999 France was Europe’s largest DVD market. “VHS steady as French DVD sales surge,” Screen Digest no. 340 (February 2000). [xx] See Décision #05-D-18. [xxi] Molina Foix Vicente, “Un pays de pirates,” Libération, May 10, 2008, Week End section. [xxii] See “European Video: the industry overview,” International Video Federation 2006, available at http://www.ivf-video.org. [xxiii] See Sylvie Perras, “Les enjeux de la vidéo à la demande,” Cahiers du Cinéma no. 590 (May 2004): 75-78. [xxiv] See Samuel Douhaire, “Les vidéoclubs condamnés à évoluer,” Libération, May 20, 2006, Écrans section. See also Bouzet Ange-Dominique, “Le vidéo-club, un lieu de plus en plus virtuel,” Libération, April 6, 2006, Économie section. [xxv] Most recently, France has adopted a series of laws aimed at preventing service providers from allowing distribution of illegal content across their servers. These laws are typically refered to as HADOPI laws for the council charged with enforcing them, la Haute Autorité pour la diffusion des oeuvres et la protection des droits sur Internet. See Décret #2010-695 instituant une contravention de négligence caractérisée protégeant la propriété littéraire et artistique sur internet, June 25, 2010. [xxvi] Compare the Screen Digest figures cited in the 2006 and 2008 reports of the International Video Federation. “European Video: the industry overview,” International Video Federation, available at http://www.ivf-video.org. [xxvii] According to the 2008 International Video Federation report, although overall DVD rental in Western Europe fell by 12 percent in 2007, online rental rose by almost one third. See “European Video: the industry overview,” 2008, 12. [xxviii] See Vicente, “Un pays de pirates” and Catherine Balle, “Les vidéoclubs se spécialisent,” Le Parisien, January 30, 2010. [xxix] Now operating under the Video Futur brand, Glowria/Video Futur offer flat-rate rental-by-mail, video on demand (VOD) and IPTV distribution, access to videobanks as well as franchise store locations. At present, though, these disparate avenues are unevenly integrated and are hampered by separate operators for stores, banks, VOD, and the like. [xxx] “Où trouver nos Magasins,” Video Futur, http://www.glowria.fr/viewEditoFull.do?editoid=1325 (accessed August 10, 2010). [xxxi] The business model is similar to Blockbuster Video’s current strategy in the US. See, for instance, Blockbuster’s current homepage, http://www.blockbuster.com (accessed November 10, 2010). [xxxii] “New Service to test Kiosk-to-hard-drive Movie Rentals this Fall.” Originally reported in Video Business, and circulated online at http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/news/2007/08/new-service-to-test-kiosk-to-hard-drive-movie-rentals-in-the-fall.ars (accessed August 8, 2010). [xxxiii] “Media Advisory: Digital Watermarking Alliance Reports New Options for Deploying Digital Watermarking, and Increased Adoption Across Media Landscape,” The Digital Watermarking Alliance, http://www.digitalwatermarkingalliance.org/pr_041008.asp (accessed August 1, 2010). [xxxiv] A list of store locations in France can be found on Cinebank’s website, “Mon Cinebank,” http://www.cinebank.fr/site/pages/2/13/_7_13_01.ph (accessed August 15, 2010). [xxxv] “Clerks Vidéo Club,” http://www.clerksvideo.com/site/index.php?lang=en (accessed November 10, 2010). Brian R. Jacobson is a Ph.D. candidate in Critical Studies at the University of Southern California. He has been a Fulbright Advanced Student Fellow to France and a fellow of the Social Science Research Council’s International Dissertation Research Fellowship. His dissertation, Studios Before the System: Architecture, Technology, and Early Cinema, traces the history of film studios and studio architecture in the United States and France before 1915. Joshua Neves is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Film and Media Studies at UC Santa Barbara. He is currently completing a dissertation entitled “Projecting Beijing: Screen Cultures in the Olympic Era.”

Post a Comment

Post a Comment