Four Theses on Formal Chronocentrism: Forgetful Reception of Recent Film and TV Cycles

Wednesday, May 19, 2021 at 3:09PM

Wednesday, May 19, 2021 at 3:09PM Marc Francis

[ PDF Version ]

Most scholars of remakes, reboots, and updates agree that it doesn’t seem to hurt a film or TV series to identify itself as a remake or update. On the contrary, producers, filmmakers, advertisers, studios, networks, and streaming providers are quick to, as Rudiger Heinze and Lucia Kramer put it, “flaunt the fact to capitalize on the audience’s familiarity with the original.”[1] But while clear remakes such as A Star is Born (dir. Bradley Cooper, US, 2018) and Stephen King’s It (dir. Andy Muschietti, Canada/US, 2017) draw mass audiences, there exists an adjacent contemporary trend of films and television series, one arguably more perplexing yet telling of our current moment and its relationship to history. This trend concerns updates that camouflage their source material, revising the stylistic features of their precursors for forgetful audiences.

Let me couch this point in the form of a pitch. Let’s say you are a television executive, and I am a writer or agent selling you on a series. The pilot opens with a violent death. Who has been killed? By whom? For what reason? A close-knit affluent community is shaken by the mystery. We zero in on a group of women, mostly middle-aged, linked somehow to the tragedy. As the season unfolds, we become more and more privy to the lies these women tell others and themselves, which in turn bring them closer together and closer to the truth.

Name that show. If you said Big Little Lies (HBO, 2017–2019), you are right! And if you said Desperate Housewives (ABC, 2004–2012), you are also right, but likely in the minority.

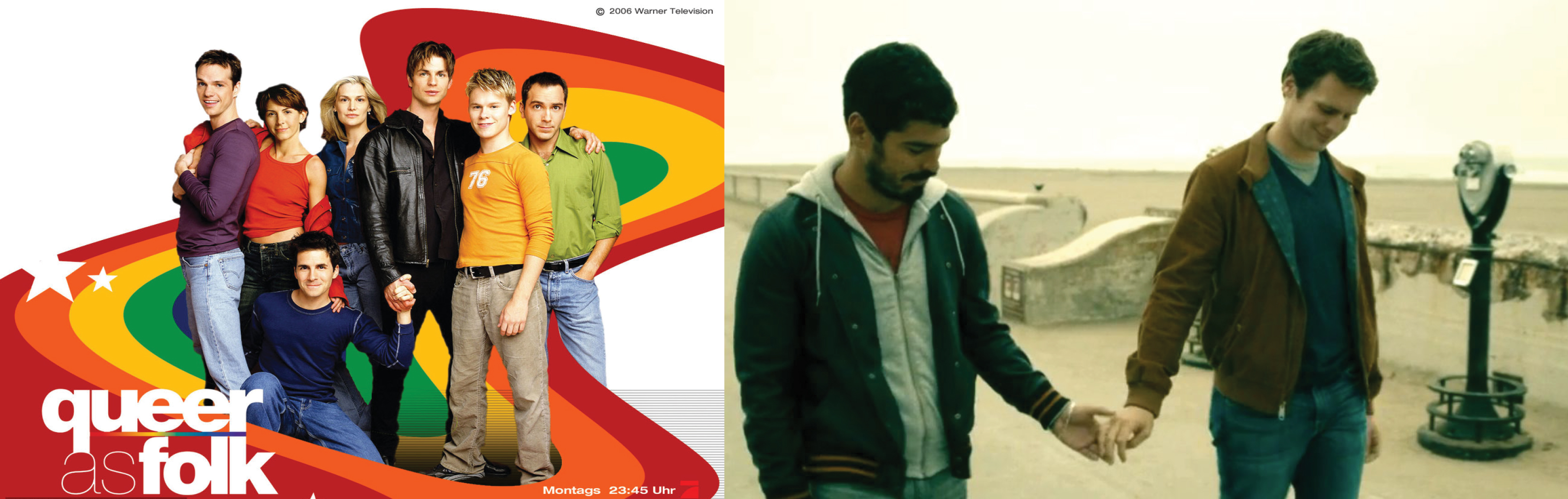

Let’s do another one. Family is family, even when it’s chosen. This drama follows the vicissitudes of five(ish) gay men as they try to find love, work, and meaning in the big city. Our central anchor for the story is a nerdy hopeless romantic who, unlike his friends, is looking for the real thing. While their philosophies, personalities, and backgrounds continually clash, they remain a family through and through. They support one another and discover new sides of themselves as they navigate the confusing codes of sex and romance set against a contemporary “liberated” urban backdrop.

What is the show? Most readers—especially those younger and queer—will likely say Looking (HBO, 2014–2015). Some might say Queer as Folk [US] (Showtime, 2000–2005), its predecessor.

The point of this exercise is to show that critical and fan circles rarely discuss the resemblances between Looking or Big Little Lies and the earlier texts Desperate Housewives and Queer as Folk, both of which came (not so incidentally) between fifteen to twenty years before. Whether by accidental omission or deliberate dismissal, such an oversight implies that the hypotext—the text that the update seeks to revise—is a historical relic devalued for its lack of tonal, aesthetic, and ideological relevance to the current moment and mood. Sociologist Jib Fowles calls this kind of temporal eclipse “chronocentrism,” which he defines as “the belief that one’s times are paramount, that other periods pale in comparison.”[2] The turn to “quality” in television, alongside advances in digital television and film production, I argue, have yielded a cycle of updates that attempt to quietly take narrative premises with nearly identical story structures and casts of characters and recast their use value within the lauded pseudorealist stylistic trends of the current moment. I call this paradigm formal chronocentrism.

To be clear, I am not lamenting the loss of originality or proper intertextual citational practices; all creative work, one can easily argue, is derivative in some form or another—that is not a bad thing![3] Instead, my concern is that public media reception has turned away from discourse on intertextual media genealogies, unless the text is a clear remake in name (such as with Ryan Murphy’s Boys in the Band (US, 2020) or The Craft: Legacy (dir. Zoe Lister-Jones, US, 2020)). By too often ignoring the hypotext, critical discourses implicitly deem the updated iteration more sophisticated than its source material, a stylistically mature version of an inferior object that doesn’t require reference. This sly omission in critical and fan reception encourages viewers to forget the complex and insightful cultural and political work these past texts have done and even still might do.

This is why I am opting to use the term update rather than remake here, to highlight that time’s passing is these texts’ raison d’être, and that their success depends to an extent on a forgetful or amnesic viewership. Mary Ann Doane’s insight that “television thrives on its own forgetability” is still germane in this sense, even though her observation long predates television as we know it today.[4] As streaming overtakes linear programming, and the content industry supplants the TV and film industries, TV’s own disposability still marks the medium’s ontology. New releases pour into streaming apps each week, engulfing consumer attention to produce a myopic state both present and future-bound. When media memory becomes a financial liability—an obstacle in selling the newness of content—the business model requires viewer amnesia.

As Thomas Leitch points out, most remakes exist to adapt the original to the thematic, social, technological, and stylistic resonances of contemporary life.[5] Past forms can fail modern audiences, whom, Leitch suggests, are prone to be presentist or chronocentrist in their predilections. This is not necessarily a new phenomenon. However, unlike the B-movie remakes of the 1940s and 1950s or other predigital examples, this current variant of formal chronocentrism wields technological advances in digital aesthetics, producing what many call a “cinematic look” that is often realist in tone and texture. By realist, I mean an aesthetic and performative mode that, in contrast to classicism, privileges an unpolished and “gritty” depiction of life that is purportedly free of perceived overstylization and mannerism.[6] These updates’ realist tonal and aesthetic refashioning befits a culture presently obsessed with self-truth and authenticity, and a culture in which attention to derivation and recurring media life cycles undercuts a work’s ability to truly live in and speak to the present that we all supposedly share.

Looking, Big Little Lies, and the film The Miseducation of Cameron Post (dir. Desiree Akhavan, US/UK, 2018)—the titles I will focus on here—share a kind of formal conceit, in multiple senses of the term. In one sense, these examples share creative devices or properties; in another, they exhibit a kind of conceit, priding themselves on their formal accomplishments. Audiences and critics inflate their novelty, thus giving these works a sense of cosmetic conceit in relation to their earlier analogues. In contrast to Queer as Folk and Desperate Housewives, which lean into pulp and camp, Looking and Big Little Lies strive for what Vulture critic Matt Zoller Seitz calls—in his review of the Looking pilot—an “intimate shooting style,” along with editing and acting techniques that are meant to give the viewer a feeling and perception of verisimilar immediacy.[7]

In what follows, I expand upon these attributes by proposing four theses on the notion of formal chronocentrism as it persists today. These four theses by no means aim to comment on all contemporary remakes or updates, though one could find critical parallels to even those recent remakes that announce themselves as such.[8] I conclude by suggesting that these examples reveal a problem in our current relationship to style and history, which obscures the reproduction of the past in our present.[9]

Thesis one: formal chronocentrism is remedial. As I have already indicated, these new iterations of older media imply that there is something passé in the hypotext’s style yet still relevant in their narratives’ structuration. Big Little Lies, though adapted from a novel, seems to base its serial premise and structure more on Desperate Housewives. The two series share many of the same tropes but, unlike Desperate Housewives, Big Little Lies promises an inner depth for its cast of female characters. The series transforms the melodrama-bordering-on-farce of Desperate Housewives into a quiet, stripped-down, and precious melodrama.[10]

Take Emily Nussbaum’s review of Big Little Lies’ first season as representative. Nussbaum writes that, “while the show begins with a Schadenfreudian air—like a prestige-TV twist on the Real Housewives franchises—it deepens. Generous to its characters, even those who begin as clichés, the series becomes a reflection on trauma; at its best moments, it makes risky observations, especially about the dynamics of domestic abuse.”[11] Nussbaum sees Big Little Lies as commendable for its earnestness—a proper antidote to crude content that only makes a spectacle or mockery of rich (mostly white) lady issues. She suggests the series has taken themes such as domestic violence and trauma seriously in a way that neither soap operas (daytime or evening) nor unscripted TV has been able to, and for that decision, it is almost feminist in its depiction. Peculiarly, Nussbaum does not mention Desperate Housewives in her review, opting instead for The Real Housewives (Bravo, 2006–) as the more current counterpoint.

A still from Desperate Housewives (left) and promotional ad from Big Little Lies (right). Many of the character archetypes cut across the two texts, but their styling and coloring are worlds apart.

But isn’t it odd, given the similitude? Nussbaum admits that Big Little Lies is remedial—a “prestige-TV twist”—and yet she bypasses the more conspicuous analog, perhaps to stay current, or perchance to avoid risking comparison with Desperate Housewives altogether. Such a comparison might prompt her to ask: did Desperate Housewives not also comment on gender, on wealth, on the concessions women make for their husbands, the ways that normativity makes crazies of us all—laughter turning into tears and back into laughter, the hysteria that haunts Wisteria Lanes all over the country? I ask: what do we lose, then, in forgetting Wisteria Lane?

This unironic, un-self-conscious, some might say “raw,” rendering of trauma that Nussbaum and other contemporary critics celebrate can also be found in The Miseducation of Cameron Post, which won the 2018 Grand Jury Prize for US Drama Feature Film at Sundance. Another intellectual property that is based on a novel, the film chronicles a teenage lesbian’s experience at a gay conversion therapy camp. Though rarely discussed, it is a quiet remake of the 1999 queer cult film But I’m a Cheerleader (dir. Jamie Babbit, US) starring Natasha Lyonne. In one interview with Miseducation’s director Desiree Akhavan, the interviewer even draws a comparison between the two works. Akhavan, in response, stumbles and provides a contradictory explanation. “I love [But I’m a Cheerleader],” she says, “. . . My cowriter and I talked about it . . . [but] we didn’t even watch it again. We didn’t want to have it in our heads and feel influenced without realizing it . . . But they’re just completely different films that happen to be about the same subject.”[12] Such a disingenuous response papers over one of the primary reasons the update exists. Miseducation, I argue, tries to revise the camp sensibility that saturates the pink-and-blue mise-en-scène and intentionally overstated acting style of But I’m a Cheerleader. Such circumstances, Akhavan’s film suggests, needs a muted (if not drab) style to fit Trauma with a capital T, the buzzword of the day. Trauma is not arbitrary here; it is a metonym for realism, a goal of formal chronocentrist remediation.

The monochromatic pink design of the campy But I'm a Cheerleader (left) juxtaposed with the muted color palette of The Miseducation of Cameron Post (right), the latter of which aesthetically unites gen-X grungy angst with millennial obsession with trauma.

Thesis two: Formal chronocentrism strives for realism. The mise-en-scène and editing of Big Little Lies, Looking, and Miseducation aim to resemble the “grit” of the world their creators and critics assume that the viewer occupies.[13] Directors Jean-Marc Vallée (Big Little Lies) and Andrew Haigh (Looking) have taken cues from the neorealists, “vérité” and direct cinema filmmakers that came before them, building careers on shaky, gritty handheld cinematography. Historically, various schools of realism tended to focus on working class and other social problems; in contradistinction to classicism, they usually harnessed realist aesthetics for leftist political projects. Shows like Big Little Lies and Looking have little to no investment in social justice causes. Realism for them is commercially viable because it is a shorthand for trauma, a current cultural obsession. Couched in realist techniques, the trauma here is all the more immediate, the dullness of real life painfully, beautifully inescapable. At least for a certain audience.

It is no coincidence that Looking, like Big Little Lies, chooses Northern California as its locale. Narratively, it drives the tensions around class and race set against the backdrop of unrelenting and traumatizing gentrification, but visually, it also allows the producers to recast San Francisco as the gray, foggy city you don’t see in Vertigo (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, US, 1958) or the original Tales of the City (Channel 4, 1993). If Vertigo is the crown jewel of Technicolor greatness, then Looking might be its opposite. The show reframes San Francisco as a close cousin to cloudy and chilly Nottingham, England, where the show’s executive producer Andrew Haigh set his career-launching film Weekend (UK, 2011).

HBO's Looking (right) recycles many of the same storylines and issues explored in its hypotext Queer as Folk (left), but trades the rainbow color palette and high-key lighting for color desaturation and a faded look reminicent of an Instagram filter.

Looking’s dull earth-tone color palette and handheld techniques combined are likely what lead New York Times television critic Mike Hale to cheer the show’s “authenticity.” “It feels real,” Hale claims, noting that the characters “talk and act like real people.”[14] (Note that similar to Nussbaum’s omission of Desperate Housewives, Hale doesn’t mention Queer as Folk.) But dialogue does not work in a vacuum; aided by tight medium shots and close two shots, Looking by implication strips its most convenient hypotext, Queer as Folk (UK and US versions), of its intentional camp and play with identity archetypes or constructions. Looking replaces the causticness of Queer as Folk, which followed The Boys in the Band (dir. William Friedkin, US, 1970) in a long tradition of mordant gay humor and self-deprecation, with dialogue and a mise-en-scène that is meant to be subtle, oblique, and pregnant with undertones. Just as Big Little Lies did with Desperate Housewives, Looking also sticks to the character archetypes of its hypotext, but they are now augmented by the illusion of nuanced form.[15] In this formula, nuance no doubt equals authenticity: the image is decamped in the name of trauma, verisimilitude, and complexity.[16]

Thesis three: Formal chronocentrism is about artfulness and thus aims for distinction and high(er) taste. By now it’s a cliché that television is looking more and more “cinematic.” Indeed, this may be true, as more and more shows and movies adopt the pseudorealist formal conceit that I have outlined here. Much television seems to offer the kind of realist understatement that had previously been reserved for art cinema. In this sense, understatement is an indicator of taste, which, Pierre Bourdieu has demonstrated, is historically and culturally contingent.[17] Television scholars Robert J. Thompson, Janet McCabe, Kim Akass, and Jane Feuer, among many others, have observed that HBO—the ultimate case study in understated TV—was on the forefront of this shift by the late 1990s, its product predicated on distinction.[18] In the age of streaming and “content creation,” other networks and content providers have followed suit, exploiting understatement as a lucrative asset. Ironically, for the average viewer, it can now be accessed relatively cheaply.

The use of color is an excellent barometer of marketable distinction. To again employ the Northern California examples, the goal now seems to be to limit the color palette of a show’s overall design. The colors in Queer as Folk had a vibrant range, reminiscent of the queer community’s rainbow flag, whereas the colors in Looking are stultified, as if the costumes and furniture have gone through too many thrift stores and Instagram filters to count. Limiting a show’s color palette (to the same set of earth tones again and again) gives a sense that Big Little Lies, for instance, has the touch of an artist or designer who carefully curates a show’s mood. The chilly dark blue of the ocean is mirrored in the influencer-style homes the characters inhabit, stirring audiences to fetishize the pictured homes while they take pleasure in their own sophisticated tastes.

Contemporary lighting technique is another perfect indicator of the distinction paradigm nestled in form. Shows from The Handmaid’s Tale (Hulu, 2017–) to Jessica Jones (Netflix, 2015–2019) to Game of Thrones (HBO, 2011–2019) seem to get dimmer and dimmer to the point where the image wanes from visibility. This descent into darkness tracks apace with formal chronocentrism, marking a new chapter of what has been deemed “quality TV” or what Jason Mittell calls “complex TV.”[19] Compare the uniform, often high-key lighting of series that aired around 2000 with television shows today; for this reason, Mittell’s examples of televisual complexity seem already out of date. As an example: each semester I teach Veronica Mars (UPN, 2005–2006), a show that many scholars regard as “complex,” coupled with Jessica Jones, to show students feminist televisual revisions of the noir genre. Without fail, most students describe the pilot of Veronica Mars as hokey or campy compared to the sleek Jessica Jones. They can’t even take seriously Veronica Mars’s themes of sexual violence, depression, racial and class difference, and bullying because it lacks the prestige look of a show like Jessica Jones. In her “Notes on Camp,” Susan Sontag suggests things are campy when we become “less involved in them,” and my students’ reactions not only prove this, but perhaps push it to its ethical limits.[20] This is not my students’ fault; they live in a culture duped into valuing content that looks highbrow and sophisticated—regardless of its deeper implications—and devaluing its inverse.[21]

Thesis four: Formal chronocentrism showcases advancements in digitized aesthetics. Television’s dark turn, its love affair with color desaturation, and its penchant for the shaky frame are all the more possible thanks to progress made in the areas of digital cinematography and postproduction software (e.g., CGI and color grading). The coveted twenty-four frames-per-second look is now more easily obtained. With footage from high-definition cameras, watched on high-definition televisions or devices, recycled intellectual property looks and feels different, which translates to the perception that the texts that correspond to these technological and formal modes are completely different.

Technological progress often motivates remakes and updates, as Constanine Verevis points out about Peter Jackson’s 2005 remake of King Kong (New Zealand/US/Germany).[22] The special effects that were awe-inspiring in 2005 are now essential components to postproduction, even for dramas such as Big Little Lies that don’t appear to need it. Formal chronocentrist media prides itself on its casual use of special effects and other digital tools that are at its disposal. Unbeknownst to the average viewer, it flaunts that which its analog couldn’t do aesthetically. It’s a 4K facelift without any blemishes, erasing any sign of the textual palimpsest.

The cafe in Big Little Lies was actually shot on a soundstage using green screen technology. There are countless other instances of shows that do not appear to need special FX, yet use postproduction equipment and software to achieve a polished look.

Why does formal chronocentrism matter? First, from an industrial standpoint, identifying formal chronocentrism might help dispel the common myth that television as of late is willing to take more risks than film. Recycled narratives, even when people fail to see them as such, indicate that television is also highly risk averse. Both industries rely heavily on genre to help orient investment. Formal chronocentrism, however, pulls even the most informed viewers back from acknowledging generic conventions, occluding what they might otherwise detect as familiar. Call it an affective fallacy, formal chronocentrism convinces audiences that they have unmediated access to a more genuinely told story with characters that are textured and real enough to touch, and a place and time that resembles our own. The technological advancement of digital aesthetics thereby becomes grafted onto realist formal devices, naturalizing them both.

In its most deceptive moments, formal chronocentrism gives the impression of progress. To again use the example of Big Little Lies, failing to admit that this series is, under its veneer of artfulness, tawdry soapy melodrama is the logical inverse of saying that a show such as Desperate Housewives lacks thoughtful insights into gender, class, race, trauma, and sexuality because of its campy form. These cases demonstrate that relevance too often maps onto style, an issue that is at times taken for granted in film and media studies.

Above all, today’s manifestation of formal chronocentrism certifies that we live in amnesiac times. At our typing fingertips are reminders of past and reproduced sins. Yet, paradoxically, one scandal rolls into the next, corruption leads to more corruption, one violent act to another; the rolling feeds of social and news media means we are quick to forget and loathe to remember. Formal chronocentrism adheres to the same logic: it delivers immediate gratification without the need for historical reflection. When critics and audiences alike ignore the previous incarnation of a work, especially when that work was groundbreaking for its own reasons, they are forgetting history, the important critiques, commentaries, or queries that media has made and can continue to make, all because the style may feel outmoded or distant. Such duped viewers are playing a game of the emperor’s new clothes. But as the tale goes, it only takes one person to expose the lie, to begin to unspool the cloak that was never really there to begin with.

Acknowledgement: A version of this essay was delivered at the 2019 Literature/Film Association’s conference, “Reboot, Repurpose, Recycle.” I was generously awarded a travel grant by a selection committee who made my attendance possible. I want to thank LFA board members Pete Kunze, Marton Marko, Walter C. Metz, Amanda Konkle, and the other members for their support, as well as the conference attendees who provided feedback on my paper.

Notes

[1] Rüdiger Heinze and Lucia Krämer, eds., Remakes and Remaking: Concepts, Media, Practices, (Bielefeld, DEU: Transcript, 2015), 8.

[2] Jib Fowles, “On Chronocentrism,” Futures 6, no. 1 (1974): 65.

[3] To speak specifically to commercial arenas of the moving image, film studios and television networks have a long history of self-plagiarizing. Miranda Banks attests to this in her book The Writers: “The studios did come up with ingenious, if devious methods for getting new material. Perhaps the most audacious was that of Warner Bros. Producers. Nonwriters—perhaps secretaries or associate producers—took scripts from one series and switched around characters and locales, thereby turning what might have been a detective series into a Western, and then the companies filmed an episode.” I thank Annie Berke for bringing this source to my attention.

[4] Mary Ann Doane, “Information, Crisis, Catastrophe” in Logics of Television: Essays in Cultural Criticism, ed. Patricia Mellencamp (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 226.

[5] Thomas M. Leitch, “Twice-Told Tales: The Rhetoric of the Remake,” Literature/Film Quarterly 18, no. 3 (July 1990): 138–149.

[6] TV producers Ryan Murphy, Marc Cherry, and Eliot Laurence are some successful exceptions to the turn towards earnestness in dramatic television. The queer appeal of their soapy serials is a warranted subject for a longer article.

[7] Matt Zoller Seitz, “The No-Fuss Radicalism of HBO’s Looking,” Vulture, 16 January 2014, www.vulture.com/2014/01/tv-review-hbos-looking.html.

[8] The Batman franchise’s evolution over the years—up to the recent Joker (dir. Todd Phillips, 2019)—perfectly illustrates this. Note how Tim Burton’s pulpy, cartoonish Gotham (Batman, US/UK, 1989) morphed into Christopher Nolan’s Chicago-like Gotham (Batman Begins, US/UK, 2005), which has more recently transformed into the gritty 1970s-New York-like setting for Joker, the antihero psychological character study of the classic villain. Director Todd Phillips conceives of an Arthur Fleck (here, the Joker’s real name) that seems like a neighbor who lives down the hall in a Gotham you could inhabit. Similarly, TV shows and films part of streaming providers’ (e.g., Netflix, Paramount Plus, and Peacock) “reboot fever” offers a strange twist on this idea. They revive intellectual property to monetize the contemporary version’s superiority to the “original.” With hit reboots and remakes such as Queer Eye (2018- ) and Chilling Adventures of Sabrina (2018-2020), it seems fair to suggest Netflix has become an assembly line for chronocentrist content.

[9] To take a highly successful counterexample, Ryan Murphy’s production vision generally works in dialogue with past media. Pose (FX, 2018–) and Feud (FX, 2017) are two stellar cases. Conversely, Hollywood (Netflix, 2020), though it engages overtly with old Hollywood, devolves into wish fulfillment fantasy and therefore loses any ties to history, lived or speculative.

[10] To be more specific, the first season is guiltier of this than the second. The first half of season two, amplifies the soapiness by bringing in the character Mary Louise (Meryl Streep). The second half takes itself more seriously. Anecdotally, I watched the second season with a group of mostly gay men and some straight women. We all agreed the first half of the second season was much more interesting than its conclusion.

[11] Emily Nussbaum, “Beaches,” The New Yorker, 6 March 2017, 82.

[12] Anna Swartz, “Desiree Akhavan Made The Miseducation of Cameron Post for ‘Everybody,’” Mic, 1 August 2018, www.mic.com/articles/190547/desiree-akhavan-the-miseducation-of-cameron-post-interview.

[13] It should be acknowledged that something strange happens to the formal chronocentrist seriousness I am addressing when films and TV shows such as Big Little Lies are turned into memes and other remixed online content. This paratextual extraction usually ends up inviting a degree of irony and humor that may be buried in the object. By isolating certain moments, performances, or bits of dialogue, social media content can produce a camp text out of an otherwise earnest one.

[14] Mike Hale, “Authentic Characters Seeking Sex and Romance, and a Future on HBO,” The New York Times, March 22, 2015, www.nytimes.com/2015/03/23/arts/review-hbos-looking-has-season-finale-but-no-word-on-its-future.html.

[15] Arguably Girls (HBO, 2012–2017) does the same with Sex and the City (HBO, 1998–2004), though with a bit more of a nod to it than the examples that I discuss in this essay.

[16] Bradley Cooper’s 2018 version of A Star is Born is a particularly bizarre example of this quest for authenticity. In a New York Times op-ed, Kyle Buchanan chides reviewers and fans of A Star is Born for their embarrassed and apologetic affection for the film. Citing memes and other circulating social media posts, Buchanan suggests that people are not allowed to have genuine relationships to sentimental media anymore. (It’s hard to agree when there are so many accounts of people crying and cheering the film’s dramatic and musical achievements.) The piece wonderfully illustrates a shift in celebrating authenticity and deriding irony. Kyle Buchanan, “Is A Star is Born Campy, or Have We Forgotten How to Feel?,” New York Times, 7 October 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/10/07/movies/a-star-is-born-camp.html.

[17] See Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984).

[18] Robert J. Thompson, preface to Quality TV: Contemporary American Television and Beyond, ed. Janet McCabe and Kim Akass (London: IB Tauris, 2007), xvii–xx; Janet McCabe and Kim Akass, “Sex, Swearing, and Respectability: Courting Controversy, HBO’s Original Programming, and Producing Quality Television,” in McCabe and Akass, Quality TV, 62–76; Jane Feuer, “HBO and the Concept of Quality TV” in McCabe and Akass, Quality TV, 145–57.

[19] Jason Mittell, Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling (New York: New York University Press, 2015)./p>

[20] Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation, and Other Essays (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1966), 285.

[21] To be clear, I do not think Jessica Jones is devoid of substance. I am referring to the overall problem in this specific sentence.

[22] Constantine Verevis, “Remakes, Sequels, Prequels” in The Oxford Handbook of Adaptation Studies, ed. Thomas Leitch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 269.

Marc Francis is a Lecturer at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, CA. He received his PhD in Film and Digital Media Studies from the University of California, Santa Cruz. His essays have appeared in Camera Obscura, Jump Cut, Film Quarterly, and [In]Transition.