Japan Sea(s)

Monday, March 9, 2020 at 5:09PM

Monday, March 9, 2020 at 5:09PM [ PDF Version ]

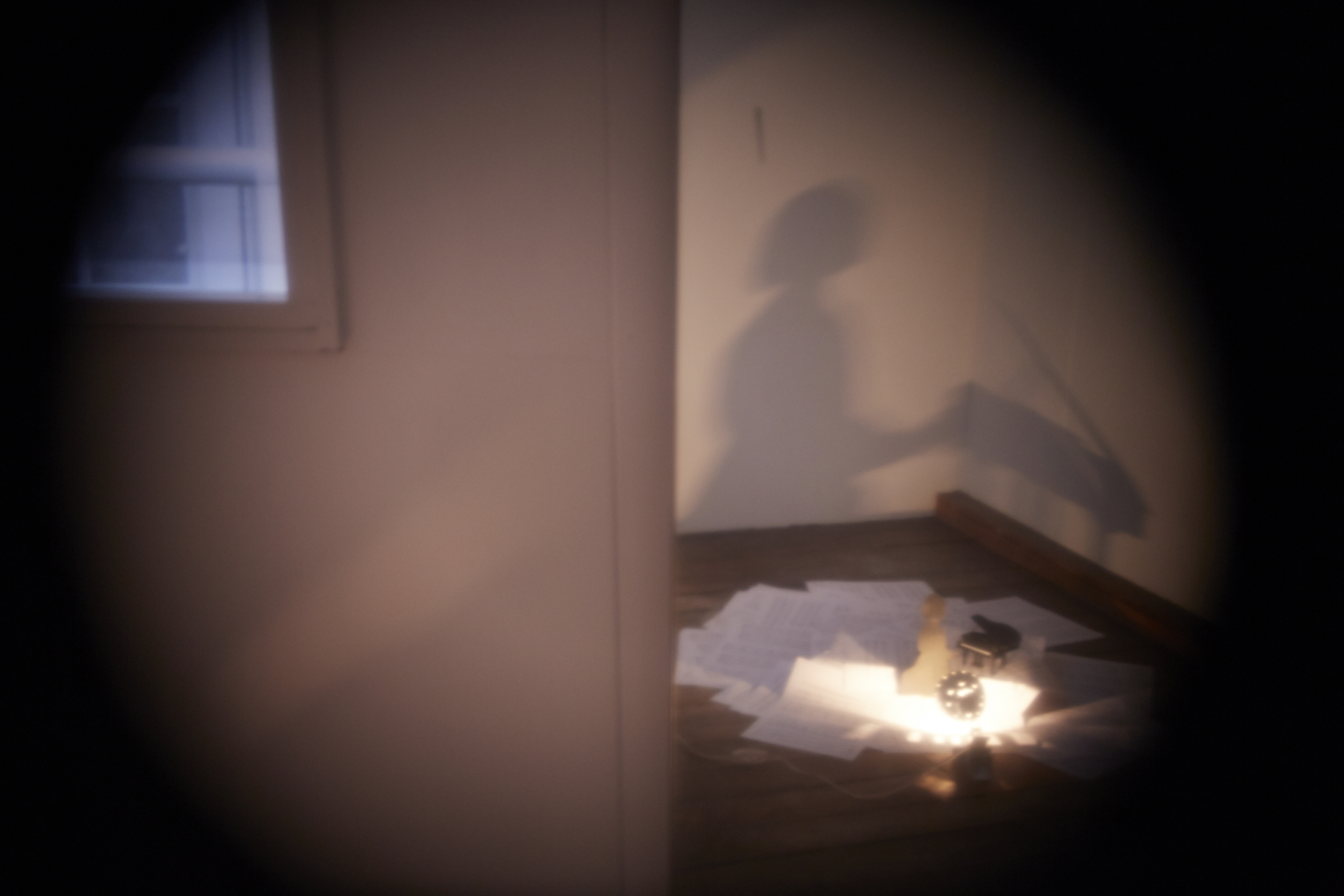

Figure 1. Port of Dream (2014), Cindy Mochizuki. Koganecho Art Bazaar, Fictive Communities Asia, 2014. Koganecho, Yokohama, Japan. Curated by Hakiko Hara. Photo courtesy of Koganecho Art Bazaar.

Editor’s Introduction: I first encountered Cindy Mochizuki’s work in the midst of completing research for my MA thesis, which considered how multidisciplinary and screen artists working in post-9/11 Canada engaged the entangled histories of settler colonization and migrant exclusion that found and sustain the Canadian national project.[1] My aim was to think about how such creative engagements might aid in critically reframing and contesting what was then a nascent regime of border governance, built around strategies of preemption, interdiction, surveillance, and incarceration that unfolded mostly away from the border itself. The task was to account for how the often unbearable pressures of bordering—pressures that descend all the more intensely on those whose bodies do not abide the normative Whiteness of the idealized and, in Sunera Thobani’s words, “exalted” national subject—had, in the years since 2001, been displaced and diffused through the social body, multiplied and redistributed such that post-9/11 demands for a radically expanded security apparatus could be reconciled to those discourses of tolerance and diversity that fill out the Canadian state’s promise of liberal multiculturalism.[2]

Such were the intellectual and political conditions of my earliest engagements with Cindy’s practice, which drifts delicately between installation, performance, sculpture, video, animation, embroidery, audio, drawing, and even food preparation. In her work, I could discern the inklings of a radically otherwise imaginary of both the transoceanic and the transnational, an alternative cosmology of movement, memory, and (dis)connection that squarely confronts painful histories of (state) violence even as it invites us to feel our way toward new, more just modes of encounter and assembly. In hushed tones, without bombast, it seemed to open an affective pathway out of the punishing intensities of what I had begun to call the Canadian state’s atmospheric bordering regime. Since this time, Cindy’s work has remained a vital point of reference in my thinking; a constant reminder of what, politically, becomes possible when our ways of seeing, knowing, and feeling history are differently arranged.

Out of difficult and deeply personal memories of transpacific immigration, Mochizuki assembles oneiric sensory environments where restless ghosts—eager to speak but just as ready to listen—mingle with the living. Together, they weave intricate and unexpected stories about displacement, global conflict, and remembrance; about home, being far from it, and sometimes going back to it; about family, and about monsters. I have always thought of Cindy’s works as gathering spaces; sites where the dead and the living, the past and the present, what’s remembered and what’s yet to come, enter in and are welcomed. In these haunting and haunted places, new ways of thinking about history and our different ways of being in its thrall bubble to the surface. These other histories involve, and are involved in, the history of Pacific empire. For example, the forcible internment of some 22,000 Japanese men, women, and children by the Canadian government during the Second World War, and the subsequent repatriation of thousands of former internees to Japan, hang heavy over much of her oeuvre. But the ghost stories told in Mochizuki’s work are also not exhaustively of this history. They cut alternative pathways in time and space by introducing into the structured narratives of history and archive the contingencies of magic and conjuring, the clairvoyance of fortune reading, the hazy spectrality of apparition, and the intense intimacy of the home video, the souvenir, and the trinket.

As we were preparing this special issue, considering what analytic frames might best sharpen our sense of the Pacific as a complexly imperialized terrain where decolonizing and unsettling ways of knowing-being-feeling nonetheless remain in circulation, I could not help but think of Cindy’s work. Thrumming with energies occult and metaphysical even as it remains, in its subject matter, gravely attuned to the traumatic histories of displacement and transit that churn in the waters of the imperial Pacific, Cindy’s work does not aggressively shatter inherited ways of seeing and knowing, but rather delicately rearranges the weave of things; loosening certain knots and prizing loose certain joints, making room for others. In what follows, Cindy generously responds to an invitation to reflect on the transpacific as an intellectual and cultural formation, and to explore how that formation has shaped her practice. The story she tells, in a certain sense, is about the disorienting conditions under which she created her 2014 work, Port of Dream, documentation of which is included below. But in another, it is about the insistent demands of memory, how they chafe against what we call history, and how the task of making images and telling stories about the imperial Pacific finds itself mired in the brackish currents that pass between the two.

-Tyler Morgenstern

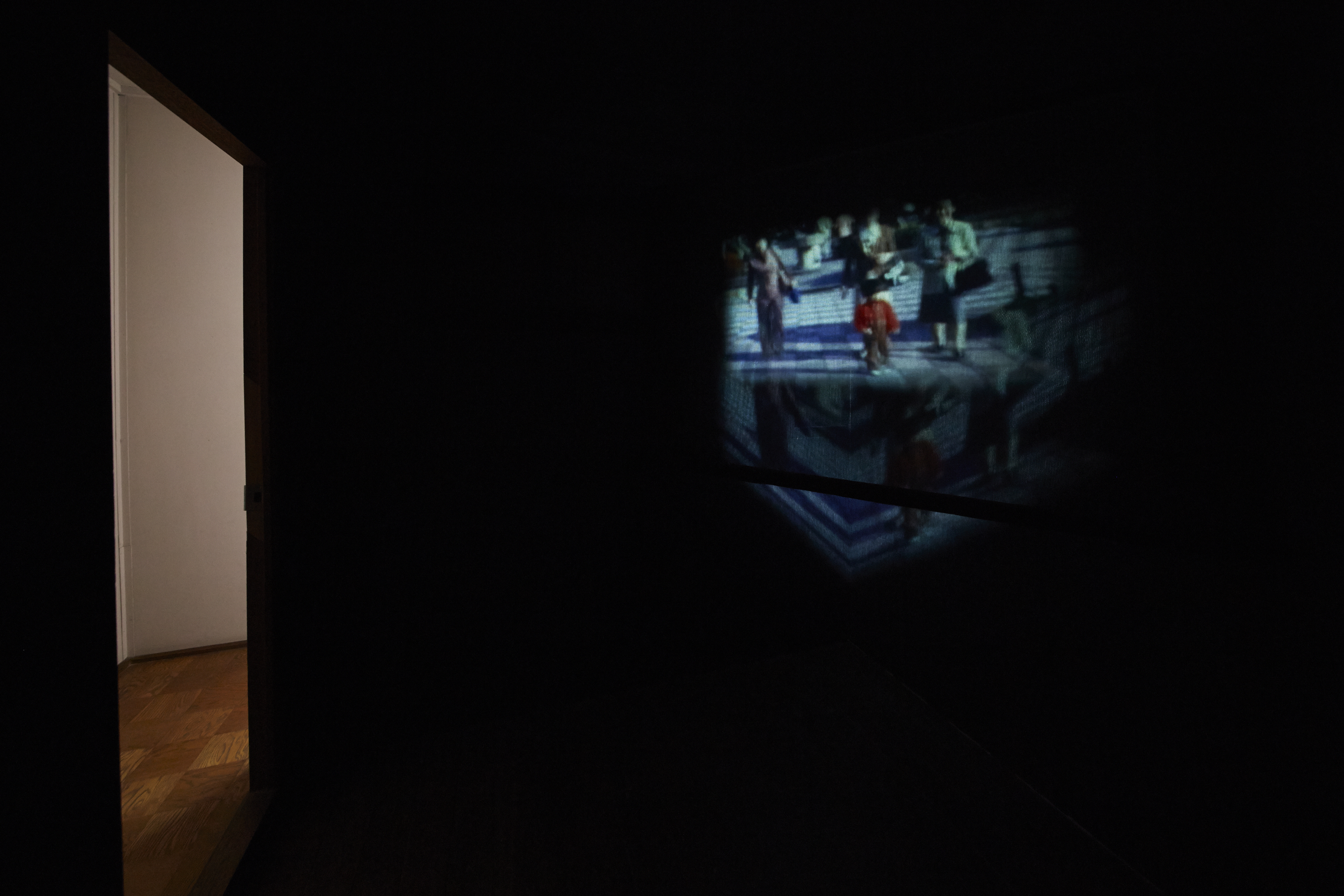

Figure 2. Port of Dream (2014), Cindy Mochizuki. Koganecho Art Bazaar, Fictive Communities Asia, 2014. Koganecho, Yokohama, Japan. Curated by Hakiko Hara. Photo courtesy of Koganecho Art Bazaar.

1. I am frozen in the state of kanashibari, and beset with jetlag;[3] a time difference of seventeen hours, the night I arrive to be part of the 2014 residency of the Koganecho Bazaar in Koganecho, Japan.[4] As I clutch my cell phone and attempt to fall asleep, I begin to hear sounds in the paper-thin walls that begin to creak and scuttle like the feet of tiny summer cockroaches. A shadow flits by and I begin to fall asleep. I feel a heaviness in my lungs. It becomes difficult to breathe and I already know that this is the cue that introduces the state of kanashibari, and that soon I will meet a dream that will be both horrifying and strange, and that will leave me immobile. The dream is sound—the sound of a woman’s voice calling from the wall to my left. It roars like a sea I have never heard of before. Not the Pacific Ocean. Perhaps the Japan Sea. It roars and tumbles through the plaster wall, breaking down any wooden beams. Smelling of mothballs and old things. I wake up startled. It is still the dead of night. I am in Koganecho and there is a faint knock of knuckles at the door. A man is whistling. An alley cat cries. Could I still be dreaming? There is a summer veil of humidity like a dampness stuck to my skin, a haunting that is heavy. It is alive in this apartment. Like the dream of the ocean, it beckons me to listen.

Figure 3. Port of Dream (2014), Cindy Mochizuki. Koganecho Art Bazaar, Fictive Communities Asia, 2014. Koganecho, Yokohama, Japan. Curated by Hakiko Hara. Photo courtesy of Koganecho Art Bazaar.

2. I remember being one of the four artists to arrive relatively early to the residency, and I remember walking along a dark alleyway to my small accommodation. I shake hands with now-friends Zeus Bascon, Paul Mundok, and Walter Scott in the alley. None of them are staying near me. Everything feels farther away in my mind, but later I discover they were always within walking distance. The studios and the apartments at Koganecho were one of 150 tiny chon-no-ma (one-woman brothels) that filled the red-light district alongside the Ooka River during the American occupation in World War Two and during the turn of the twenty-first century, as late as 2005. Perhaps this is the unspoken haunting that I feel. And this silence becomes a point of conversation among some of the other foreign artists—the specter that haunts space. The strange sightings of figures floating on by. What might it mean to be making art on this land, and in this contested space, as guests from other countries? How do we make work in conversation with unspoken, though not unspeaking, ghosts?

Figure 4. Port of Dream (2014), Cindy Mochizuki. Koganecho Art Bazaar, Fictive Communities Asia, 2014. Koganecho, Yokohama, Japan. Curated by Hakiko Hara. Photo courtesy of Koganecho Art Bazaar.

On this trip to Japan, I travel with my seventy-two-year-old mother, who hasn’t been back to the motherland in ten years. She tells me she hasn’t been back here since the passing of her mother in Yokohoma. It has taken ten years and the death of my father in 2013 to make a return back to this place. On the plane ride, she tells me of her teenage memories of the meaning of Koganecho. Of young women who disappeared and never came back to school after visiting Koganecho, of the American soldiers, of the American B29 that bombed the train station, of the ghosts buried at the site. She says the bodies lie in the rocks, the stones of Koganecho. She looks at me with wide eyes. Maybe this is the cause of kanashibari tonight. We part ways at Haneda Airport and she stays with my brother and heads to Shin-Sugita which is a few train stations away from Koganecho, I discover.

Figure 5. Fortune House (2014), Cindy Mochizuki. Koganecho Art Bazaar, Fictive Communities Asia, 2014. Koganecho, Yokohama, Japan. Curated by Hakiko Hara. Photo courtesy of Koganecho Art Bazaar.

3. The film strip is 35mm and it is flickering past me, showing a tower and a small boy—my brother. My deceased maternal grandfather. My mother and her sister (my aunt), and my deceased father. He has dark side burns and hair. I don’t know him in this light. The boy is the reason they go back to Japan. Seconds into the film we see the Hikawa Maru docked at the shore.[5] A tourist site? I wonder. I bring it with me. A few days into the residency, the curator tells me that the Hikawa Maru exists now as a boat museum, and that the site is nearby—walking distance. I bring Naoki, the cinematographer, and we head to the site. Everything is still there but the people in the frame. I try to recreate the shots. My dad trying to catch and preserve each tourist site. He zooms in to catch focus. I hold the camera steady and get the footage of the boat sturdy and wide on the water. I carry the footage back. I look at both moving images back and forth in the studio. My editor and I piece together a film. We project it in the upper floor of my studio space. There is a ghost in the room that a child sees. A woman. I keep hearing a vacuum cleaner.

Figure 6. all your monsters (2014), Cindy Mochizuki. Koganecho Art Bazaar, Fictive Communities Asia, 2014. Koganecho, Yokohama, Japan. Curated by Hakiko Hara. Photo courtesy of Koganecho Art Bazaar.

In the lower space of the studio I read fortunes for weeks, for free. If you leave a monster story you can get a reading. It is sold out. Full. I work day in and day out reading for strangers I don’t know. We sit intimately alone in the cha no ma space. I have decorated it simply, with a table, two chairs, a miniature bonsai, a candle, and a crystal. Someone asks if there is another artist, a woman by the staircase. I turn around and no one is standing there. At the end of the reading, each participant is to leave behind a story about a monster or they can attempt to describe what monster means to them. The woman who brings her four-year-old daughter with her says, “A monster is juyo/important.” She goes on to describe her travels to places where the site will greet her by way of natural forces, or ghosts. Her daughter is not shielded from this ghost talk. In fact, as a mother, she says it’s important for her daughter’s young ears to know about this. The little girl turns the corner to my haunted staircase and begins to cry, pointing at nothing but the stairs. “What is it?” her mother asks, rushing to her side. “A ghost,” she says. She proceeds to tell us she accidentally swallowed it—breathed it in as she gulped for air between cries. Her mother without missing a beat exclaimed, “Well, then, cough it out.” She hits her daughter’s back lightly and motions a ghost jumping out of her mouth. “Done, it’s out.” They both thank me with a box of treats and leave. In that same corner a small shrine of hand-built monsters begins to form, a means of processing the memory work of what just happened. Like a plate of ash and decay, figures form faces in the clay. A cluster of ghosts, living and breathing.

Figure 7. Loch/穴 (2014), Cindy Mochizuki. Phase 1 worskshop. Koganecho Art Bazaar, Fictive Communities Asia, 2014. Koganecho, Yokohama, Japan. Curated by Makiko Hara. Photo courtesy of Paul Mundok.

4. My aunt lives in the old house in Shin-Sugita—the old house wasn’t earthquake proof, and the sealed house stands on the property like a living object from the war times. A house made for Americans, it is the only Western house in the neighborhood. My aunt plays the piano and begins to play an old childhood song and my mother sits down beside her and they play together. My aunt is more confident with the keys, playing and composing and teaching music all her life. My mother, I feel, won’t know what to do. Her fingers, nimble as they are from making tiny dolls in her senior crafting class on Friday mornings, may not know. Do they remember how to play? To that very day in 2014, I didn’t know she played piano. Or did she? Had she ever told me this? She doesn’t know how to play the piano. But she begins and she knows how to strike chords, add mood and depth, using her entire body to pull feeling into the press and release of keys. They play together as two siblings should. They speak without words but through the notes. Laughing and cheering each other on. This lull of back and forth is not quiet; it is loud, cacophonous, and beautiful. The entire house quakes again.

Figure 8. Loch/穴 (2014), Cindy Mochizuki. Phase 1 worskshop. Koganecho Art Bazaar, Fictive Communities Asia, 2014. Koganecho, Yokohama, Japan. Curated by Makiko Hara. Photo courtesy of Paul Mundok.

This is their first conversation after being away for so long. She who stays: a younger sister that stayed behind to care for an aging mother. She who goes: an older sister who crossed the Pacific Ocean to marry my father and start a new life. The older sister catches up now, picking up speed. The younger sister begins to cry with joy, clapping at her sister’s memory. They both cry and say at the end, “Now wasn’t that fun? It’s been a long time.” I ask if I can record them playing, and I capture the sounds of the room, their music, their distance and closeness like an ebb and flow of water. I am here beside the oceans that bring me close. I am floating between this side of the Pacific Ocean and that side. I am buoyed and carried to reach a new understanding of their relationship, and the seas.

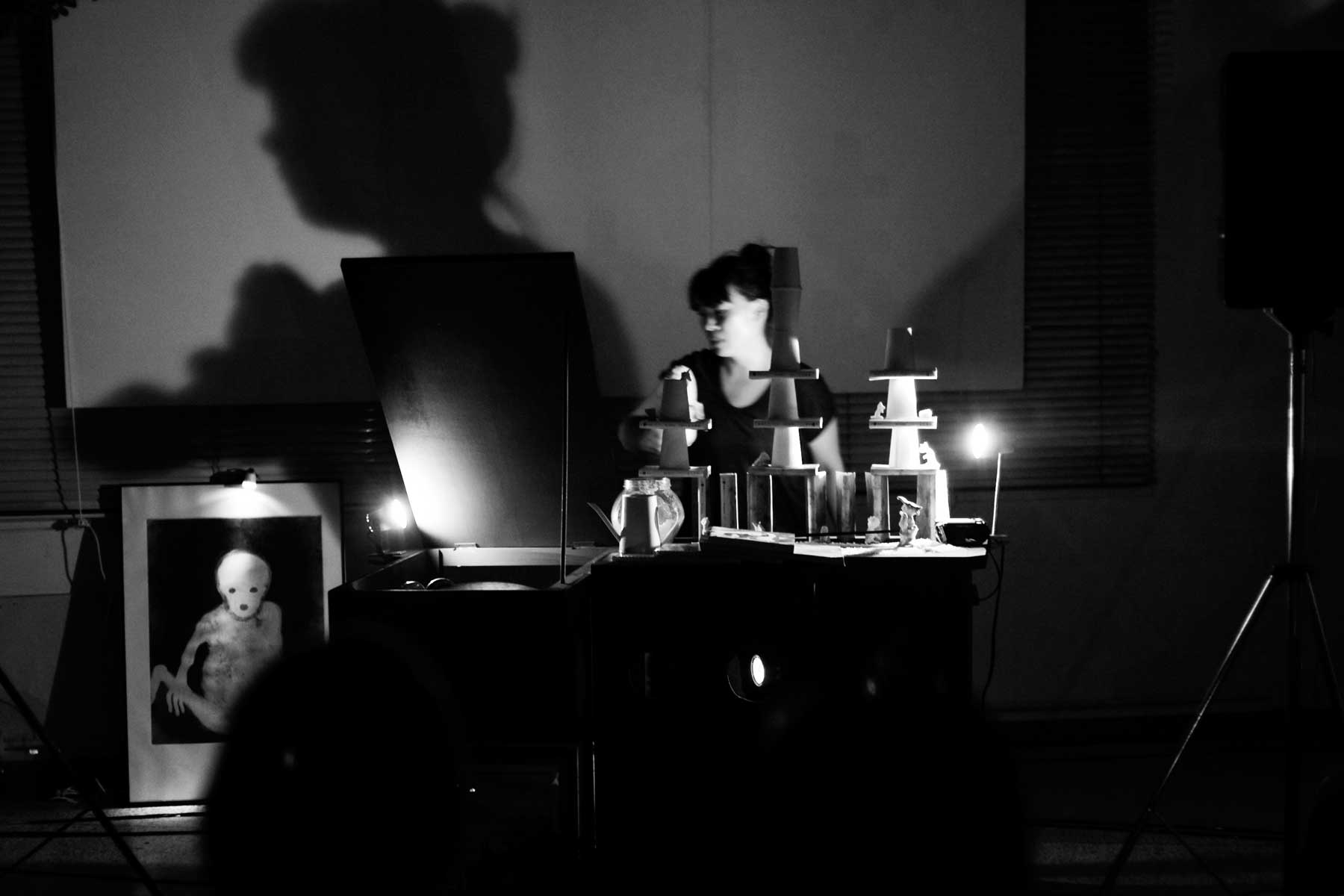

Figure 9. loch (2016), Cindy Mochizuki in collaboration with Emma Hendrix, directed by James Long. Moberly Arts Center, Vancouver, British Columbia. Co-presented by Mochizuki Studios, Moberly Arts Center, Theater Replacement, Vancouver New Music, and VIVO Media Arts Center. Photo by Paul Tim Matheson.

Figure 10. loch (2016), Cindy Mochizuki in collaboration with Emma Hendrix, directed by James Long. Moberly Arts Center, Vancouver, British Columbia. Co-presented by Mochizuki Studios, Moberly Arts Center, Theater Replacement, Vancouver New Music, and VIVO Media Arts Center. Photo by Paul Tim Matheson.

Notes

[1] Tyler Morgenstern, “Endurant Bodies/Atmospheric Borders: Race, Indigeneity and Transmedia Art in Contemporary Canada” (MA Thesis, Concordia University, 2015).

[2] Sunera Thobani, Exalted Subjects: Studies in the Making of Race and Nation in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007).

[3] Kanashibari is a common form of sleep paralysis in Japan.

[4] Fictive Communities was the theme of the 2014 residency at Koganecho curated by Makiko Hara. For more, see http://www.koganecho.net/koganecho-bazaar-2014/e-index.html

[5] The Hikawa Maru is a Japanese ocean liner launched in the 1930’s, that ran a route from Yokohama to Vancouver and Seattle.

Cindy Mochizuki is a Vancouver-based, multidisciplinary artist. She creates multi-media installations, performances, animations, drawings, and community-engaged projects that explore the ways in which we manifest story. Interested in the intersections of fiction and documentary, her projects are often site-specific and engage historical memory, displacement and the invisible. Her community-engaged projects explore the triangular relationship of performativity, social engagement, and magic. A large body of her work investigates narratives and memories within the archive of familial architecture, including childhood spaces, home videos, photography, and oral histories. These projects revisit the memory and history of displacement and migration of family members both within Canada and Japan. She has screened and exhibited her work both nationally and internationally. Cindy received her MFA in Interdisciplinary Studies from the School for Contemporary Arts at Simon Fraser University.