The Karrabing Film Collective: “Talking Back” to Ethnographic Media and Mineral Extraction in Australia

Saturday, February 29, 2020 at 8:51PM

Saturday, February 29, 2020 at 8:51PM Maggie Wander

[ PDF Version ]

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are advised that the following essay contains images of deceased persons.

The Karrabing Film Collective is a group of about thirty Indigenous Australians and their close colleague Elizabeth Povinelli, an American anthropologist. Since establishing themselves in 2007, the collective’s films have been increasingly screened and exhibited at an international scale.[1] Each of their films focuses on everyday issues the collective members face as Indigenous Australians living in the Northern Territory today: youth incarceration, poverty, the imposition of mining on traditional lands, local responsibilities to ancestors, and navigating the bureaucracy of the nation-state. Although the narratives are based on their real-life experiences, Karrabing’s films are not ethnographic; they are not documentary films that provide “truthful” or “objective” windows onto the worlds of “non-Western” peoples. In fact, their films deliberately subvert modes by which Indigenous cultures have historically been (mis)represented on screen.[2] This essay focuses on two of their films, Windjarrameru: The Stealing C*nt$ (dir. Elizabeth Povellini, Australia, 2015) and The Mermaids, Or Aiden in Wonderland (dir. Elizabeth Povellini, Australia, 2018), as well as the two-channel installation version of The Mermaids titled Mermaids: Mirror Worlds (2018). Both films and the installation make reference to the exploitation of Indigenous bodies and lands in colonial media practices. What I find most compelling about Karrabing’s films, however, is the way they relate these exploitative media representations to the legacy of mining on Indigenous lands, calling attention to the way contemporary landscapes of resource extraction use the same representational modes as ethnographic media during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Karrabing thus exemplifies what Faye Ginsburg has termed “cultural activism,” in which “the media being produced by indigenous, diaspora, and other media makers challenge a long-outdated paradigm of ethnographic film built on notions of culture as a stable and bounded object, documentary representation as restricted to realist illusion, and media technologies as inescapable agents of western imperialism.”[3]

Filmmaking is a particularly effective medium by which to challenge colonial structures of power because it has historically been used as a tool for subjugating Indigenous populations. Since its advent in the nineteenth century, photography (and later film) was considered the key to depicting true, unmediated, and unbiased representations of reality. Photographic and filmic images were thus seen as scientific tools for the production and dissemination of knowledge about “exotic” peoples and places that were increasingly coming under colonial rule in the second half of the nineteenth century. Postcards and advertisements circulated to attract popular interest in newly colonized territories, while images of racialized bodies became the standard mode by which the pseudoscience of anthropometry proved nonwhite bodies to be inferior to their white counterparts. This representational practice was standardized from the 1860s to 90s by individuals like Thomas Huxley, whose photometric system created the illusion that racial difference could be reliably recorded on camera.[4]

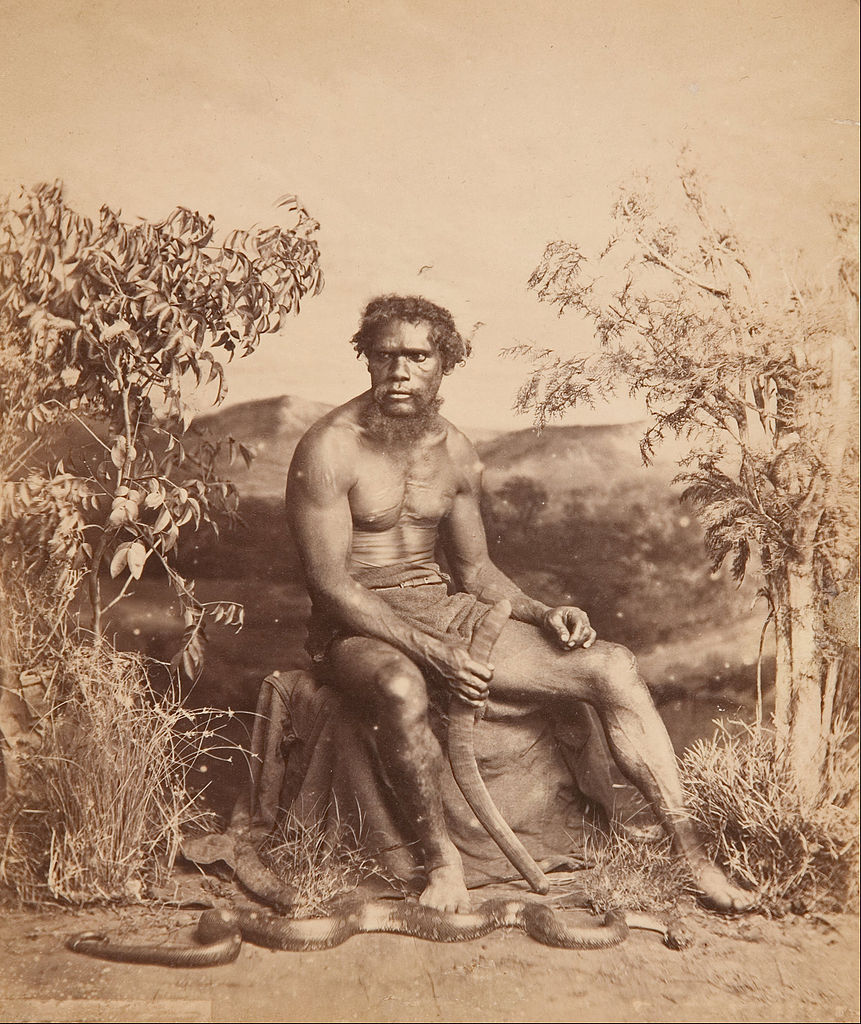

Photography became a tool for the emerging discipline of anthropology in the second half of the nineteenth century. Not only did the medium support contemporaneous racial theories, but it also enabled anthropologists to document what they considered to be dying races. The figure of the dying native appears in popular imagery of British settlements, implying the Australian landscape would soon be empty of Indigenous occupants and thereby paving the way for settler expansion. This ‘salvage’ photography often framed Indigenous individuals—rather than family units—as unthreatening and weak. In such images, lone Indigenous figures might be sitting or reclining, as if they have no energy to stand. They would be surrounded by material culture that came to signify backward technologies such as spears, minimalist shelters, net bags. The spears and other weapons would often be shown resting against a wall nearby or loosely grasped by an individual. The studio portraits of John William Lindt in the 1870s and the outdoor scenes by Thomas Dick in the early 1900s provide examples of these conventions (fig. 1).

Figure 1. John William Lindt, Portrait of an Aboriginal Man, c. 1873-1874, Google Arts & Culture, artsandculture.google.com/asset/portrait-of-an-aboriginal-man-j-w-lindt/zQHweJCWC2bJwg (accessed 4 May 2019).

Such standards continued into the twentieth century when ethnographic cinema gained popularity among the wider public. Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (USA, 1922) and Moana (USA, 1926) are common examples of how these conventions appeared in film. The popular medium further normalized colonial depictions of Indigenous populations. In these two films, for instance, there is no sign of settler colonial culture and the subjects direct their attention away from the camera, creating the illusion of a candid, and therefore authentic, moment. Such a move exemplifies a type of “observational cinema,” described by David MacDougall, in which the narrative is told from the third-person, the camera is detached, and the filmmaker is invisible. When used in ethnographic studies, according to MacDougall, such a strategy “inevitably reaffirm[s] the colonial origins of anthropology. It was once the European who decided what was worth knowing about ‘primitive’ peoples and what they in turn should be taught. . . . The traditions of science and narrative art combine in this instance to dehumanize the study of humanity.”[5]

By the late twentieth century, Indigenous artists across the globe took the camera into their own hands to reverse that colonial gaze. Well-known examples include the Kayapo in Brazil, who recorded their own communities on film and established a radio network in the late 1960s. They too used film as a form of cultural activism, strategically documenting and disseminating their fight against the Xingu Dam Project at Altamira in 1989.[6] Indigenous media in Australia share a similar history in that critical radio and television projects emerged in the West Desert and the Northern Territory in the 1970s. Films were later made in collaboration with anthropologists, complicating the authoritative relationship between filmmakers and their interlocutors. For example, Two Laws (dir. Carolyn Strachann and Alessandro Calvidini, Australia, 1981) was a collaborative project in which a community from Borroloola in the Northern Territory told the history of Indigenous land rights through reenactments and interviews.

The Karrabing Film Collective is thus part of a long tradition of “talking back,” to use the words of Faye Ginsburg, “to and through the categories that have been created to contain indigenous people.”[7] Karrabing is also part of a new generation of artists who are creatively building on the legacy of Indigenous media by visually quoting colonial film and photography. For instance, ARTICNOISE (2015) was an exhibition by Geronimo Inutiq that came out of the artist’s residency at the National Gallery of Canada. The National Gallery houses the archive of Igloolik Isuma Productions Inc., Canada’s first Inuit production company that rose to prominence when their feature film Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (dir. Zacharias Kunuk, Canada, 2001) won the Caméra d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. For ARTICNOISE, Inutiq remixed the archival collection of Igloolik Isuma’s repertoire by combining it with footage from Glenn Gould’s radio documentary The Idea of North (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation,1967). In Gould’s documentary, Indigenous land becomes a desolate, isolated space, “an open expanse of snow and ice ready for the projection of a colonial imaginary.”[8] ARTICNOISE combines audio from The Idea of North with footage from the Igloolik Isuma archive, challenging colonial visions of Indigenous lands and building on the long history of cultural activism that media projects in settled lands have achieved.

Karrabing also uses this kind of visual quotation, and like Inutiq with Glenn Gould, Karrabing quotes the very colonial imagery they are subverting. One example is the opening scene of their 2015 film Windjarrameru: The Stealing C*nt$. The film follows a group of young men who discover a carton of beer in the bush. As they drink, their voices become louder, they start having more fun, they become a little rowdy, and then they begin arguing with two older men nearby. It turns out these two men work for a mining company, and they are illegally prospecting at a sacred site.[9] Eventually the older men call the police, who falsely accuse the young men of stealing the beer and chase the young men into a marsh that has been marked off as a toxic area because of nearby mining activity.

Figure 2. Still image from The Karrabing Film Collective’s Windjarrameru: The Stealing C*nt$.

The film begins with black-and-white footage of the two older men sitting by a rock wall on the water’s edge (fig. 2). One of them begins to paint a large circle on the rock, while a voice-over explains to the audience: “Tonight, we bring you one of the strangest and most dramatic aspects of life in this wide land of ours.” The narrator goes on to describe a “remarkable ceremony” in which Indigenous people dance, sing, and play the didgeridoo. The audio clip is taken from a 1958 television show called Australian Walkabout (dir. Charles Chauvel, BBC), a popular documentary series that exemplifies many of the ethnographic conventions of late nineteenth century photography and film. By pairing this voice-over with the footage of a man producing rock art, Karrabing gestures to the history of ethnographic documentary that has shaped the public imagination of Indigenous Australian life.[10]

As the opening credits appear on the screen, the narrator continues to describe the ceremony: “an uncle is moving around, beating himself on the head.” Suddenly, the scene cuts to a contemporary, color view of Darwin, Australia, in which a young Indigenous man takes selfies on his iPhone as the audience hears the sound of airplanes overhead. The camera soon returns to the painter from the opening scene who interrupts his work to ask his companion, “How do you spell ‘blasting?’” He begins writing “B-L-A-” in the center of the painted circle before the young men begin heckling them with beer cans. We later learn the older man and his companion work for a mining company and are illegally prospecting for drilling sites (fig. 3). The narration thus comes into tension with the contemporary world of resource extraction, subverting audience expectations of witnessing a pristine, pre-contact world.

Figure 3. Still image from The Karrabing Film Collective’s Windjarrameru: The Stealing C*nt$.

When the two men in this opening scene are revealed to be mining employees rather than ethnographic subjects, Karrabing actors are “refus[ing] to play the part they ha[ve] been assigned. They refus[e] to function as a past-oriented and changeless object, a trace of something before the savage assault of settler colonialism.”[11] In their films, not only do Karrabing members refuse to fall into the trope of Indigeneity that is perpetuated by ethnographic film and photography, they also make visible the violence of colonialism that is usually left out of the frame. John William Lindt’s studio photography, for example, does not show the bags of flour that were laced with arsenic and traded to Indigenous Australians, nor does it depict the crowded and underserved communities that formed around mining towns as Indigenous people were forced off their land to make way for settlements and pastoralism.[12]

In The Mermaids, Or Aiden in Wonderland, such violence is made visible by the dystopic landscape in which the film is set. The world has become toxic for the white population, and they cannot go outside without oxygen masks and hazmat suits. In search of a cure, white survivors conduct experiments on Indigenous Australians, who can survive in the toxic wasteland. They coerce the “mermaids”—a group of female beings who live near a watering hole—to steal Indigenous children, who are then subjected to experiments in which their bodies are violently injected with plastic tubes that presumably extract substances to be used in experiments.

For viewers familiar with the colonial history of Australia, the film’s plot might remind them of the violent and traumatic history of Indigenous child removal. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Australian government segregated Indigenous children in settlements, missions, and state institutions, justifying this practice as a form of protection for Indigenous communities suffering from increasing displacement, disease, and poverty. Like the Indian residential schools in North America, children at these institutions were subjected to brutal systems of cultural suppression and bodily harm.[13] Now referred to as the “stolen generation,” these children and their descendants continue to fight for public recognition of this violent colonial practice. The Mermaids relates this history to continuing colonial practices of ecological destruction because children are targeted (and extracted) by the white population for experiments aimed at finding a cure for white people to survive in the toxic outdoors— toxicity which is the result of the very actions by that same white population.[14]

Figure 4. Still image from The Karrabing Film Collective’s The Mermaids, Or Aiden in Wonderland.

Toward the end of the film, we are taken to the “mud place” where the children are imprisoned (fig. 4). Long plastic tubes converge in a muddy stream, disappearing into the ground, while a group of children stands in a circle holding the other end of the tubes to their faces. Adults dressed in protective jumpsuits and masks—the white scientists—poke the children with long sticks in fear of contamination. In a later scene, we see two of the children lying in the ground, covered in mud and visibly struggling to break free from the tubes that are inserted into their bodies (fig. 5).

Figure 5. Still image from The Karrabing Film Collective’s The Mermaids, Or Aiden in Wonderland.

As in Windjarrameru, Karrabing references the way colonial cultures extract and exploit Indigenous bodies and lands. However, this time, rather than subverting depictions of Indigenous Australians as timeless, exotic, and untouched by colonial culture, The Mermaids subverts images of Indigenous Australians as scientific proof of racial difference and, by extension, of racial hierarchies. In Thomas Huxley’s anthropometric photographs, for example, Indigenous specimens are placed in a studio devoid of any signs of colonial violence. By showing the children thrashing around in the mud and being forced to hold tubes to their mouths, Karrabing makes the violence of these scientific studies visible in ways that were erased or left out of the frames in anthropometric images of Indigenous people being measured against yardsticks.

Furthermore, Karrabing directly connects historical representations of Indigenous Australians in colonial film and photography to contemporary practices that continue to exploit Indigenous bodies and lands. Mermaids: Mirror Worlds, a two-channel video installation, is an especially poignant instance in making these connections apparent. In this installation, The Mermaids film discussed above is shown on the right screen, while the left screen occasionally lights up with footage ranging from news media about mining equipment to television documentaries produced by companies such as Monsanto and Dow. In one such “mirror world,” as these interludes are called, we see an extract from a video by The Economist on deep-sea mining technologies. The footage shows massive vehicles with long appendages that end in spinning metal discs with claw-like spikes. The narrator explains this technology has immense potential to generate wealth: “With an estimated 150 trillion dollars’ worth of gold alone, deep sea mining has the potential to transform the global economy.”

The depiction of mining technologies as awe-inspiring, wealth-producing subjects in their own right has a long precedent in film and media about resource extraction. For instance, the same Walkabout series mentioned above features an episode about the Rum Jungle area near Darwin, where one of the first uranium mines in Australia was established in 1954. The narrator shines a positive light on the mining industry, saying that “most people think of bombs when they think of uranium, but today the accent is on energy and heat and medicine and agriculture.”[15] The camera focuses on the large machine digging into the mountainside, and the enormous shovel appears as a face, complete with sinister eyes and razor-sharp fangs. The narration reinforces this allusion by describing the machine as a “near-human monster with supernatural power.”

Figure 6. Still image from The Karrabing Film Collective, Mermaids: Mirror Worlds.

Mermaids: Mirror Worlds “talks back” to this kind of portrayal by reversing the camera to show settler cultures as the ones who are supernatural, exotic, and other-worldly. When the left-hand channel shows clips from Australian and American media, the colors are distorted so the industrial tools glow in surreal tones of oranges and blues (fig. 6). People are washed out and their pupils are mere specks, turning them into ghost-like figures (fig. 7). Their voices are slowed down, and the pitch is much lower than the average human’s. Here, Karrabing reverses the gaze that frames Indigenous peoples as the “strangest and most dramatic aspects of life,” as in Windjarrameru’s satirical opening, and instead asks their audience to consider the bizarre logic that drives resource extraction for the sake of unequal economic gain. Again, Ginsburg describes this strategy in terms of cultural activism: “this reversal stands, metaphorically, for the ways in which indigenous people have been using the inscription of their screen memories in media to ‘talk back’ to structures of power and state that have denied their rights, subjectivity, and citizenship for over two hundred years.”[16]

Figure 7. Still image from The Karrabing Film Collective, Mermaids: Mirror Worlds.

The scenes discussed above are three examples of the way Karrabing uses the very tools of colonial power to make visible the overlapping forces of resource extraction and colonial imaging of Indigenous bodies and lands. Windjarrameru subverts audience expectations of timeless Indigenous life by transforming the two older men from ethnographic subjects to mining employees. The Mermaids frames the current (and future) toxic landscape produced by the mining industry as a continuation of the scientific exploitation of Indigenous bodies. And finally, Mermaids: Mirror Worlds reverses the camera’s gaze to render mineral extraction as the exotic Other. With these examples, I have argued Karrabing’s work sits in a longer history of Indigenous media and cultural activism. There is more to be discovered, however, in the ways Karrabing’s films problematize what is considered to be an Indigenous experience in the first place and what counts as media in today’s world.

Acknowledgments: The author wishes to thank Professor Stacy Kamehiro and anonymous peer reviewers for their feedback on early drafts of this paper, and Professor Elizabeth Povinelli for generously granting access to view the films. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the College Art Association conference in New York City in 2017, which was made possible by the Arts Dean’s Fund for Excellence at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Notes

[1] This includes international film festivals, arts exhibitions, and gallery installations such as: Berlinale Film Festival, Melbourne International Film Festival, Contour Biennale in Mechelen Oslo National Academy of Arts, Institute of Modern Art at Brisbane, Tate Modern, documenta 14, Centre Pompidou, Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art 9, and most recently a solo exhibition at MoMA PS1 in New York City. In 2015 they received the Visible Award for socially engaged contemporary art practice as well as the Nova Award for Best Short Fiction Film.

[2] It is important to note, however, that Karrabing “members have never positioned their work as the empowered solution to issues of anthropological voice.” Elizabeth Povinelli and Tess Lea, “Karrabing: An Essay in Keywords,” Visual Anthropology Review 34, no. 1 (2018): 41. The subversion to which I am referring is rather a mode of exploring what it means to be Indigenous in the Australian settler state, and engaging with colonial modes of representation is one part of this process. Furthermore, Karrabing never claim to be representing all Indigenous Australians, especially because, as scholars such as Marcia Langton have argued, the notion of one authentic representation is a colonial myth. Marcia Langton, ‘Well, I heard it on the radio and I saw it on the television…’: An Essay for the Australian Film Commission on the Politics and Aesthetics of Filmmaking by and about Aboriginal People and Things (Woolloomooloo, NSW: Australian Film Commission, 1993), 27. Rather, Karrabing’s films are one means by which this group of individuals is navigating their specific circumstances in this specific moment.

[3] Faye Ginsburg, “Culture/Media: A (Mild) Polemic,” Anthropology Today 10, no. 2 (1994): 14.

[4] For an excellent discussion of Thomas Huxley, see Elizabeth Edwards’ chapter “Professor Huxley’s Well-considered Plan,” in Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology, and Museums (Oxford and New York: Berg, 2001), 131-156.

[5] David MacDougall, “Beyond Observational Cinema,” in Transcultural Cinema, ed. Lucien Taylor (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998), 133.

[6] Terence Turner, “The Social Dynamics of Video Media in an Indigenous Society,” Visual Anthropology Review 7, no. 2 (1991): 68–76, www.doi.org/10.1525/var.1991.7.2.68.

[7] Faye Ginsburg, “Screen Memories: Resignifying the Traditional in Indigenous Media,” Media Worlds: Anthropology in New Terrain, ed. Faye Ginsburg, Lila Abu-Lughod, and Brian Larkin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 51.

[8] Kate Hennessey, Trudi Lynn Smith, and Tarah Hogue, “ARCTICNOISE and Broadcasting Futures: Geronimo Inutiq Remixed the Igloolik Isuma Archive,” Cultural Anthropology 33, no. 2 (2018): 219, www.doi.org/10.14506/ca33.2.05.

[9] This scene reflects the current reality Aboriginal landowners face, for many mining corporations have destroyed sacred sites. One well-known example is Two Women Sitting Down, a sacred site near Bootu Creek in the Northern Territory that is owned by the Kunapa. In 2013, the Kunapa sued OM Manganese, a large mining corporation that was leasing land at Bootu Creek, for damaging a rock formation at Two Women Sitting Down. The BBC cites this lawsuit as “the first time a company has been successfully prosecuted in Australia for desecration of a sacred site” and the company was made to pay $150,000 in fees. “Mining Firm Desecrated Australia Aboriginal Site,” BBC News, 2 August 2013, www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-23527303.

[10] The Australian Walkabout series they use, for example, was a popular television show for the Australian public in 1958. It featured 13 episodes that chronicled the adventures of Charles and Elsa Chauvel through the Australian outback, including their ‘encounters’ with Indigenous communities.

[11] Elizabeth Povinelli, Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 82.

[12] Fiona Foley, a contemporary Indigenous Australian artist, repeatedly refers to the practice of lacing flour with arsenic and then trading it to Indigenous landowners in her installations Land Deal (1995) and Velvet waters – laced flour (1966). For more information on Indigenous settlements that emerged in the wake of mining and pastoralism in early Australian history, see Penelope Edmonds, Urbanizing Frontiers (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2010); Tracey Banivanua-Mar and Penelope Edmonds, eds, Making Settler Colonial Space (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010); and Benedict Scambary, My Country, Mine Country (Canberra: Australian National University Press, 2013).

[13] For an excellent comparative history of Indigenous child removal policies in Australia and North America, see Margaret Jacobs, White Mother to a Dark Race (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011).

[14] One instance in which Karrabing implies it is the extractive practices by the white population who made the landscape toxic is when a young child is traveling through the bush with a mermaid, and fire erupts around him, smoke consuming the sky. Commenting on the size and severity of the fire, the boy asks, “From that fracking, or what?” He wonders what the land was like before this destruction, and the mermaid responds, “Before white people came, the world was alright.”

[15] “Rum Jungle,” episode of Australian Walkabout, dir. Charles Chauvel, writ. Charles Chauvel and Elsa Chauvel, BBC, 1958.

[16] Ginsburg, “Screen Memories,” 51.

Maggie Wander is a PhD Candidate in Visual Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her dissertation project looks at contemporary artists in Oceania who interrogate the representation of colonized peoples and places of the region in the context of ecological devastation. She has presented her work internationally at conferences including the College Art Association and the European Society of Oceanists. Her writing has been published in The Contemporary Pacific and Commonwealth Essays and Studies. Maggie is also the Managing Editor of Refract: An Open Access Visual Studies Journal.