Corvid Emoji Needed

Saturday, May 29, 2021 at 12:40PM

Saturday, May 29, 2021 at 12:40PM Paige Sarlin

[ PDF Version ]

Adrian died from a heroin overdose in March 2020. One week into Coronavirus social distancing, his mother couldn’t arrange a funeral—Tori couldn’t receive guests in her home. I couldn’t fly to Providence to sit with my friend and weep.

Tori needs a crow emoji. Actually, my friend needs a wake of crows similar to those bursts of hearts or confetti that explode when you text ‘congrats’ these days. The crows need to be able to fly across the screen and out of the phone’s frame.

Tori doesn’t need a real crow—I don’t want for her to have to do an image search, to box one in with a snapshot’s frame. It needs to be an emoji. Ready to hand (or finger, rather)—one or two quick taps away from flight. She and I both need a digital character to help index and mediate the ebb and flow of mourning—a sign to mark the connection between the internal states and external worlds that we share.

I’d spoken with Tori the week before her son died. But it was almost two months after he died before I heard her voice again—before she called. Having “lost” my husband 4 years ago, I know how hard it is to talk on the phone when one is deep in grief. Experiencing the death of someone so close, so dear, is tremendously exhausting, and talking often feels impossible. So we text.

In April (what felt like five years later), I sent her screenshots with a brilliant parable about a crow from Max Porter’s novel Grief is the Thing with Feathers.[1] In response to the tale of a crow that protects a family from a grief-eating demon, she wanted to send me a crow. She couldn’t find one in her phone’s standard cache. She refused to settle for the bald eagle with its talons and white head. The symbol she wanted to send needed to be all black—a raven’s silhouette.

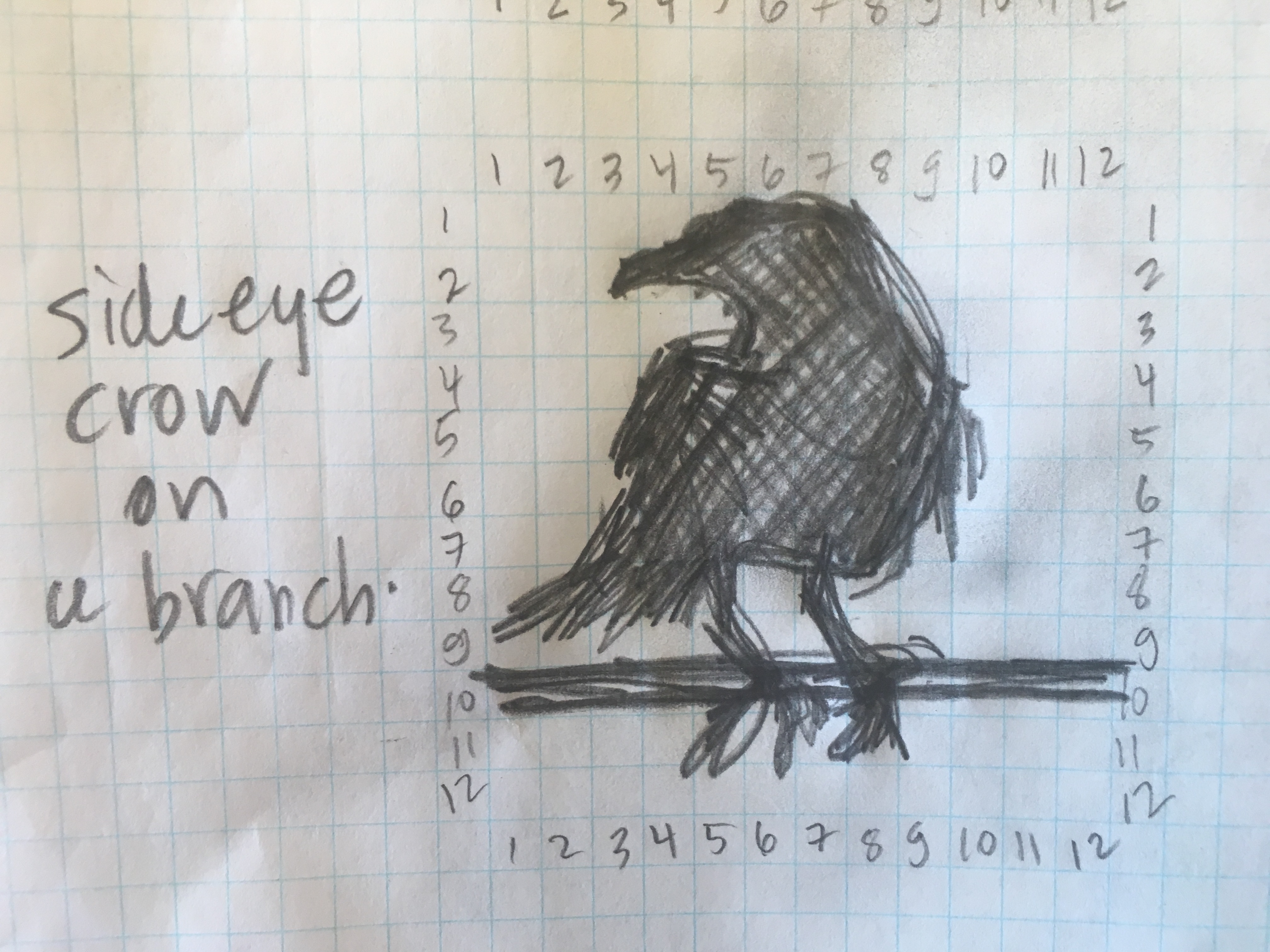

Figure 1. Crow silhouette.

A duck, an owl, a rooster, and a hatching chick appear in every emoji line-up, but no black bird is recognized across all platforms and software. There is no stately fowl to punctuate complaints. No shadow figures on a branch, no preening mates. The digital landscape needs at least one solemn symbol to supplement the peaceful dove and that benighted bluebird cutout. Ideally, there would be a corvid set: a side-eye squawker, a solitary witness on a line, and one raven in full flight. It could inaugurate a collection of more pointed signs beside the circle with a smile.

Corvus is the name of the family of birds that include ravens, jays, rooks, and crows. They exist on every continent except South America and Antarctica. All but extinct or endangered on some islands (Hawai‘i and the Mariana Islands), they’ve overrun cities like Tokyo. Making their way into imaginations across the histories of culture, they appear in poetry, films, mythology, and art. Corvids terrorize, annoy, and fascinate. Known for being highly social and tremendously talkative, they gather and chatter. Considered one of the most “intelligent” of animals, their brains have been studied and their behaviors analyzed.[2] The object of both popular and scholarly writing, they are much adapted to their lives with humans. Stories and studies have documented that crows have the capacity to identify specific humans and respond to our behavior.[3] But our attunement to the crow is usually more poetic and less acute. The symbolism attributed to corvids skews towards the negative, but their cultural and literary associations are legion and varied. In contrast to the colonial and continental gothic, ravens are considered a harbinger of good luck for the Lenape tribe of Native Americans. Omnivores, there is no distinction in appearance between sexes. Crows mate for life.[4]

But it’s the accounts of their apparent capacity to mourn that reinforces the increased significance of the corvid as a symbol for the contemporary moment.[5] Crows attend to their dead in ways that seem to function like funerals—they gather around their fallen comrades, coming close to inspect a corpse, only to fly back to their congregations. Research has established that these gatherings have an epidemiological function, first and foremost.[6] They gather around their dead to establish the cause of death and assess the danger to the mob. Was it predator or poison, accident or murder? In the present conjuncture, these bird gatherings seem an even more appropriate reminder: A congress of crows doesn’t just look like a funeral—the social convention is a matter of public health. Detectives and contact-tracers, they gather for the safety of their community—an image-expression of social solidarity. To some degree, the attraction to corvids is and has always been to center, understand, or symbolize aspects of human feeling and experience. But the particularity, peculiarities, and ultimately the opacity of these birds and the ways in which they watch us as much as we watch them, makes the prospect of their addition to the digital vernacular feel quite timely.

Covid-19 has radically transformed the ways we attend to the dying and the dead, to death and its aftermaths. When I began to write this, there were no funerals held graveside or bedside family vigils. Months later, all of our death-related gatherings are still altered by caution and risk, masks, travel bans, and social distancing. Funerals and memorials look different worldwide. Held online, the ordinary rituals of dying and mourning are enabled by the most technical of service providers. Quarantine and isolation have imposed a cruel new distance. Thwarted in most attempts to be there to comfort people sick with grief, addiction or coronavirus, we are confronted with the limitations of our technical devices and the stark disparities and contradictions that shape the digital landscape. We need more carriers for grief, markers and signs for sorrow. We need ways to pay respect and attend to life, to emote, communicate, and connect in the aftermath. We need a new category of grief-related emoji to bear sadness and the deadly repetitions of loss. Tiny frowns, crying faces, and hearts are inadequate. We need a wake of corvids.

Emoji are a relatively recent addition to the digital lexicon, having been introduced in the 1990s as a group of animated pictographs available on specific phone carriers in Japan.[7] Following the popularity of these symbols, other platforms and operating systems developed their own graphic characters. In order to enable sharing and compatibility across platforms and between devices, a standard set of characters were codified and incorporated into Unicode in 2009. Since then, the number of emoji assigned unique numerical markers and labels with Unicode has grown, as have the various proprietary "skins:" the copyrighted visual renderings of the symbols that are distinct to each operating system or platform. Emoji have become a digital vernacular used to convey emotional nuance, inflection, and "color" in and across all forms of digital communication and messaging. As Unicode itself explains, "Emoji are very different from most other characters including regular pictographic characters. They are colorful, playful representations of persons, places, or things."[8] Naturalized as a form of visual language, the crying face emoji has even made its way into the Oxford English Dictionary as word of the year in 2015. Approximately seventy proposals for new characters are accepted and incorporated into each year’s Unicode update.[9] As Bethany Berard and others have detailed, the proposal process has standardized as the selection criteria for specific emoji characters have shifted over time.[10] But one factor that hasn’t changed is that once a character is accepted and included, it’s part of Unicode forever.[11]

Jenny Stinehour, a sixteen-year-old high-school student from Texas, submitted a proposal for a crow emoji in May 2019. The proposal L2/19-307 has begun to wind its way through the consortium’s vetting process, and the crow emoji is now an official "candidate" for encoding.[12] The corvid is now in the queue to be accepted by the voting members of the Unicode Consortium. To some extent, it feels like a no-brainer that the crow would be part of the universally available line-up. It so clearly meets the most important criteria: it has a distinctive appearance that can be rendered in myriad ways. As a result, the emoji will be both recognizable across platforms and extremely versatile, drawing on a tremendous diversity of associations appropriate to use in countless contexts. Situated outside the causal relation of the indexical vector but fully boxed within social, cultural, technical, and economic conventions, the crow emoji that Stinehour imagines and proposes will be iconic and symbolic—connected to “the natural world” (the phrase she uses) through resemblance, but separate from it, immune to the changes and threats it contains. Stinehour’s proposed emoji will refer to two species of birds, the raven and the crow, inscribing a common confusion that is so basic it is practically universal. Stinehour’s proposal makes this generic indeterminacy a virtue—that is, the emoji will stand for both, being neither exclusively. In her proposal, Stinehour argues this will make the emoji unique amongst existing animal emoji which refer to individual species. She makes of the apparent interchangeability and false equivalence between ravens and crows into a selling point, a point that becomes even more symbolic when you consider that there is no visual distinction in appearance between male and female corvids either.

It’s quite easy to imagine how technologically and culturally encoded black birds will find their way into threads and updates, volleys and exchanges, conversations and announcements. But the process will take time. Due to Coronavirus disruptions, the consortium won’t be voting on new emojis or releasing version 14.0 of the Unicode Standard until September 2021.[13] And after that, if they are selected, it will be at least another two years before everyone with a smart device or email will be able to see and send these birds. At that point, a new life for corvids as both cultural symbol and technical character will begin and stretch beyond the current idioms that indicate a direct path (“as the crow flies”) or evidence of aging (“the dreaded crow’s feet”). Statements like “Call me, I need to crow about something,” “you with your raven hair,” and “Eat crow, jerk” will be rendered with more efficiency. But maybe they will come to symbolize some of our newest normal practices—three crows together could signify an online meeting, a congregation of digital witnesses. After they are let loose, there will be no way to control the uses to which they are put or the meanings they conjure. It will be impossible to inoculate the figure of the crow from its historical role in naming the set of laws that enshrined segregation and white supremacy in the US. But perhaps it’s precisely that history that will enable them to become a mascot for unmasking what Ruha Benjamin calls the “New Jim Code,” the ways in which the logic of white supremacy is encoded into digital structures and designs that aim to undo racial disparity and discrimination.[14] Or perhaps they will accompany the clarion calls to fight against the attempts to bring back Jim Crow-style voter suppression across the United States.[15] Sent to lawmakers, strings of corvid emoji could indicate that people are watching and ready to swarm the streets and Twitter feeds.

In the wake of Covid-19 and the ever-increasing visibility of white supremacy and police violence, a crow emoji could function as a different kind of mediator or symbol—a carrier for sentiments, ideas, and energies that exceed the affordances of the characters we have. The introduction of a Unicode raven silhouette makes space for imagining an antidote to what Marina Magloire refers to as "White Condolences," the performative gestures which have proliferated with "the sudden attention to the ongoing grief of black life."[16] For Magloire, the recent trend of “hushed and tentative” statements made by white people do more to inscribe the distance and disconnect between the sender and recipient, between the newly awakened and the affected. As Magloire explains, the experience of grief is in no way universal, but perhaps the appearance of corvid emoji could acknowledge the inadequacy of language and the chasms of difference and disparity. Flying between us, digitally-rendered crows won’t diminish any loss or pain, but they might evoke a longer timeline in our instant messages. Replacing trite sentiments, they could punctuate the cruel and relentless duration of bereavement and invoke a desire to confront the long durée of death and injustice. Of course, some marketing department won’t be able to resist naming the new product group “A Murder of Crows.” But I prefer to borrow Thomas van Dooren’s notion of “a Wake of Crows” because it centers our attention on the communal nature of rituals associated with mourning, the way loss shapes the life cycles of birds and people, and how crucial metaphors and symbols of movement, social connection, and collective formations are in the face of grief and the threats of extinction, isolation, and immobility.[17]

Van Dooren’s book is part of a larger effort to challenge the negative associations with crows, to rehabilitate corvids and our images of these black birds as scavengers and interlopers, pests and antagonists. I’m thinking that we’re at a moment when marshalling the opacity of their silhouettes and their dark associations might help challenge what Christina Sharpe calls the “deathly order” of our moment, tied as it is to the “climate” and legacies of anti-Blackness and slavery and racial capitalism and environmental destruction, social crises that preceded this moment.[18] Statistically speaking, more people in the world are mourning than have died. For every loss, there are people added to an untallied roster, a new demographic without a metric, unfathomable and unrepresentable by any chart or graph—unavailable to enumerate or even calculate. Our lexicon of online visuals expands for them and the ring around them, too. The world is reckoning with mass numbers of deaths—deaths that have disproportionately impacted Black and Brown communities in the US and vulnerable populations all over the world. Daily increases across all three registers, from the virus, to police violence, to suicide and overdose, means that we encounter heartbreaking statistics regularly. These will continue to increase as the impact of mass unemployment, food insecurity, and poverty manifest. As death tolls continue to grow, mass graves are dug to receive bodies from the make-shift morgues, and newspapers are overrun with obituaries. Amidst this tremendous volume, most specific losses have garnered only moments of acknowledgement—scant space on news and social media platforms. The rest have been left to the private space. And all the while, the tolls increase. The singularity of any one loss is mourned off most screens. Counting is now epidemic.

The murder of George Floyd and the protests, marches, and uprisings that followed have resuscitated acts of public and communal mourning. This widespread anger and grief have since demanded both attention and response from every sector of society. It has taken cellphone video and feet on the ground to hold up individual names to mourn. Alongside the need to say each name and to inscribe Breonna Taylor, Daniel Prude, and Ahmaud Arbery into living memory, there’s a place for a different accounting, a new register of image, mark, and symbol to mediate the pain and rage, to share and mobilize the grief. The forms can’t just be idiosyncratic. They need to be available to travel between the intimate circuits and the complex structures that surround, enable, and shape them, the very systems that determine which lives matter and which deaths count.

There’s an absurdity in my suggestion that some tiny new symbols might ameliorate any of the pain associated with growing number of losses connected to drug addiction or suicide (what Anne Case and Angus Deaton call “deaths of despair”), coronavirus, inequality, or police violence.[19] But it’s the combination and contrast of these scales that I find so important: the ability of media forms to traverse these scapes, to move between, negotiate, and link distinct and discrete experiences, frameworks, and structures. With respect to emoji, the crow’s ability to fly between and across worlds seems relevant too.[20] Perhaps a certain kind of magic will be conjured by the deployment of the corvid’s graphic silhouette. As Luke Stark and Kate Crawford argue, “Emoji can deaden as well as enliven,” and perhaps it’s exactly that ambivalence that makes them so compelling as a medium in times of mourning.[21]

Arundhati Roy argues that the pandemic has opened up a "portal" through which to see how broken our systems are and to imagine how we might change and transform society.[22] But as the "deaths of despair" continue to increase, the pandemic has also opened up a portal through which to consider media’s capacity to mediate grief and isolation, to facilitate new processes of mourning. Stinehour’s proposal contributes to the development of images, vocabularies and symbols of exchange, but it can also be seen as part of an effort to imagine the development and codification of one particularly contemporary media form in the context of a conjuncture where bereavement and existence have been structurally imperiled. To draw from Sharpe again, "in the wake" of mass unemployment, public police lynching, anti-racist protests, and a hopelessly compromised health care system, the opportunity to supplement the arsenal of visual tools feels strangely concrete.[23] The pandemic has created an invitation to imagine, develop, and propose something that could signify the need for deeper and more sustainable forms of care, to contribute something much more than white condolences, thoughts and prayers, and empty corporate statements. I envision the corvid emoji conscripted into the broad “praxis of wake work” that Sharpe imagines and whose terrible urgency more people are confronting across platforms and geographies.[24] In this sense, these characters might be deployed to accompany the living through and with grief, threat, death, bereavement, and anger—to signal and signify the desire for otherwise worlds, to make room for the acts of imagination and defiance necessary to transform the destructive entanglements and craven denial that shapes the “unequal distribution of vulnerability” today.[25]

Figure 2. Crow sketch.

Coda

It’s been almost a year since this piece was first drafted—and the opportunities to imagine how a corvid emoji might be deployed have continued to multiply. More than mediators, their potential as reminders to stay vigilant seems as important as their status as digital markers of devasting losses. Summoned by a few taps on any smart phone, a wake of corvid emoji could signal a readiness to prevent death and not just mourn, to confront how grief’s expansive reach continues to change everything.

Notes

[1] Max Porter, Grief Is the Thing with Feathers: A Novel, (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2015). The excerpt I sent is published here: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/sep/12/max-porter-books-interview-grief-is-a-thing-with-feathers.

[2] The metrics used to assess the "intelligence" of crows have been defined in relation to human intelligence. My use of scare quotes here is meant to signal the ways in which the category of "intelligence" with respect to animals has received a tremendous amount of critical attention within contemporary animal studies, and popular science (e.g. Philip Sopher, "What Animals Teach Us About Measuring Intelligence," The Atlantic, February 27, 2015, www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/02/what-animals-teach-us-about-measuring-intelligence/386330/.).

[3] John M. Marzluff, Jeff Walls, Heather N. Cornell, John C. Withey, and David P. Craig, "Lasting Recognition of Threatening People by Wild American Crows," Animal Behaviour 79 no. 3 (2010): 699-707, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347209005806.

[4] John M. Marzluff and Tony Angell, In the Company of Crows and Ravens (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005): 152–195.

[5] Thomas van Dooren, Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014): 125–144.

[6] Kaeli N. Swift and John M. Marzluff, "Wild American Crows Gather Around Their Dead to Learn about Danger," Animal Behaviour 109 (2015): 187–197, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347215003188.

[7] Jeff Blagdon, "How Emoji Conquered the World," The Verge, 4 March 2013, www.theverge.com/2013/3/4/3966140/how-emoji-conquered-the-world.

[8] Unicode Consortium, "Emoji Encoding Principles," www.unicode.org/emoji/principles.html (Accessed 5/11/2021).

[9] Ibid. According to the Emoji Encoding Principles, "The major vendors have indicated that they want to hold to an emoji 'budget' each year of about 70 new characters (and limits on emoji sequences as well). Each additional emoji can be a burden on memory, UI usability and development cost — the memory impact is especially important for mobile devices in emerging markets."

[10] Bethany Berard, "I second that emoji: The standards, structures, and social production of emoji," First Monday 23 no. 9 (September 2018): www.journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/fm/article/download/9381/7565. The current Unicode Emoji Proposal Submission guidelines are here: www.unicode.org/emoji/proposals.html#submission.

[11] A number of programs and applications allow individuals to generate their own emoji for use within and across specific platforms (e.g. Emojily for iPhone/iOS, Emoji Maker for Android). Those idiosyncratic symbols don’t have a specific numeric value within Unicode or ASCII. As a result, they most often appear as empty boxes outside the specific platforms for which they are created—indicators that something has been lost in translation and decoding.

[12] Jenny Stinehour, "Proposal for Emoji: CROW; RAVEN," 6 May 2019, www.unicode.org/L2/L2019/19307-crow-emoji.pdf.

[13] Unicode, "Unicode 14.0 Delayed for 6 Months," 8 April 2020, www.home.unicode.org/unicode-14-0-delayed-for-6-months/.

[14] Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (Medford, MA.: Polity Press, 2019), 11.

[15] Reid J. Epstein and Nick Corasaniti, "Inside Democrats' Scramble to Repel the G.O.P. Voting Push," The New York Times, 7 May 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/05/07/us/politics/democrats-republican-voting-rights.html (Accessed 5/12/2021).

[16] Marina Magloire, "Black Bereavement White Condolences," Boston Review, 19 June 2020, www.bostonreview.net/race/marina-magloire-black-bereavement-white-condolences?fbclid=IwAR2GmmAqTuLv-hw-B_O85cbTWg_hetGk9PNNAYgh_pVzk09czEKVBGEjQys.

[17] van Dooren, The Wake of Crows, 6–7.

[18] Christina Sharpe, "Still Here," TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies 40, (February 2020): www.utpjournals.press/doi/full/10.3138/topia.2019-0013; Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 21.

[19] Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020): 2.

[20] See Ryan Broderick, "Chinese WeChat Users Are Sharing A Censored Post About COVID-19 By Filling It With Emojis And Writing It In Other Languages," BuzzFeed News, March 11, 2020, www.buzzfeednews.com/article/ryanhatesthis/coronavirus-covid-chinese-wechat-censored-post-emojis.

[21] Luke Stark and Kate Crawford, "The Conservatism of Emoji: Work, Affect, and Communication," Social Media + Society (July-December 2015): 4.

[22] Arundhati Roy, "The Pandemic is a Portal," Financial Times, 3 April 2020, www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca (Accessed 7/12/2020).

[23] Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, 3–8.

[24] Ibid, 22.

[25] Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 28. For Wilson, the unequal distribution of the "vulnerability to premature death" is a central definition of racism. Gilmore's analysis is essential for all discussions of vulnerability, but has not been regularly cited. See Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti, Leticia Sabsay, "Introduction" in Vulnerability in Resistance, ed. Butler, Gambetti, Sabsay (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 5.

Paige Sarlin is a filmmaker, artist, and scholar. Her first film, The Last Slide Projector, premiered at the Rotterdam International Film Festival in 2007. Her writing has been published in October, Re-Thinking Marxism, Discourse, and Framework. She is currently finishing a book- length manuscript entitled "Interview Work: The Genealogy of a Documentary Form." She is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Media Study at the University of Buffalo/SUNY.