Becoming Opaque, Becoming No-Body: Imagining Trans Futurity Beyond Remembrance

Thursday, February 1, 2024 at 10:10PM

Thursday, February 1, 2024 at 10:10PM Kanika Lawton

[ PDF Version ]

20 November 2021 marked the 22nd Transgender Day of Remembrance (TDOR), an annual observance that, as described by the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD), an LGBTQ+ American media monitoring organization, “honours the memory of the transgender people whose lives were lost in acts of anti-transgender violence.”[1] 2021 was also the deadliest year on record for transgender and non-binary people in the United States.[2] According to the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), the largest LGBTQ+ advocacy group in the United States, at least forty-seven trans and non-binary people were killed; up from forty-four reported killings in 2020, the previous deadliest year on record since the FBI began tracking anti-transgender violence in 2013.[3] In response to this ongoing crisis, HRC published a thirty-five page report entitled “Dismantling a Culture of Violence: Understanding Violence Against Transgender and Non-Binary People and Ending the Crisis,” arguing that “it’s not enough to grieve the loss of victims of violence against transgender and non-binary people. We must honor their memories with action.”[4] Yet a fissure develops within their assertion that a lack of visibility perpetuates violence. The report insists that “we must increase the cultural visibility of transgender and non-binary people and ensure their full inclusion within all communities” through, among other strategies, raising awareness of transgender and non-binary identities and supporting “accurate” and “authentic” trans representation in mainstream media.[5] My discomfort with this assertion lies in the claim that safety can be inscribed into law within the very system that also allows bills to pass, whose goal is the legislating of transgender people out of existence. Visibility as a precondition to state-assumed (yet not guaranteed) safety effaces the violence inherent in the consequences of being made visible outside of own’s own will.

What happens, then, when increased awareness of transgender, non-binary, and otherwise gender non-conforming lives becomes caught up in the increased awareness of the ways in which such life is made unlivable, when making visible trans life means making hypervisible the supposed predisposition of its always-already ending? The virtuality of Trans Day of Remembrance commemorations, such as the uploading of images of now-dead trans people of color on “In Memoriam” webpages and the supposed perpetuity of the digital afterlife for trans people whose lives were materially cut short, foregrounds my concerns over what it means to imagine “queer and trans vitality” beyond the hypervisibility of trans death and its online circulation of remembrance.[6] Moving beyond remembrance and the memorialization practices that suture trans life to its extinguishment rather than its riotous possibilities, I consider this to be part of a future-oriented project built on a teleological untethering of our hostile, cisnormative present and its death-making logic—an untethering that asks us to imagine “another end of the world” so that we can begin the work of undoing that which was made to undo us.[7] This article proposes queer and trans methods of moving, living, and flourishing that disrupt the surveillant capture of trans life as always-already marked for death by refusing recognition and visibility, instead turning to opacity and its shifting modalities of relations as a way of being elsewhere. That is, the mutuality of opacity and trans livability, of turning oneself circumstantially nonvisible in order to visualize other forms of living, impinges such theorizing with praxis-informed strategies. This is not a singular attempt to answer what it means to work towards trans futurity, but a series of mutually constitutive gestures that places queer and trans solidarity as a durational process of affective connection at the forefront, where to know how to make ourselves and each other unknowable, unrecognizable, and unclockable through reciprocal potentiality is the first step towards unmaking the world into a place it cannot imagine, but which we can make real regardless.

Trans Day of Remembrance was founded by transgender advocate Gwendolyn Ann Smith in 1999, who organized a vigil in honor of Rita Hester, a trans woman who was murdered in 1998.[8] While the vigil was held in Hester’s name, it commemorated every trans person killed by anti-trans violence since her death, thus beginning the tradition of reading a list of names of those killed that year, read on every November 20. HRC’s own “In Memoriam” seems to scroll without end, filled with the photographs of now-dead trans people arranged in a grid on the webpage before opening into individual obituaries, which includes each person’s name, photograph, and the city where they were found dead.[9] While not every obituary mentions the method by which they were killed—the ones that do overwhelmingly point to gun violence—each of the forty-seven obituaries in the 2021 report uses the words “killed,” “fatally shot,” or both to lead the text, describing where, when, and how each trans person memorialized was violently taken from this world. What remains of their lives outside of their killings are often scant of details: some are remembered by friends on social media, while others are known only by the high school they graduated from. Still others are so unknown—at least online—that the obituary meant to commemorate their lives become an abject reminder of what little life was available to them before their violent deaths. The photographs themselves point to this unknowingness of the full richness of their lives outside of a self that has been exhumed; most of them are selfies, taken at different angles with varying degrees of camera quality. We do not know how these photos were obtained—were they shared on social media? Among friends? Found on their phones after death? —yet there is a disconcerting dimension to this framing of self-portraiture with obituary, with the knowledge that such visuality—such visibility—is the only image we have “In Memoriam” since they were taken by those who were not alive to write their own digital remembrance.

Imagining queer and trans futurity beyond an aesthetics of visibility and its violences leads, in turn, to a reimagining of the conditions of visibility itself. A practice of opacity, or a tactic of nonexistence that is neither invisibility nor disappearance, is a potential mode of escape from the violent surveillance of trans and racialized bodies that makes oneself irreducible to a system that refuses to recognize trans lives as worthy of life itself. Rather than strip oneself of difference, becoming irreducible allows one to remain unknowable, yet not un-alive; a mode of non-living in the eyes of a system that already marks trans bodies for death by generating forms of living elsewhere. Yet who is privy to this form of opacity?

Restructuring opacity away from white mediation toward dark sousveillance and its methods of “looking back” ushers the full potential of opacity’s life-giving capacities. Grounded in linguistic roots (sous as looking up, or looking back at those who look down at you, who surveil), Simone Browne describes dark sousveillance as “imaginaries that are oppositional and that are hopeful for another way of being.”[10] This oppositional stand, this rendering of oneself out of sight, makes itself explicitly known through the deployment of “Black looks,” a reality-bending act of staring back, of refusal in the face of those who refuse to consider the Black body as worthy of life. Black looks situates Blackness both into the disruptive stare of the individual against surveillant and state violence while making irreducible the ways in which Black gender marks itself across the body through “both the parameters of impossibility but also its methodologies of rebellion.”[11]

Seen by the state yet unknowable, Black looks is a method of disrupting white-mediated modes of remembering Black trans death at the expense of Black trans life, of letting the dead “look and talk back,” and of making the common refrain “give Black trans women their flowers before they’re gone” not merely speech, but a rallying cry to action that is not only a declaration of world-shattering possibility but the very conditions under which it can break open.

Browne continues, writing that such a stare “is the type of ‘eyeballing disposition’ that disrupts racializing surveillance where, as Maurice O. Wallace discusses, such looks challenge the ‘fetishizing machinations of the racial gaze.’”[12] The very “fetishizing machinations” that Black looks disrupt are reproduced during TDOR memorials, where the names of the disproportionate number of Black and Latinx trans women killed are often read out to predominately white audiences. C. Riley Snorton and Jin Haritaworn note this racialized discrepancy between those who are remembered and those who remember when they ask how the deaths “of trans women of color circulate, and what are the corporeal excesses that constitute their afterlives as raw material for the generation of respectable trans subjects?”[13] Rather than clamor for respectability from the very systems that mark us for structural failure, Black looks are not only a way to disrupt such memorializing practices, but a survival tactic.

Such looks open up what opacity can do and who it protects. In an interview with Browne, Zach Blas contends that opacity is “an anti-biometric concept that is particularly sensitive to minoritarian lives.”[14] Yet we see the failure of opacity—or at least its constricted formulation—in memorializing practices that make the names, photos, and deaths of trans people—especially trans people of color—legible, downloadable, and shareable across digital space, but not who they were, who they loved, and what they hoped and dreamed for. While dark sousveillance and Black looks open up where opacity can go, I am curious about where it can escape, and how such escape can be a generative process of making trans life livable outside of detection, recognition, and remembering in death.

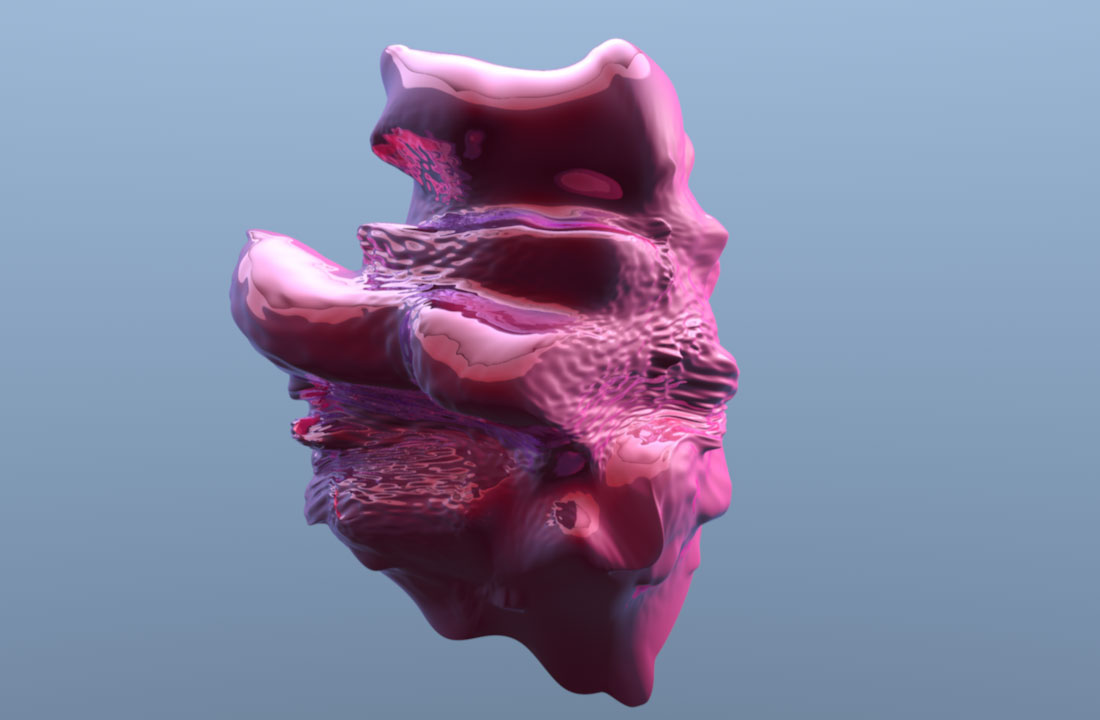

Escaping by obfuscating the very conditions of one’s representation runs through Blas’s Facial Weaponization Suite (2012-14) and its companion short film, Facial Weaponization Communiqué: Fag Face (2012), both of which are available to view for free on Blas’s website. Modeled after the aggregated facial data of workshop participants, these amorphous, collective masks cannot be detected as human by facial recognition technologies. I focus on Fag Face, a fluorescent pink, bulbous face mask Blas wears, his voice digitally anonymized alongside his anonymized face. Fag Face was built using the biometric facial data of queer men’s faces in response “to scientific studies that link determining sexual orientation through rapid facial recognition techniques.”[15] Pushing against the scientific claim of being able to clock someone as queer or trans (and the violence this entails), Blas and an anonymized feminine voice (who speaks as the pink bulbous mass in the process of becoming Fag Face) refute governmental use of biometric technologies as modes of surveillance and control over populations, offering “facelessness” as a “politics of escape, forms of living elsewhere.”[16] Fag Face makes itself unknowable through the collection of excess knowledge into a mass of plastic incomprehension. Weaponizing the face through such digitally fabricated, yet wearable masks create “a faceless threat, the queer opaque” that is visible yet undetectable, in the open yet incomprehensible; a method of refusing surveillance by becoming impossible to surveil.[17]

Figure 1: Facial Weaponization Communiqué: Fag Face

Fag Face as an example of a collective mode of escape demonstrates, through speculative design created with trans people at the front of its prototypical and theoretical work, that “facelessness, escape, and becoming imperceptible are serious threats to the state.”[18] The film ends on a note of a future elsewhere; a not-yet-known but graspable place that hints at an ungovernmentality built on possibility: “Becoming non-existence turns your face into a fog, and fog makes revolt possible.”[19]

Becoming non-existence is tied up in what it means to be “no-body.” Writing on the problem of recognition for trans life, Eric A. Stanley asks: “how can we be seen without being known and how can we be known without being hunted?”[20] The “double bind of recognition”[21] names how “being seen by the other brings you into the world—into the field of visibility. But for those already on the edges of vitality . . . it is often that which also takes you out of it.”[22] Becoming a “no-body against the state” is a potential way out. A “‘no-body against the state’ . . . stands against the sovereign promise of positive representation and the fantasy of sovereignty as assumed under claims of privacy. Read not as absolute abjection but as a tactic of interdiction and direct action, being no-body might force the visual order of things to the point of collapse.”[23] Since there is no way for the state to comprehend, let alone surveil, such bodies and the lives they live, being no-body forces an opaque existence not through concealment from the state, but the collapse of its very system of surveillance and its “technology of anticipation”[24] by ensuring that it cannot anticipate us. No-bodiness is a future-oriented mode of flourishing for trans and racialized lives that expands what queer opacity encompasses, what it looks like, and what ends it can bring about. Offering a possible answer to Blas’s question “how do we flee this visibility into the fog of a queerness that refuses to be recognized?,”[25] Stanley tells us “opacity offers us a glimpse, however fleeting, of the sensuous beauty in the ruins of representation’s hold” and that “abolition’s generativity also insists we must summon images where no-bodies can gather, not to become somebodies before the state but to envision, together, the possibility of another end of the world.”[26]

The end of the world that worked to end us leads me to micha cárdenas’ proposal of a “trans of color poetics as a poetics of media and movement that works to increase the chances of life for trans people of color and reduce the likelihood of death.”[27] I owe much of my interventions to her articulation of the stitch: the connection of two separate entities into one as “a poetics of object making as well as a process of making new concepts.”[28] Such poetics involves the cut, which means “the stitch brings the affect of pain into this consideration of creation and facilitates a change in shape, a shift”[29] that is also constitutive of the freedom of opacity and its refusal to make knowable trans livability for cis intervention. I see this cutting, shaping, and shifting in the emergence of Trans Day of Resilience—which occurs each year on November 19, the day before TDOR—and how it visualizes trans futurity through the sharing of trans artworks and poetry.

Founded alongside the Audre Lorde Project in 2014 and lead by Forward Together, Trans Day of Resilience is “an annual love offering to trans people of color everywhere.” Centering trans people of color—who, as Jin Haritaworn, Adi Kuntsman, and Silvia Posocco have argued, “it is in the moment of their death that those most in need of survival become valuable”[30] during TDOR vigils—Trans Day of Resilience resists both the death-making conditions of life under cisnormative constraint and their death-repetitive practices, turning toward the artworks and voices of those who are alive since “our rebellious mourning recommits us to the living.”[31] With art as a method of resilience, the Trans Day of Resilience website ends with a mutual call for joy, care, and futurity: “May this project, for and by trans people of color, help us see ourselves safe and cherished, rested and healed, fully alive. Let’s dream and shape an irresistible future together.”[32] This other iteration of TDOR is a stitch that allows for a different kind of visibility outside of the white-mediated gaze, or opacity as “a form of solidarity without being grasped.”[33] It is, perhaps, a way to transform Trans Day of Remembrance from a place of mourning to action: “mourn for the dead, but fight like hell for the living,” or a trans of color poetics that becomes “not just poetics of survival, but poetics that stretch toward liberation” and its unseen horizons.[34]

Through these short forays into theoretical and practical terrains, I have gestured towards mutually constitutive openings that imagine queer and trans futurity beyond remembrance that, I argue, are integral for a queer and trans refusal of the world as we know it, and its capture of those gone and yet to be taken. For the communities I belong to, in which solidarity is a process of continued care, and to the scholars and artists whose work inform my own ways of thinking and imagining, honoring those now gone means dismantling the very conditions that lead only to trans death and not trans life, only to remembrance and not futurity, only to memorialization and not livability. There are forms of being elsewhere, ways to flourish together, a “queer and trans vitality” that cannot be detected or known or flattened by the death world we are currently in. It is here that “getting ungovernable is both a trace of, and a map for, ‘becoming liberated as we speak,’” continuing on toward the end of that which will not end us with it.[35]

Notes

[1] “Trans Day of Remembrance,” GLAAD, www.glaad.org/tdor (accessed 6 December 2021).

[2] At the time of this writing, 2021 was the deadliest year ever for transgender and gender non-conforming people, surpassing 2022, which recorded at least thirty-eight violent deaths. For more on this report, see “Fatal Violence Against the Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Community in 2022,” HRC, www.hrc.org/resources/fatal-violence-against-the-transgender-and-gender-non-conforming-community-in-2022 (accessed 10 December 2022).

[3] “An Epidemic of Violence 2021: Fatal Violence Against Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming People in the United States in 2021,” HRC, reports.hrc.org/an-epidemic-of-violence-fatal-violence-against-transgender-and-gender-non-confirming-people-in-the-united-states-in-2021?ga=2.58528682.1678236676.1639161771-962654078.1639161771 (accessed 6 December 2021).

[4] “Dismantling a Culture of Violence: Understanding Violence Against Transgender and Non-Binary People and Ending the Crisis,” HRC, reports.hrc.org/dismantling-a-culture-of-violence?ga=2.105836928.2030111018.1654230638-344527879.1654230638 (accessed 2 June 2022).

[5] “Dismantling a Culture of Violence.”

[6] Jin Haritaworn, Adi Kuntsman, and Silvia Posocco, “Introduction” in Queer Necropolitics, eds. Jin Haritaworn, Adi Kuntsman, and Silvia Posocco (London: Routledge, 2014), 18.

[7] Eric A. Stanley, Atmospheres of Violence: Structuring Antagonism and the Trans/Queer Ungovernable (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021), 90-91.

[8] “Trans Day of Remembrance.”

[9] “An Epidemic of Violence.”

[10] Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 21.

[11] Stanley, Atmospheres of Violence, 83.

[12] Browne, Dark Matters , 58.

[13] C. Riley Snorton and Jin Haritaworn, “Trans Necropolitics: A Transnational Reflection on Violence, Death, and the Trans of Color Afterlife,” in The Transgender Studies Reader 2, eds. Susan Stryker and Aren Z. Aizura (London: Routledge, 2013), 74.

[14] Simone Browne and Zach Blas, “Beyond the Internet and All Control Diagrams,” New Inquiry, 24 January 2017, thenewinquiry.com/beyond-the-internet-and-all-control-diagrams/ (accessed 6 December 2021).

[15] Zach Blas, “Facial Weaponization Suite (2012–14),” zachblas.info/works/facial-weaponization-suite/ (accessed 6 December 2021). Facial Weaponization Suite is available to view on Blas’s website as a photography series.

[16] Zach Blas, Facial Weaponization Communiqué: Fag Face(2012), zachblas.info/works/facial-weaponization-suite/ (accessed 6 December 2021). Facial Weaponization Communiqué: Fag Face is available to view for free on Blas’s website.

[17] Facial Weaponization Communiqué: Fag Face.

[18] Facial Weaponization Communiqué: Fag Face.

[19] Facial Weaponization Communiqué: Fag Face.

[20] Stanley, Atmospheres of Violence, 87.

[21] Stanley, Atmospheres of Violence, 86.

[22] Stanley, Atmospheres of Violence, 86.

[23] Stanley, Atmospheres of Violence, 87.

[24] Stanley, Atmospheres of Violence, 78.

[25] Facial Weaponization Communiqué: Fag Face.

[26] Stanley, Atmospheres of Violence, 91.

[27] micha cárdenas. “Trans of Color Poetics: Stitching Bodies, Concepts, and Algorithms,” S&F Online 13–14, no. 3–1 (2016): sfonline.barnard.edu/traversing-technologies/micha-cardenas-trans-of- color-poetics-stitching-bodies-concepts-and-algorithms/.

[28] cárdenas, “Trans of Color Poetics.”

[29] cárdenas, “Trans of Color Poetics.”

[30] Haritaworn, Kuntsman, and Posocco, “Introduction,” 17.

[31] “Trans Day of Resilience,” Forward Together, tdor.co/ (accessed 6 December 2021).

[32] “Trans Day of Resilience.”

[33] Stanley, Atmospheres of Violence, 88.

[34] cárdenas, “Trans of Color Poetics,” 45.

[35] Stanley, Atmospheres of Violence, 123.

Kanika Lawton is a PhD student at the University of Toronto's Cinema Studies Institute and the Mark S. Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies, as well as a 2023-2024 Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Sawyer Seminar Graduate Fellow with the Evasion Lab at the Centre for Diaspora and Transnational Studies. Their SSHRC-funded research foregrounds an aesthetic and political critique of surveillance, arguing that it both preludes and produces scenes of violence within and beyond the frame. Their work has been published in Spectator.