Staging Revolution: The OWS Encampment at Zuccotti Park

Sunday, October 25, 2015 at 5:58PM

Sunday, October 25, 2015 at 5:58PM Alison Vogelaar

[ PDF Version ]

On September 17, 2011, the hustle and bustle of New York City’s financial district was interrupted by a protest-turned-encampment that ended in Zuccotti Park. Little did onlookers and participants know that just a month later that “local” interruption would become a “global” movement credited with challenging the dominant discourses of global neo-liberalism. This was made possible in part by the rhetorical and material force of “the encampment,” which functioned not just as a symbol of the movement but, more importantly, as a stage upon which the construction and performance of alternative discourses was made possible. More specifically, the encampment used place to “stage” (and make visible and material) the problem of the corporate colonization of the public sphere and its solution—the re-appropriation of public spaces, discourses, and subjectivities.

Place has become simultaneously hyper- and irrelevant in global postmodernity and the notion of placelessness has been experienced as both a blessing and a curse. In many parts of the world, humans have been “freed” from place and now create, consume, forge and maintain identities, relationships, and work, “out of place.” Nevertheless, so much of what ails us (environmentally, politically, emotionally and physically) is a partial product of our disregard for the places in which we reside and on which we depend. The latter part of the 1980s saw the re-assertion of the significance of space/place in critical and social theory.[1] Resistance groups, movements and identities figured prominently in this line of research in so much as they draw attention to the power of place and in so doing “question the naturalness and absoluteness of assumed geographies.”[2]

Imbued with meaning and consequences, place is an inherently rhetorical phenomenon that is particularly relevant to the study of protests.[3] Protests are embodied and spatial phenomena that rely heavily on “the confluence of physical structures, locations and bodies” for material and symbolic effect.[4] Studying social movement protests from the lens of place “recognizes not only that social protest is inherently out of place, but also that place is more than just a backdrop for the rhetoric of social protest.”[5] Place functions in many cases as the very text of social movements, out of which many movements make claims and perform grievances and/or desires. What is more, places are malleable and ephemeral phenomena that “are constantly being reiterated, reinforced, or reinterpreted”[6] through rhetorical practices and which “themselves contest and remake social structures.”[7] Protest groups alternatively use place to reiterate, disrupt or resist dominant meanings associated with protest sites.

The occupation of public and private spaces has been a standard tactic of many resistance groups including but not limited to farmers’ and workers’ movements in Latin America, Asia and Southern Europe as well as civil rights, student, pro-democracy, peace and environmental groups in the United States and Great Britain, and most recently the pro-democracy movements in the Arab world. This is not surprising given that many movements and opposition groups are fueled by the perceived absence, disappearance, or manipulation of public “spaces” of shared governance and cultural production and the uneven spatial development and colonization associated with neo-liberal regimes.[8] Protest encampments are distinct forms of protest-in-place as they deliberately and strategically re-appropriate and manipulate public and private places according to the symbolic and functional needs of protest groups.

OWS: Born an Encampment

“On September 17, we want to see 20,000 people flood into lower Manhattan, set up tents, kitchens, peaceful barricades and occupy Wall Street for a few months.”[9] This pithy call, issued by the Adbusters magazine, sparked what has come to be known as Occupy Wall Street, a movement that many assert has shifted the paradigm of nonviolent protest. OWS was defined by its use of new and old social movement tactics, but was most visible through its encampment in Lower Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park, which quickly spawned a series of urban and suburban encampments in cities across the globe. The encampment itself became a sort of media spectacle as the dramatic saga between protesters, the site’s owner (Brookfield Office Properties), the NYC mayor (Michael Bloomberg) and the police played out on mainstream media channels and ended in its predictable evacuation.

Though it has been closed to habitation since November 15, 2011, the Occupy Wall Street encampment has become a “symbolic token”[10] of the now global movement. Though the symbolism of the encampment at Wall Street lives on in memories, texts, and images, there is no doubting that the encampment’s closure profoundly altered the movement’s rhetorical force. Understanding this, OWS organizers quickly turned to alternative spaces and places (e.g. cyberspace and Occupy Your Block) where the movement lives on, albeit in an altered form. In spite of its eventual destruction, the encampment at Wall Street was a doubly powerful rhetorical maneuver that functioned both symbolically and pragmatically to draw attention to and challenge contemporary spatial politics and place-relations.

Figure 1. Staging Disparity. Day 60 - November 15, 2011. Photo by David Shankbone. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Staging Disparity: The Tragedy of the Commons

The very public evacuation of the encampment at Zuccotti Park was the defining moment of the OWS movement. Indeed, a movement leader could not have orchestrated a more symbolically profound image event. The OWS “eviction theater,” broadcast on the front pages and stages of the mass media, revealed the movement’s main grievance: America is owned by a ruling few and the engines of civil society (police, local government, mass media) are in their service. Indeed, everyone played their parts brilliantly: using a sanitation clause, the park’s owners, Brookfield Office Properties Inc. (owned by the Canadian Brookfield Asset Management Inc.) had the private park evacuated by public servants (the police, mayor, state judiciary). The private mainstream media channels interpreted and recorded the evacuation drama in predictable and simplistic frames, pitting public against public—barbaric and sometimes brave police against fanatic and sometimes helpless protesters. And after much contestation about what could and should be permitted on the seemingly oxymoronic “privately owned public space,” the private trumped the public.

The final battle cry of the encampment organizers, “you can’t evict an idea whose time has come” was powerful but it missed its critical follow up statement—“you can evict people from a privately owned public space.” And therein lies the problem of contemporary neoliberal societies—public resources (spaces, ecosystems and their components, cultural artifacts) are increasingly owned by powerful private entities and rented or sold back to “the public” with limitations, disclaimers, strings attached. As a “privately owned public space,” Zuccotti Park was more than a geographically convenient place to make the invisible, visible, it was itself a manifestation of the problem of neoliberal colonization. In this way, it became the perfect platform on which to bring the rapidly proliferating neoliberal colonization of public resources and spaces from the backstage into the frontstage. And the OWS encampment’s eventual, predictable and, even, desirable evacuation was critical to the transmission of this message.

According to sociologist, Thomas Geiryn, “places have power sui generis, all apart from powerful people or organizations who occupy them: the capacity to dominate and control people or things comes through the geographic location, built-form, and symbolic meanings of a place.”[11] Zuccotti Park is one such site, rich in history, geography, architecture and symbolism and deeply enmeshed in the longstanding tension between public and private interests in the United States. It is, on the one hand, a privately-owned plaza located in downtown Manhattan’s financial district just blocks from Wall Street between the busy Broadway, Trinity Place, Liberty and Cedar Streets and has, on the other hand, been the “public” stage for many important civic events in American history—the site of the first coffee house (as “civic forum”) in New York City (and some assert in the nation), the “staging” ground for the 9/11 World Trade Center clean-up, and the physical “headquarters” of the global social movement, Operation Occupy Wall Street. It is fertile ground.

As a “privately owned public space,” the park is a complex space, part and parcel of the contemporary problems of the shrinking of the commons, the drying up of public funds, and the complex intermingling between government and corporations at the heart of these transformations. According to placematters.org, the plaza is a product of a mid-twentieth century zoning policy that sought to restrict new development by encouraging the creation of open spaces, like plazas, in exchange for the building of high rises (“you can build a high rise that exceeds the code height if you make a plaza”). In this way, private organizations were given perks for providing parks once provided by public funds. According to Nancy Scola, corporations, builders and real-estate interests continue to “play the role forfeited by cash-strapped and deadlocked government” in New York City, citing Manhattan's Highline Park and Battery Park City, and Brooklyn's Brooklyn Bridge Park as the most recent examples.[12]

Up until the 2011 occupation, no one much thought or cared about the rules of conduct unique to a “privately owned pubic park” like Zuccotti. Indeed, the occupation has revealed the degree to which “the construction of these spaces seems to have outpaced our understanding of the relationship of the public to private-public spaces.”[13] For example, what rights to free speech and assembly does one have in a private-public park? And whose job is it to police such spaces? While the park’s special status was advantageous to OWS protesters because—unlike city parks which all have curfews and do not permit camping—many parks and plazas developed under the original zoning rules are open around the clock,[14] its eventual evacuation revealed the obvious oxymoron at the heart of this pseudo-public space.

Prior to occupation, the concrete plaza, sandwiched on all sides by high rises that house private corporations and dotted with planters, trees, sculptures, and benches served as little more than a corridor for local workers on their way to office spaces, and a rest-stop for white-collar workers during their lunch breaks and tourists visiting the district.[15] As “made places,” urban sites are more than mere geographical sites and function accordingly as both metaphoric and literal structures of power relations. In many urban sites, like Manhattan’s financial district, it is easy to “observe hierarchies where some figure more prominently than others.”[16] Indeed, the location and landscape design of Zuccotti Park is heavily infused with conceptions of proper conduct and belonging implying some social categories, subjectivities and activities and disregarding others.[17] These unspoken (but highly symbolic) architectures and codes indicate who is legitimately entitled to occupy, possess and “act-out” in different spaces and who is not.[18] Indeed, initial reactions to the encampment, highlighted the out-of-placeness of (some of) the movement’s subjectivities (“hippies” and “unemployed”) and activities (“camping,” “drum circles”).

That said, the juxtaposition of the public (horizontal) and private (vertical) spaces occupied by “the 99%” and “the 1%” at this site provided a powerful symbol (and evidence) of the movement’s main claim and grievance: the division between the 1% and the 99% is profound and unjust. Whereas the orderly corporations and employees (leaders and food soldiers of the 1%) were hidden and protected in tall, cement and steel structures, the disorderly occupiers (the 99%) were visible and unprotected, protesting at the ground level, in the open air secured only by thin nylon tents when weather worsened or night fell. Indeed, this juxtaposition was a rhetorically powerful manifestation of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon where park occupiers (the 99%) were totally visible and vulnerable and the financial and political elite (the 1%) were invisible, protected and, in many cases, able to observe the activities of the encampment below. As in the “Bonus Army” encampment set up in Washington DC in 1932 to petition for government-assisted veteran relief from the Depression, “the city's celebration of material wealth [was] foiled by unavoidable reminders of society's negligence” made manifest by the encampment.[19] Whereas the disorderly Bonus Army camps of the 1930s were “a blunt reminder of the [Hoover] administration’s failures,” the OWS encampment served as a visualization of the failures of the current financial system and the political forces behind it.[20]

Like Washington DC, New York City’s Manhattan District is a provocative symbol of the wealth and success of the nation. Encampments such as OWS build on and subvert that meaning by drawing (often visual) attention to the problems of such power and its manifold abuses and failures. Indeed, much of the rhetorical impact of OWS can be attributed to the convergence of physical structures, locations and bodies, as they came together to tell an eclectic but provocative “David and Goliath” story about the haves and the have-nots created and maintained by the current political-economic regime and, most importantly, about the corporate colonization of public spaces and resources that complicate the telling of this story.

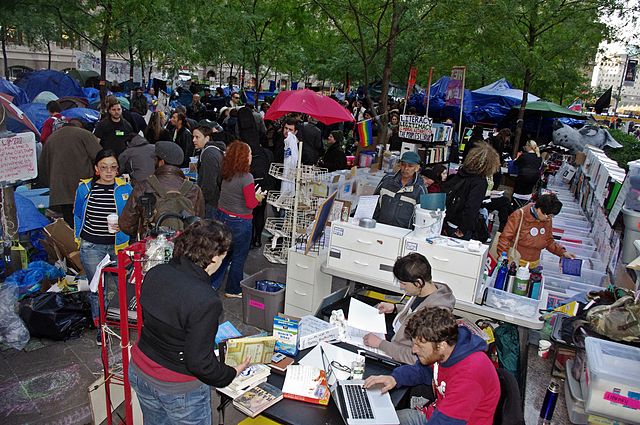

Figure 2. Staging Democracy. Day 47 Occupy Wall Street - November 2, 2011. Photo by David Shankbone. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Staging Revolution: “This is What Democracy Looks Like”

In addition to performing the “tragedy of the commons,” OWS protesters performed a concurrent “theater of the oppressed”[21] whereby performance and place-making were used to explore power relations, imagine alternatives and promote change by embodying the practices and subjectivities of democratic citizenship and grassroots community. During the occupation, the corporate plaza was transformed into a campsite-cum-town square-cum-theater populated with colorful (at times grungy) tents, signs, people and performances and much effort was put into the manipulation of the place both materially and symbolically.

One of the first and most important demonstrations of the “the play of agency and contingency in place-making”[22] was the almost immediate attention to place-naming. As in the 1969 American Indian Movement’s occupation and re-naming of Alcatraz Island and its buildings,[23] the OWS encampment participants used naming to contest old, and create new, meanings. “Zuccotti Park” thus became “Liberty Plaza,” the “plaza” became an “encampment,” the “protest” became an “occupation,” lunch benches and walkways became “media centers,” “kitchens,” and “libraries.” And in the process, the orderly plaza became a messy town center, overflowing with people, activities, and meaning.

The notion that “engagement and estrangement can be built-in” was not lost on OWS. The encampment’s design was a clear embodiment of the movement’s ideologies of anarchism in relation to horizontalism.[24] Internal and external communication about the architecture of the site indicate that its designers were well aware of the seemingly contradictory design theories which assert on the one hand that well-designed public spaces draw people to them, and on the other that the places most conducive to community are not designed at all.[25] The design also highlighted the conflicting ways in which the formal qualities of a built environment exert a powerful effect on individuals by shaping the possibilities for behavior, all while individuals shape and infuse their spaces with meaning.[26] In addition to providing a symbolic and material space in which people could enact grassroots community, the OWS encampment also provided the fundamental resources lacking in the current system (community, access to information and communication channels, nourishment, healthcare, housing). And indeed, unlike many other protests, which often focus on the symbolic over the practical, much of what was performed at the Liberty Plaza encampment was just that, a performance of the business of democratic daily life (eating, sleeping, communing, organizing, etc.) in public view.[27]

The Occupy Wall Street encampment was more than a protest; it was a demonstration of the problems and possibilities of space and place in this dynamic moment in time. Using the historically, geographically, symbolically and structurally powerful site at Zuccotti Park, OWS participants “staged” the problem of the corporate colonization of the public sphere and its solution—the re-appropriation of public spaces, discourses, and subjectivities. The first “stage” manipulated the distinct (structural, legal, symbolic) features of Zuccotti Park to demonstrate the profound disparities between the ‘haves’ (the private) and ‘have nots’ (the public) in the current paradigm. The second “stage” transformed the grey plaza into a colorful “commons” wherein movement participants embodied and demonstrated democratic self-governance. And in spite of (or indeed because of) its eventual evacuation, the encampment (the stage) and its performances and subjectivities made evident the sense in which "being human—human be-ing-ness—means to be creative in the sense of remaking the world for ourselves as we make and find our place and identity."[28]

Endnotes

[1]Tim Cresswell, In Place/Out of Place: Geography, Ideology, and Transgression (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996); and Edward W. Soja, Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory (London: Verso Books, 1989).

[2]Cresswell, In Place/Out of Place, 149.

[3]Danielle Endres and Samantha Senda-Cook, “Location Matters: The Rhetoric of Place in Protest,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 97, no. 3 (2011): 258.

[4]Endres and Senda-Cook, “Location Matters,” 260.

[5]Endres and Senda-Cook, “Location Matters,” 260.

[6]Endres and Senda-Cook, “Location Matters,” 262.

[7]Endres and Senda-Cook, “Location Matters,” 260.

[8]Soja, Postmodern Geographies.

[9]Adbusters, "#OCCUPYWALLSTREET," Adbusters, July 13, 2011, http://www.adbusters.org/blogs/adbusters-blog/occupywallstreet.html.

[10]Bryan C. Taylor, “‘Our Bruised Arms Hung Up As Monuments’: Nuclear Iconography in Post-cold War Culture,” Critical Studies in Media Communication 20, no. 1 (2003): 1-34.

[11]Thomas F. Gieryn, “A Space for Place in Sociology,” Annual Review of Sociology 26, (2000): 474.

[12]Nancy Scola, “For the Anti-corporate Occupy Wall Street Demonstrators, the Semi-corporate Status of Zuccotti Park May Be a Boon,” POLITICO New York, October 2, 2011, http://www.capitalnewyork.com/article/politics/2011/10/3583314/anti-corporate-occupy-wall-street-demonstrators-semi-corporate-stat.

[13]Scola, “For the Anti-corporate Occupy Wall Street Demonstrators.”

[14]Lisa W. Foderaro, “Privately Owned Park, Open to Pubic, May Make its Own Rules,” The New York Times, October 13, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/14/nyregion/zuccotti-park-is-privately-owned-but-open-to-the-public.html?_r=0.

[15]The park was updated following the attacks of September 11 by the park’s owners who invested 8 million in renovations. Prior to this, the park was a very shabby concrete park used only as a path into the financial district. See Scola, “For the Anti-corporate Occupy Wall Street Demonstrators.”

[16]Julia Friday, “Prague 1968: Spatiality and the Tactics of Resistance,” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 53, no. 2, (2011): 160.

[17]Gieryn, “A Space for Place,” 465.

[18]Rionach Caseya, Rosalind Goudiea & Kesia Reeve, “Homeless Women in Public Spaces: Strategies of Resistance,” Housing Studies, 23, no. 6 (2008): 899-916.

[19]Lance Hosey, “Slumming in Utopia: Protest Construction and the Iconography of Urban America,” Journal of Architectural Education 53, no. 3 (2000): 154.

[20]Hosey, “Slumming in Utopia,” 146.

[21]Augusto Boal, Theater of the Oppressed (Pluto Press, 2000).

[22]Gieryn, “Space for Place,” 469.

[23]Endres and Senda-Cook, “Location Matters.”

[24]Gieryn, “Space for Place,” 477.

[25]Gieryn, “Space for Place.”

[26]Endres and Senda-Cook, “Location Matters”; and Gieryn, “Space for Place.”

[27]Ann Folino White, “Starving Where People Can See: The 1939 Bootheel Sharecroppers' Demonstration,” TDR/The Drama Review 55, no. 4 (2011): p. 14-32.

[28]Luca M. Visconti, John F. Sherry, Stefania Borghini & Laurel Anderson, “Street Art, Sweet Art? Reclaiming the ‘Public’ in Public Place,” Journal of Consumer Research, 37, (2010): p. 511-529.

Alison Vogelaar is an Assistant Professor of Communication and Media Studies and Co-director of the Center for Sustainability Initiatives (CSIF) at Franklin University Switzerland. Vogelaar received a Ph.D. in Communication from the University of Colorado at Boulder where she also completed a certification program in the Center for Science and Technology Policy Research. Her research interests include rhetorical theory and criticism with an emphasis in social movements, media activism, environmentalism, and space and place as well as the intersections of culture, sustainability and educational travel.