He’s Building a Model: Steven Spielberg, J.J. Abrams, Scale, and Super 8

By J.D. Connor

[ PDF version ]

Late in Act II of Jaws (dir. Steven Spielberg, Universal, 1975), with the Orca in hot pursuit of the great white shark, Hooper (Richard Dreyfus) tells Chief Brody (Roy Scheider) to walk out onto the pulpit. He’s taking a picture of the shark and needs “to have something in the foreground to give it some scale.”

Figure 1. Giving It Scale, Jaws

Brody naturally refuses Hooper, “Foreground my ass,” but obliges Spielberg.

Figure 2. Foreground, Jaws

The exchange asserts yet again the film’s insistence on the interplay between surface and depth, a play that has defined it from the opening attack on Chrissie through the Vertigo zoom in the attack on Alex Kintner. Here, Hooper and Brody remind us of the shark’s first dramatic appearance near the boat (Figure 3) while they set the stage for an analysis of Quint’s subsequent actions (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Chum Some of This, Jaws

Figure 4. Quin's Actions, Jaws

Flash forward four years, or 36, to 1979 or last summer. Just before the gargantuan train crash that launches us into Act II of Super 8 (dir. J.J. Abrams, Paramount/Amblin/Bad Robot, 2011), onscreen director Charles Kasnyk realizes that he may finally have what he has been looking for: “Production Value!” he screams.

Figure 5. Production Value, Super 8

In the ensuing chaos, the camera will be knocked over, and while lying on its side, clicking away, it will expose what is left of its magazine.

Figure 6. Automatism, Super 8

This automatic recording is the film’s central image, and it gave rise to the canted poster and the marketing campaign as a whole.

Figure 7. Poster, Super 8

As defined in Super 8, production value is not exactly the same thing as scale, but they exist in close conceptual proximity to one another. Both are things that happen in front of film cameras and that onscreen directors make explicit, which is to say that scale and production value are the sorts of concepts that seemingly require immediate stipulation so that they can serve as internal guides for our viewing. For Spielberg and Abrams, both scale and production value are functions of foreground/background relationships that hinge on a comparison to a body. With scale, we are plunging into a geometric relationship. It is a formal property of the image. But with production value, the relationship between the body in the foreground and whatever is going on in the background has become nearly numerical, a matter of population or expense. It is not a formal property of the image but a social property of its content. Abrams–style “production value” is what happens to scale when a certain kind of filmmaking attempts to retain its coherence under digital pressure.

Moving along the axis that connects Spielberg (who produced Super 8) to Abrams (who wrote and directed it) allows us to reckon with a group of questions that surround the digital turn. Part of the reason to trace this particular history is that Abrams and Spielberg both consider Abrams’s work to be an extension and elaboration of the project Spielberg began. A second reason, though, lies in the quality of the work itself—not simply that it is itself popular and formally rigorous, but that Spielberg and Abrams’s ability to theorize about the place of their work within the system, indeed, the ability of their production designers, cinematographers, editors, sound editors, effects editors etc., to do the same, makes their films not simply landmarks but nodes around which knowledge clusters in search of further elaboration.

As a first example, let us begin with Jurassic Park (dir. Spielberg, Universal, 1993), a crucial film in the history of digital production. As is usually the case in a Spielberg film, the distinction between what we might call the production narrative and the exhibition narrative collapses. The behind-the-scenes becomes “the scenes” with beneficial effects. In this case the making of Jurassic Park reset the balance of labor in the world of special effects, nearly wiping out model animators in favor of CGI teams at Industrial Light and Magic. Phil Tippett, who had dramatically advanced stop-motion animation technique, was stunned when he saw the first CGI of a hunting T-Rex. The motion was so lifelike, and the scale so believable, he recognized at once that the number of model shots would be slashed. “The change was devastating. I had different concessions…and all of a sudden, the plug was pulled.” Or, as he put it to Spielberg, “I think I’m extinct.” In the film, as Spielberg notes, that was the situation of the paleontologists. “Looks like we’re out of a job,” Dr. Grant says. Malcolm responds, puckishly, “Don’t you mean extinct?” “I kind of rubbed it in by using it in the film itself,” Spielberg grinned.[1] But it remained (on the surface) a joke between friends because Tippett’s animation crew found their way into the CGI process. They still manipulated articulated forms, but they reconceived their product. Instead of producing camera-ready poses, they generated data-points that the CGI animators would then flesh out and render.

Figure 8. CGI Data Points, Jurassic Park

Again, scale proves crucial. Spielberg initially wanted to rely on full-scale models for all the dinosaurs. Later, he opted for a hybrid approach: full-scale models for shots in which the dinosaurs interacted with humans, Tippett’s go-motion for wide shots, and CGI to blend them. Still later, he eliminated the go-motion, leaving only full-scale models and virtual dinosaurs. And for the final sequence, shot at the end of production when the full power of the CGI effects could be seen, he decided to use CGI dinosaurs even though they would be interacting closely with human characters. Jurassic Park thus contains within itself the history of the move from traditional to digital effects, even as it was responsible for that history. If Malcolm’s distorted reflection in the rain-filled footprint was the film’s emblem for onscreen suspense (Figure 8) its other emblematic reflection captured the offscreen story from Tippett’s point of view (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Emblem of Suspense, Jurassic Park

Figure 10. Tippett's Point of View, Jurassic Park

In The Virtual Life of Film, David Rodowick distinguishes between animation, in which individual frames are photographed in succession in order to give the illusion of movement, and “computer-generated movement,” a difference that comes to the fore with Jurassic Park. With the arrival of CGI dinosaurs, the “perceptual distinctiveness” between the “photographical” and the “autographical,” like the difference between Dick Van Dyke and the penguins in Mary Poppins, “is no longer present.” This is not, according to Rodowick, a change within photography, but a replacement of photographic transcription and succession by “digital synthesis” which in turn “produces an image and animates it from an abstraction—numerical manipulation.”[2] Here is how Phil Tippett put it:

“You are no longer constrained by materiality.” A sentence like that is precisely the sort of theorization that we should expect to occur when filmmakers are working on projects that are pre-tagged as landmark films, films that via demonstration effects and the concentration of aesthetic and industrial authority have the power to utterly upend longstanding labor and technological formations.

A decade later, in War of the Worlds, the sideview mirror’s function has been extended.

Figure 11. Sideview Mirror, War of the Worlds

In 1993, the notice on the mirror was a typically ironic comment on the dramatic changes in labor and technology that human body. This mirror in particular belongs to the beat-up minivan that Manny the Mechanic has been working on. Like all the other cars close to the tripods and their lightning storms, it has died, killed off by a massive electromagnetic pulse that has fried any electronics in the area. Before all hell breaks loose, Ray (Tom Cruise) tells Manny to replace the solenoid. This does the trick and makes the minivan the only functioning car in northern New Jersey. Ray steals the car, Manny resists him and pays the price.

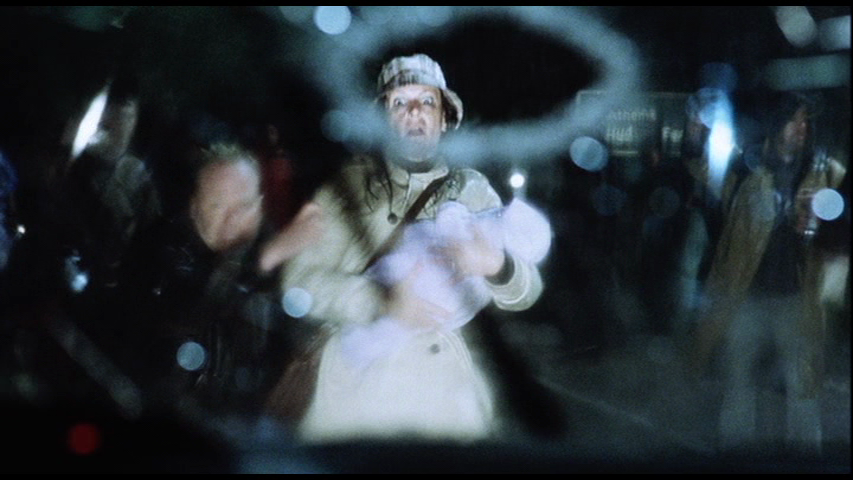

The tripod’s lethal rays begin to operate two scenes earlier, when Ray has gone looking for his own dead car. Like much of War of the Worlds, the scene is both incisive and incoherent. When Ray steps out into the street for a closer look at the tripod, a man is crouching in the foreground with a single use camera.

Figure 12. The Analog, War of the Worlds

We hear the shutter click; we see and even hear him manually winding the film: this is a last outpost of analog photography. That man, though, will quickly be replaced by another, this one armed with a miraculously functioning digital camcorder. (This is the incoherence.)

Figure 13. The Digital, War of the Worlds

Only then will the tripod begin zapping people, beginning with our cinematographer.

Figure 14. Digital Automatism, War of the Worlds

Once he is vaporized, the camcorder drops to the ground and we witness several evaporations through its viewfinder. The implication seems clear enough: digital capture is the threat; analog photography is a decidedly limited solution, but one the film clings to throughout.

In War of the Worlds the figure for photography is the punctured window. It first appears at the conclusion of a typically Spielbergian game of catch, in which Ray plays the bad dad to the hilt and his son gets his revenge by refusing to catch the ball, allowing it to sail cleanly through the pane behind him.

Figure 15. Spielbergian Catch, War of the Worlds

The ocular hole in the frame will find its nether analogue in the hole through which the alien is inserted into the subterranean tripod and out of which the tripod will emerge.

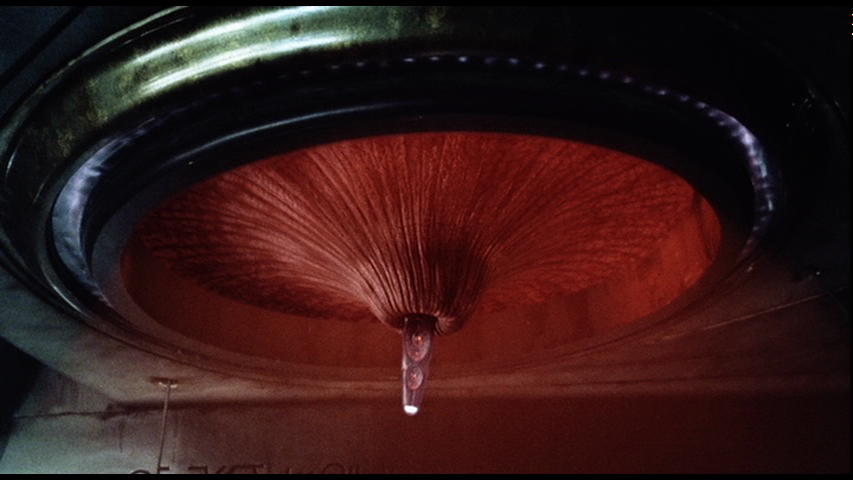

Figure 16. The Nether Analog, War of the Worlds

This truly Jersey-City-scaled pothole is a sort of cloacal maw, like the one on the tripod’s underside into which Ray will be ingested, only to deposit the hand grenades that will bring the craft down.

Figure 17. Cloacal Maw, War of the Worlds

The ocular hole, though, recurs, linked to the human-scaled automobile. Through this hole Ray will see, and nearly hit, a woman with a baby.

Figure 18. The Anti-Family Car, War of the Worlds

Later, and through another hole in a car windshield, he will see his daughter, Rachel, be swooped up by one of the tripod’s tentacles.

Figure 19. Oculus I, War of the Worlds

Throughout, the puncture is the force of indexicality; it registers both its affective (here, familial) bond and its social danger, as when the desperate ferry passengers smash and tear their way into the minivan, even if that means shredding their hands on the glass.

Figure 20. The Photographic Puncture, War of the Worlds

The hole, then, volatilizes the ready analogies between window and movie screen without risking the vaporization or dematerialization of the body. The mob’s invasion of the car, like the car’s mobility through the stopped traffic on the highways or even its potential collision with another person is fundamentally reassuring: it asserts a social connection and a bodily materiality at the heart of this particular interface. When the tripod scoops you up to eat you, that is horrible but, as it turns out, survivable; when you are vaporized, there is no solution.

Here, I am again relying on Rodowick’s account of the effects of “digital imaging” on photography. As digital imaging replaces photography, “transcription” is replaced by “digital capture” and “digital synthesis.” The digital “image” then redefines the nature of photography as the automatic recording of perceptually realistic images. In the process, both the time and the space of the image change. Here is Rodowick: “It is as if the creation of digital imaging as a medium were willing the annihilation of past duration with respect to space in order to replace it with another conception of time, that is, the time of calculation or computer cycles."[3] What Rodowick’s distinction allows us to do is to attach the differences in medium to a particular history, and, to reiterate, the claim I am making is that in these particular projects, that history is consciously being thought through.

That history reaches another inflection point in Abrams’s 2009 Star Trek reboot. There, Kirk is the relay between fascination with analogue, scalar models and digital production values. While troubled manchild Kirk nurses his wounds and considers Pike’s suggestion that he enlist in Starfleet, he casually picks up a starship saltshaker and twiddles it, inspecting its potmetal imperfections and its die-cast residues.

Figure 21. Starship Saltshaker, Star Trek

Behind him, almost lost in the bokeh, an LED screen pixellates in Abrams’s trademark blue. Kirk’s lack of interest in the screen suggests that the model is his proper focus. The next scene will find him riding his motorcycle to the spaceport, past some very Iowan cornfields, and gazing up at the still-under-construction Enterprise. Kirk’s interest in the model makes this Enterprise less synthetic: the saltshaker’s materiality spills over into the rendered ship.

The teaser trailer had managed the same transition slightly differently. Beginning with Lewis-Hinean shots of welders, it segued into recorded snippets from the glory days of the US space program, fragments with the crushed dynamic range of 1960s transmission and recording technology and long echoes that suggested the vastness of the mission. Leonard Nimoy’s voice then took us through the TV series’ opening—hinting at the importance that “old Spock” would play in the film—as we recognized that our shipwrights have been building the Enterprise. The tagline was simple enough: “Under Construction. Christmas 2008.” (The writers’ strike and Paramount’s near financial collapse delayed the opening until May 2009.) What the film managed through Kirk’s gaze, the trailer accomplished through Spock’s voice: the trailer erects an analogy between the real and the fictional space programs so smooth that it barely functions as analogy anymore. It seems, in short, to be history, and as history, that suffusing analogy promises to heal the breach occasioned by the loss of the analog.

This last claim may seem so much misplaced emotion in the guise of a medium specific account. For the form of the claim—that a higher level, conscious, production-centered analogy replaces the analogue—I am simply abusing another formulation of Rodowick’s: “The criteria of perceptual realism are defined by analogy with photographic images without themselves relying on analogical processes.”[4] But for my conviction that this structure undergirds Super 8, I am relying, finally, on Abrams himself. This is how he described the situation to The Guardian:

I'm obsessed with things that are distinctly analogue. We have a letterpress in our office. There's an absolute wonderful imperfection that you get when you do a letterpress, and that is the beauty of it. The time that is put in setting the type and running the press, inking the rollers, all that stuff – that kind of thing is clearly an extreme example. But it's the beauty of the actual investment of time, and the amount of time that goes by lets you consider things that somehow, in a kind of weird osmosis or spiritual way, is somehow implicit in the final product. And that seems to not exist much any more.[5]

Abrams makes clear that digital pressure threatens not simply analogue filmmaking, but filmmaking that self-consciously figures its own systemic importance.

There are, according to the film, two model-builders in Super 8. One is Joe, who builds in his room, working from kits. He has been working on model trains, which are critically about their scales.

Figure 22. Model Trains, Super 8

Charles recognizes this and wants to blow up Joe’s train for his film on the assumption that a scalar substitution can stand in for the missing production value of the train crash. The other modeler is Cooper, the alien, who has hidden out under the town water tower, stripping parts from cars and microwave ovens in order to turn the tower itself into a huge electromagnet that will attract the parts of his ship. Joe’s models are strictly analog: each part must look like the part that it is, and while there is plenty of room for craft—“dry-brush technique”—each part will have its role to play in the overall assembly. In contrast, the alien’s models are built out of utterly interchangeable digicubes that will form themselves into whatever part they need to be.

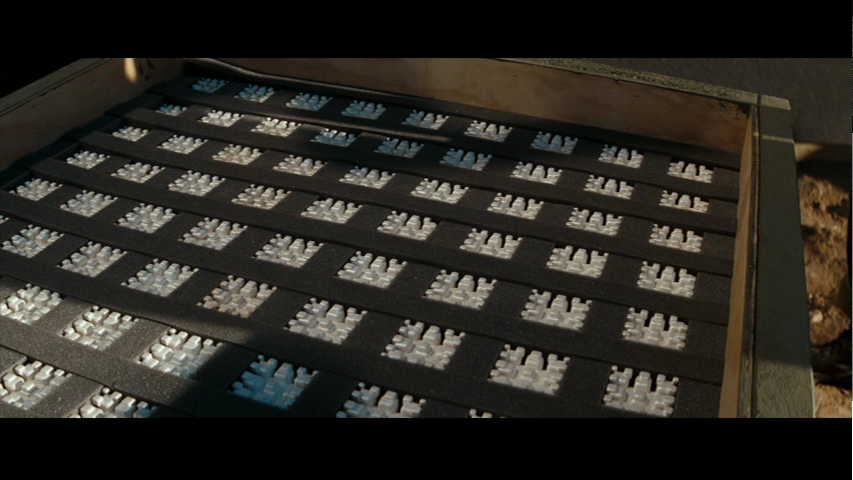

Figure 23. Digicubes, Super 8

They are the stem-cells of interstellar construction, and their quasi-cubic forms, when they are at rest, give no hint of what they might become.

Figure 24. Digicube Array, Super 8

In fact, these blank agglomerations of pixelblox (or sintercells) seem so different from Joe’s own work that we might wonder why, at the end, Joe asserts, “He’s building a model.” It is a line that makes even less sense given that what the alien is building is not a model but a real spaceship. In short, the gap between the analog and the digital is even wider in Super 8 than it was in Star Trek.

The link between Joe’s model and the alien’s appears when the digicube becomes restless and, eventually, shoots through the wall of his bedroom toward the water tower in the distance.

Figure 25. Through the Bedroom Wall, Super 8

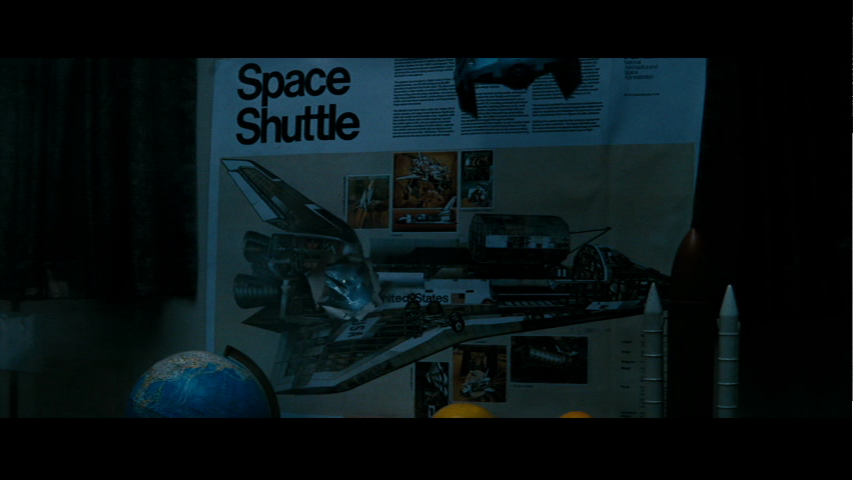

If we hadn’t noticed it before, this sequence highlights the model of Darth Vader’s tie fighter from Star Wars (an analog model of an analog film), a model that hangs in front of both a model of and a cutaway poster of the Space Shuttle. The two craft are mapped onto one another. The one suggests the analogue aspirations of Lucas’s advanced technological world. Star Wars had to look lived-in, built, and, by extension, buildable. The shuttle, in contrast, is state-of-the art. In 1979, the shuttle had not yet launched, much less blown up. But when Joe’s cube stirs to life and zings through the wall, it blasts a hole in the rear of the shuttle, foreshadowing the 1986 disaster and the death of Christa McAuliffe, a proleptic analogue of Joe’s own dead mother. What is more, the shuttle is clothed in quasi-pixels, those balky ceramic tiles that were, for years, falling off upon reentry. From the “dry-brush technique” of the train’s surface to the 2D pixelish surface of the shuttle to the 3D assemblage of the alien’s ship. Finally, and characteristically, the scene asserts the priority of the analogical in the punctured window shot that harkens back to War of the Worlds.

Figure 26. Digital Puncture, Super 8

Figure 27. Cubes and Tiles, Super 8

The kids refer to these things as “white Rubik’s cubes” a handy description that is both anachronistic—the Rubik’s cube came out the next year—and baffling: what would be the point of a white Rubik’s cube? It is not a puzzle since it has no solution. As an object of nearly limitless combinations, it suggests the essentially abstract and mathematical nature of digital imaging: a vast collection of combinations. At the same time, as a Rubik’s cube, it suggests an inherent manipulability, something we see in this masturbatory image. (The cube was a gift from Joe’s girlfriend, Alice.) And with that suggestion, we return to the notion that analogy takes the place of the analog. Where Charles wants to blow up scale and replace it with production value, Joe and Alice understand that when the digital becomes manipulable, it offers the possibility of descaling.

Super 8 opens with a shot of the interior of the “Employee Owned” Lillian Steel mill centered on a sign that declares that the facility has been accident-free for 784 days. As the camera pushes in on the sign, a hard-hatted worker rises on a scissor lift, removes the decidedly analog numbers, and replaces them with 1.

While this worker is, in effect, announcing an accident, he is also reducing the number by nearly three orders of magnitude. One day, one accident, and, as it turns out, one particular person who has died and one particular person who is left. The next sequence takes us to the wake for Elizabeth Lamb, making it clear that the accident has been fatal, that the victim was a woman, and that the town has come together in mourning just as it has at some earlier point come together to take over the mill. Charles’s parents discuss the fallout for Elizabeth’s son: “She was everything to him.” “Jack’s going to step up. He’s a good man.” “But he’s never had to be a father before. I don’t think he understands Joe.”

It is a piece of high Spielbergian family drama, with its distant father/ingenuous son dynamic. And while it seems a world away from the opening shot, it is actually a version of it. Like the hard-hatted worker, Jack is going to have to “step up” and focus on his son. That story, as Super 8 tells it, is fairly rudimentary, it has a nadir—when Jack explains that he is sending Joe to baseball camp for the summer—and it culminates in a remarkable fight.

To understand this properly, I think, we have to see it as the resolution of their conflict, not as its deferral. When Jack calls Alice’s father a “selfish son of a bitch,” he does not yet know that he is talking about himself. But when he goes through the process of descaling, he does. His declaration that there are “12,000 people in this town who are scared out of their mind. They’ve got one person to rely on. It used to be someone else, but now it’s just me.” is too close an analogy. Joe drops open his mouth and Jack scans his face. In that look, Jack is realizing that the substitution the entire town had to make is, in fact, the one his son must make. Now, they are clear.

Descaling, at the mill and at the Lamb’s house, is a way of reasserting the essential balance between the obligations of one’s work and family, or of one’s labor and one’s love, now channeled through the work of and a rivalry with, a paternal director. Let’s take this last notion a step further. Joe’s aggressive assertion of dependence is what is required to force his dad to recognize his own obligations. And understood affectively, it threatens to plunge us into a dead-end “anxiety of influence” reading of the film. Abrams, characteristically canny, explained why he did not think that was the proper model.

"The initial conceit was not 'do a Spielbergian movie,'" Abrams says. "I didn't think: 'Oh, let's start ripping off other Spielberg films.' It was just: 'This is a story that could be cool.' "I'd called a guy who had a production company called Amblin, who made a bunch of movies that I loved [when I was] growing up and still love now, and when you're working with someone who inspires you in a certain way, that's part of the fun of it. "Super 8 is about kids in 1979 who are the age that I was at that time, and I was massively influenced by Steven's films. What made perfect sense was not: 'OK, let's ape his movies and start copying things,' but let's make a movie that feels like it belongs on a shelf with other Amblin movies. "It was a spirit, not a scene, that I was trying to emulate. It felt like: 'This is what the movie wants to be.' I would actually say that because I was doing it with Steven, I felt entirely liberated to embrace that kind of stuff. I never would have made this movie this way, I'm certain, had he not been a producer."[6]

On the one hand, this assertion of corporate allegiance merely expands the field of potential thefts to include the work of Robert Zemeckis and Joe Dante. But on the other hand, it is an assertion of utopian collective aesthetic production. The film can be Abrams’s because it is a corporate property. Had it been made outside of Amblin, Super 8 would be a ripoff or an homage; inside it is an aspirational aesthetic object. It wants to sit on the shelf; “this is what the movie wants to be.” By 2011, the distance between digital imaging and scalar modeling seems too great to be stably mediated by an individual body, even the body of the auteur. In his place, we find an employee-owned corporation, a fantasy of a studio.

Notes

[1] “The Making of Jurassic Park,” Jurassic Park, directed by Steven Spielberg (1993; Universal Studios Home Entertainment, 2010), DVD.

[2] Rodowick, The Virtual Life of Film, Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2007, 122.

[3] Ibid., 104.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Katie Puckrick, “J.J. Abrams: ‘I called Spielberg and he said yes,” The Guardian, 8/1/11, http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2011/aug/01/jj-abrams-spielberg-super-8.

[6] Ibid.

J.D. Connor is Assistant Professor in the Department of History of Art at Yale University. He is currently completing The Studios after the Studios: Hollywood in the Neoclassical Era, 1970–2005. Prof. Connor is also a member of the steering committee for Post45, a group of scholars of American postwar literature and culture. www.post45.org

Media Fields Journal

Media Fields Journal