Remembering Bhopal: Situated Testimony, Chronic Disaster, and Memories of Survival

by Rahul Mukherjee

[ PDF Version ]

A lethal gas leak occurred in the Methyl Isocyanate (MIC) plant in Bhopal on the third of December, 1984. The disaster resulted in thousands of deaths and precipitated unimaginable long-term effects, including birth disorders, breathing problems, and other ailments for injured victims. While revisiting the original disaster event is important, it needs to be acknowledged that Bhopal is a chronic disaster with continuing effects on the lives of victim-survivors. Because of inadequate compensation from corporations involved (Union Carbide and Dow Chemicals) and the Indian Government’s indifference to their “social suffering,”[1] survivors still have to negotiate on a daily basis their lack of access to clean drinking water and the paucity of resources for medical treatment.

The complexities of the gas disaster—the interrelated legal, political, infrastructural, scientific, social, and psycho-cultural issues with regards to its occurrence and unfolding, its immediate aftermath, and its continuing effects—make the attempt to represent, remember, mediate, and sense the disaster particularly difficult. What should one remember about Bhopal and how should one remember Bhopal?[2] Documentaries like Seconds from Disaster: Bhopal (dir. Russell Eatough, UK, 2011) and One Night in Bhopal (dir. Steve Condie and BBC, UK, 2004) focus on reconstructing the set of events that led to the disaster through scientific modeling and dramatic reenactment of the events told from the perspective of experts and survivors. In Litigating Disaster (France/US, 2004), filmmaker Ilan Ziv follows attorney Rajan Sharma as he attempts to put together legal evidence required to try Union Carbide in an American Court. In the context of the disaster, in which transnational corporations, courts, and bureaucratic bodies have repeatedly made legal demands on victim-survivors to present scientific evidence of their medical injuries and Carbide’s toxic role,[3] these films seem to rise to that challenge.

Reconstructing the disaster through its scientific and legal explanations is necessary, but it might lead to obscuring other ways of comprehending the disaster. The use of scientific and legal explanations also risks further marginalizing victim-survivors who may be unable to articulate their comprehension of the disaster in the vocabulary of mainstream science or legal discourse. Fusing subjective memories of victim-survivors with scientific-legal evidence can be challenging in documentaries, for as Arthur Kleinman, Veena Das, and Margaret Lock have contended, “technical rationality excludes other forms of knowledge and practice by generalizing, quantifying, and in a word, normalizing experiences (collective and personal).”[4]

Going beyond the primal moment of the disaster and its reconstruction to instead emphasize the minute traumas that survivors have to suffer every day, and the creative responses that they have developed over the years, could also be a way of remembering Bhopal. Here remembering is constituted by not the memory of a spectacular disaster event but the memory of survival, a survival marked by vulnerability.

In this paper, I will focus on specific instances to be found in the documentaries related to the Bhopal Gas Tragedy, where the processes of remembering and mediation unfold in particular places. I argue that tracing the “material-discursive”[5] relations between the bodies of disaster survivors and spaces like the abandoned Union Carbide factory precinct and the Hamidia Hospital (where survivors were treated) among others, plays a particularly effective role both in remembering the horrific disaster event and in accounting for the disaster’s chronicity along with its uncertain future potentialities. I begin with a discussion of staging witnesses and recording testimonies in Litigating Disaster and One Night in Bhopal to see how staged affective stories of survivors are intermingled with presentations of scientific-legal evidence. Following this, I go on to discuss briefly a recent documentary Bhopali (dir. Max Carlson, US/India, 2011) that not only categorically and explicitly recognizes that the Bhopal Gas Tragedy is a chronic disaster, but depicts it as one giving due emphasis to the process and memory of survival.

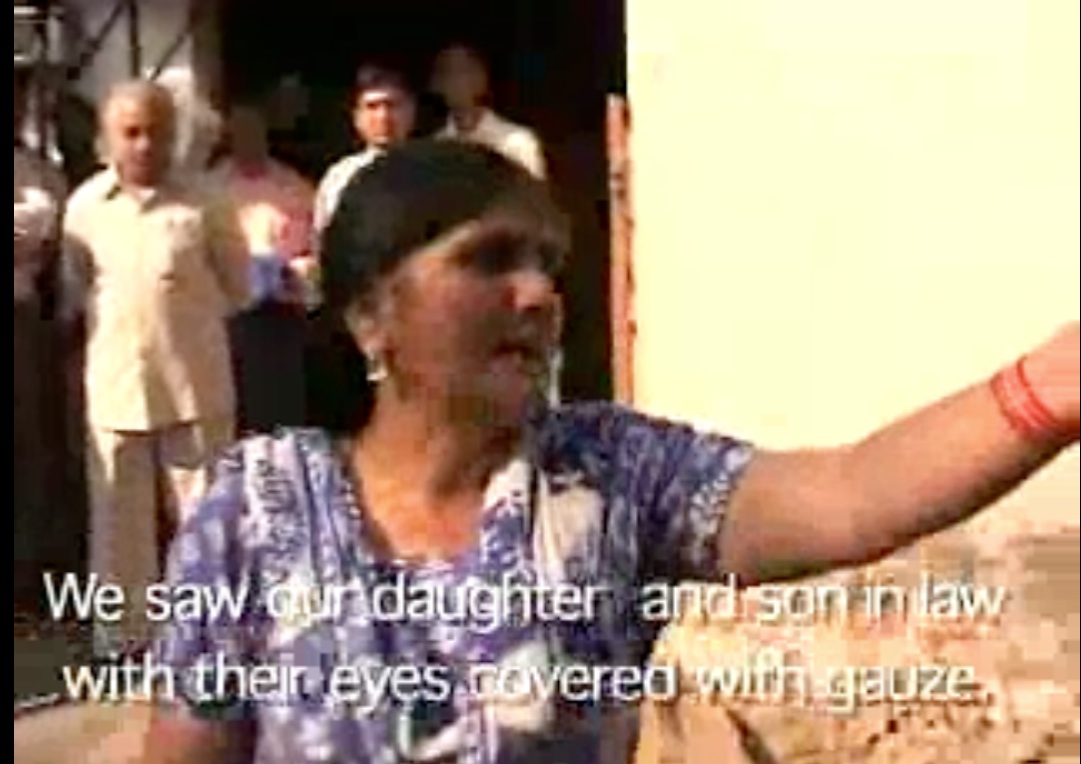

Litigating Disaster uses witness testimonies as legal and historical evidence in a yet-to-exist court of law in order to reveal the corporate negligence of Union Carbide. The opening section of the film recreates what happened on the fateful night of the disaster through archival footage and the personal accounts of witnesses. The testimonies are taken in Bhopal, where disaster victims continue to live. Hamida Bi walks towards the camera with the caption “Hamidia Hospital, 2004” in the top right corner of the frame. In the next shot, the camera follows her as she relates what happened during the night of December 3, 1984 at Hamidia Hospital, where she had come to look for her daughter, son-in-law, and grand-daughter (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: Hamida Bi approaches the Hamidia Hospital in 2004. Source: Screen Capture from Litigating Disaster

Figure 2: Archival footage of covered dead bodies lying in Hamidia hospital in 1984. Source: Screen Capture from Litigating Disaster

Gesturing with her hands as she is speaking, Bi says: “As we got out of the hospital we were crying. Hindus and Muslims were both collecting bodies from the doctors. Both their bodies were catalogued with doctors giving numbers and then they would take them away in jeeps and other vehicles.”[6] As Bi narrates what she saw, she motions with her hands, attempting to enact how she saw people carrying the dead bodies. The next shot is archival footage from December 1984 of the Hamidia hospital cordoned off by police amidst a crowd of onlookers and dead bodies (See Figure 2).

Over the archival footage, Bi’s voice continues, “The moment we entered the gate, we started looking at dead bodies and there were bodies all over.”[7] The archival footage transitions into present scenes of Bi once again walking and moving her hands faster than before. Her voice chokes with emotion as she describes how she continued to look for her son-in-law and daughter but could not find them. Archival footage is again layered over her verbal descriptions before we next see her recounting how, tired from looking and crying, she saw some people sitting at a particular place where she also eventually found her son-in-law and daughter. She points with her hand to that exact place outside the hospital saying, “This place down there.”[8] Once again, Bi describes the action through hand motions, bringing both her outstretched hands towards her eyes to stress that her son-in-law and daughter’s eyes were covered with cotton pads.

Bi then makes a cloth-wrapping motion with her hands as she describes how her then-still-alive granddaughter was covered in a wet sheet and left near the water tank. She points this time to where the water tank was, and though we do not see where she points, we see present day onlookers in Hamidia hospital with their solemn, tense stares, and then more archival footage of dead bodies being loaded into trucks, video of mothers breaking down from grief, and babies with stitches and bandages on their heads (See Figure 3).

Figure 3: Hamida Bi points to the water tank. Source: Screen Capture from Litigating Disaster

Following Janet Walker, I understand “situated testimony” or “testimony delivered in situ” as testimony rendered “from the place where catastrophic past events—that generate the subject and subject matter both—occurred.”[9] Many gas victims were brought to Hamidia hospital for treatment and the MIC reaction in the bodies of affected people was so rapid that many just perished in the hospital; thus the swarm of dead bodies lying all over that Bi remembers. Bi gives a “situated testimony” as she recounts the events of the night of the disaster at Hamidia hospital, the very same place where she had seen them unfolding. Litigating Disaster also stages “situated testimony” with a walking Bi put into a scene (mise-en-scène) outside the Hamidia hospital.[10]

The emptiness of the New York district courtroom (repeatedly shown throughout Litigating Disaster) signifies that survivors have been excluded from testifying in official legal spaces (See Figure 4). The survivor testimonials, staged and recorded now at key sites of disaster, emphasize the geopolitical asymmetry, an asymmetry that Union Carbide was able to exploit by setting up factories in so-called Third World outposts where accountability laws were relaxed. Additionally, the movement from the court to the disaster sites helps to highlight the everyday problems faced by survivors living in Bhopal even if Union Carbide has abandoned it.

Figure 4: Empty Courtroom in New York. Source: Screen Capture from Litigating Disaster

Writing on reenactment in Rity Panh’s S-21 : The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine, Deirdre Boyle notes how Panh is able to “summon traumatic memory by repeatedly exposing both perpetrators and victims to the site of trauma.”[11] Boyle also notes how the body and behavioral expressions can be seen to be conduits/surfaces through which manifestations of trauma can be observed. For spectators watching Bi’s in situ testimony in Litigating Disaster, the sheer physicality of her traumatic memory is on display in her brisk walking, her bodily gestures, the constant motion of her hands to give form to the actions she witnessed, and in her repeated pointing to specific places where she encountered her family members. Bi’s embodied memory adds to the truth-ness of Ziv and Rajan’s presented visible evidence for, as director Panh notes in an interview, “. . . the memory of the body never lies.”[12]

Writing about documentary representations of historical events, Robert Rosenstone notes that archival footage, when used, only gets included as “selected images of those events carefully arranged into sequences to tell a particular story or to make a particular argument,”[13] and thereby cannot be equated to the event or the experience of that event. Clearly, Ziv selects only the archival material that goes along with Bi’s story. Additionally, Bi’s personal story is one of searching for her family members, while the periodically intercut archival footages presented of the hospital tell a more general story.

There is certainly a disconnect between re-presented images from the past and Bi’s present-day testimony here, and yet through juxtaposition, the audiovisual coverage of situated testimonies and the presented archival footage actually supplement and nourish each other. While archival footage lends credibility to Bi’s personal story of traumatic loss, Bi’s recounting brings the richness of personal experiences that Rosenstone sees as lacking back into the archival footage. The documentary that itself plays a role in the social organization and transmission of collective memory, by moving back and forth between archival footage and Bi’s testimony, is able to show how personal memory has the potential to influence the historical record of events like the gas disaster. Bi’s hand pointing within the space of documentary representation, when cut together with images from the past, becomes not only a way of visualizing movement across the space of Hamidia hospital but also a way of visualizing movement across time—an invitation to the film’s spectators to travel twenty years back in time to when the disaster happened.

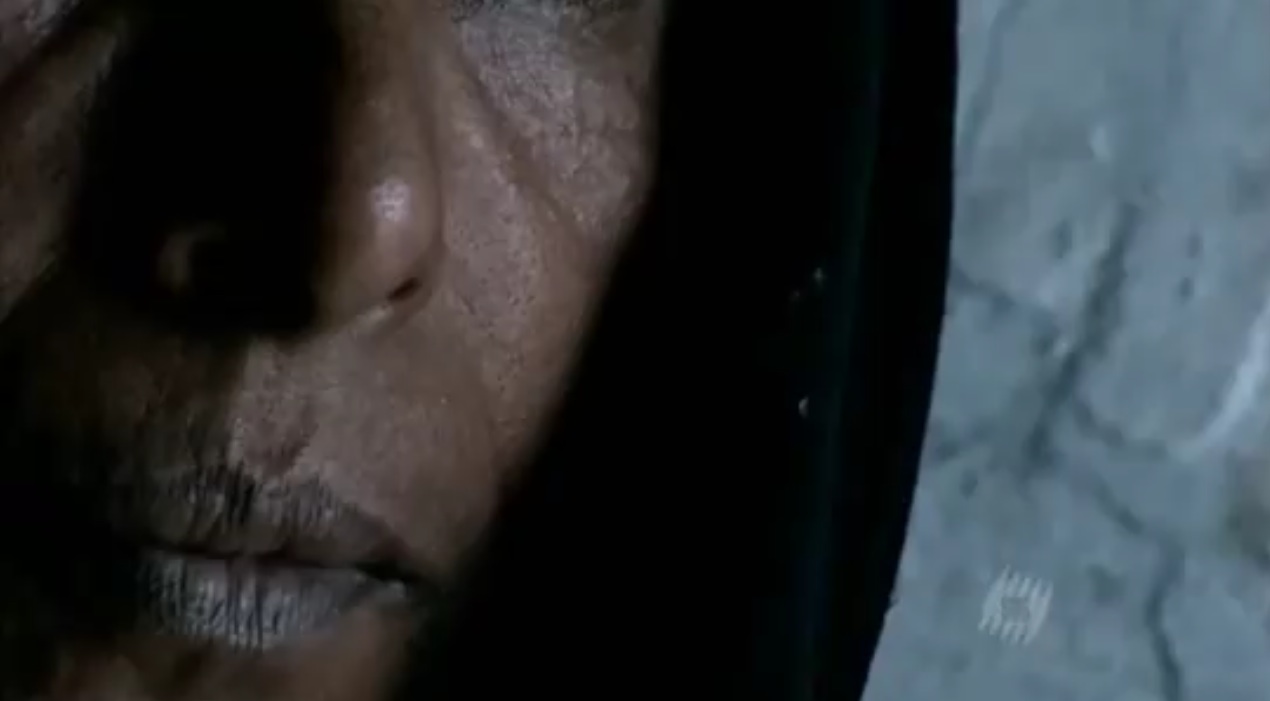

Steve Condie’s One Night in Bhopal reconstructs the disaster by weaving together testimonial accounts from five different witnesses: medical doctor Kumkum Saxena; company engineer Suman Dey, then working in the Carbide plant; Bhopal’s police chief at the time of the disaster Swaraj Puri; disaster victim Mehboob Bi, who lost her children and later her husband to the gas; and Shahid Noor, a young man orphaned by the tragedy. Condie shows the audience each of his five witnesses several times, but they do not themselves enact their roles or speak (with the exception of Swaraj Puri who seems to be playing both his present and past selves). Different narrative voices are assigned to each of the testifiers and these voices carry forward the storytelling process in the form of an interior monologue as we are shown the actual witnesses framed against a strikingly constructed mise-en-scène. Actual witnesses in the majority of the scenes are captured in a static pose, sitting or standing, looking towards the camera in some cases but most often forlornly towards an elsewhere, perhaps towards the disaster itself. Extreme close-ups frame the resigned faces of witnesses. At times Condie inserts an extreme close-up of just their one eye, their hands, or their lips filling the entire screen. This fragmentation is used to focus minutely on the gas-affected body parts of the victims: Mehboob Bi’s lips and hands, or the watering eyes of Shahid Noor, which he finds difficult to keep open. Even in dramatically-enacted scenes, the camera often moves from an extreme-close up of one actor’s face to another extreme close-up, creating a claustrophobic perception and unsettling the spectator as s/he needs to keep readjusting his/her focus, and at the same time lending the narrative a mysterious air.

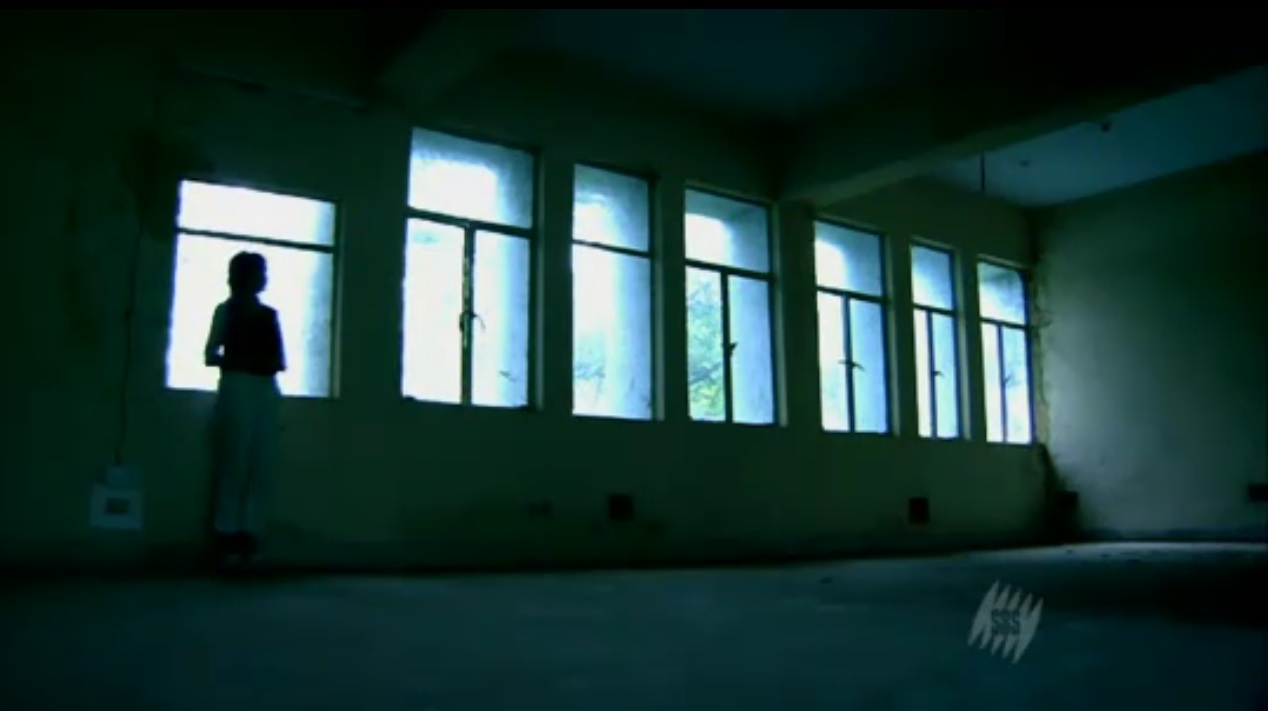

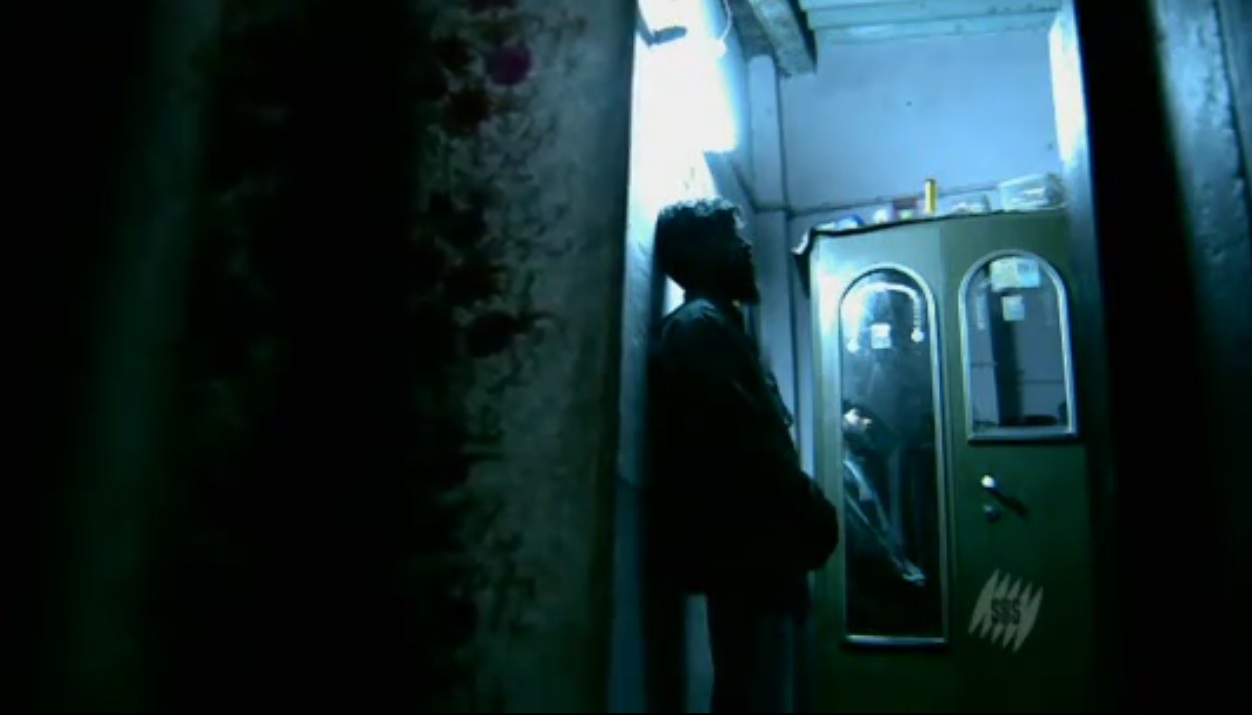

Figure 5 (Left): A worried Kumkum as partial light comes from the window and Figure 6 (Right): Effect Light above Shahid Noor. Source: Screen Captures from One Night in Bhopal

When one sees the witnesses in long shots, they are standing in dimly lit rooms with partial light coming from windows or an effect light over the social actor’s head (See Figure 5 and Figure 6). Whether in close-ups or long shots, witnesses occupy the edge of the frame (See Figure 5, Figure 7, and Figure 8). In addition to a mixture of gloom, mystery and foreboding, such a framing of witnesses makes the audience realize the testifiers’ vulnerability and marginality as they found themselves to be victims of circumstances then and now. Kumkum’s concern about the toxicity of MIC and her insistence on the need for evacuation plans in case of disaster are ignored by Union Carbide management. Mehboob Bi’s pleas to her husband Chand to stop working in Carbide are not heeded.

Figure 7 (Left): Extreme Close-up of Mehboob Bi's lips and Figure 8 (Right): Extreme Close-up of Shahid Noor’s tearful eyes. Source: Screen Captures from One Night in Bhopal

Such an aesthetic execution of reenactment helps the director to go beyond the limitations of archival footage to stage scenes which were formerly only in witnesses’ memories, and to fill those scenes with sound and images. Moreover, by showing the contrast between real witnesses now and their more upbeat and hopeful former selves then, the film evokes the sense of loss that the victim-survivors have suffered. As Shahid Noor reminisces, “My father had a degree. Today my children don’t go to school. They don’t even know to read or write. Our standard of living has gone back by fifty years.”[14]

Despite these effective outcomes of deploying a dramatized reenactment, Condie’s strategy neither to deploy the original voice of witnesses nor to use their performances in reenactment even while he continues to showcase them in spectacular mise-en-scène leads to two kinds of interrelated distancing. First, the distance of the witness (social actor) from the performer (trained actor), and by extension from the performance, increases. Second, the gap between the witnesses and the film’s spectators widens, as the witness appears to be an immobile and rich source of stories but not their enactor.

Psychoanalytical and sociological approaches to the study of pain and social suffering have stressed that at some point individual pain is incommunicable, and yet the incapability to understand and imagine another person’s pain does not stop us from acknowledging that pain.[15] Over the years, trauma and memory studies scholars have nuanced the idea of empathetic identification with the suffering of others. Susannah Radstone posits how memoirs may “invite multiple identifications not only with suffering, but with the voyeuristic or triumphalist observation of suffering.”[16] Elizabeth Cowie argues that documentary depiction of traumatic disaster events can generate audiences’ desire to put themselves in the place of social actors (survivors); yet for Cowie one must be cognizant of the limits of such identification because at times, “one gets the satisfaction of not being the social actor presented.”[17] Cowie adds, though, that identification closer to empathy also can happen, which requires identifying not with the social actor’s loss but “with her position in a narrative of loss,”[18] which includes the spectator’s own self and her own losses.

In integrating this academic scholarship with my discussion of the different ways of framing witnesses in particular spaces while recording testimonies in Litigating Disaster and One Night in Bhopal, I am not interested in qualitatively evaluating whether one documentary helps us to comprehend, acknowledge and identify with the pain of disaster survivors better than the other film. Such an exercise has a lot at stake but can be problematic, for spectator identifications can be diverse and audiences might respond to and interpret stylistic cues differently.[19] However, I do think that the strategy of using situated testimony interlaced with archival footage in Litigating Disaster presents to the audiences the connections between the embodied memory of the testifier Hamida Bi and the space of Hamidia hospital. We comprehend not so much the depth of the trauma of Bi, but the material-discursive configurations of the space of Hamidia hospital that summon Bi’s traumatic memory: her body’s relation to the hospital building, to re-membered bodies wrapped in white cloth, to stitches on the heads of babies, and to jeeps carrying bodies.

In invoking a material-discursive framework, I am hinting towards the literature in new materialism and feminist technoscience by writers like Karen Barad and Donna Haraway amongst others. Barad lays down the framework for “agential realism,” based on which practices are understood as “processes involving intra-action of multiple material-discursive apparatuses.”[20] Such an intra-action of different objects and subjects as part of a process “underscores the sense in which subjects and objects emerge through their encounters with each other.”[21] Therefore subjects and objects are not determined prior to their interaction. Thinking of the relation of “situated testimony” with “embodied memory” within this framework offers the opportunity to see the generation of affect—in this case, the affect gets generated as Bi moves across the material space of Hamidia hospital.

Maintaining that both “affect” and “emotion” are “intensity” but pertain to different orders and follow different logics, Brian Massumi compellingly clarifies the difference between the two, noting that if “emotion” is “qualified intensity” that can be “owned and recognized” and has “subjective content,” affect has an “irreducibly bodily and autonomic nature” and thus is not easily recognizable.[22] The awakening of embodied memory in Hamida Bi in the first instance is because of the affective sensation felt by her as she is put in relation to (intra-acts with) the material space of the Hamidia hospital. The sensation soon manifests itself as an emotional memory that can be signified, and yet the intensity of the affective sensation, which triggered such an embodied memory, might escape mediated representation. Just like the incommunicability of pain, experience at the level of sensation also might elude signification, even as both seem to contribute at different levels toward embodied memory.

In One Night in Bhopal, the spectacular framing of witnesses does not quite afford such an understanding of material-discursive relations. Even as the testifiers are often framed in actual locations in Bhopal, the use of effect lighting, color correction, and change of (camera) focus to showcase these spaces serve to suggest that mediated spaces and social actors share feelings of despair. Even as these spaces provide a context for the actors’ actions and situations, they get deployed to heighten the drama of such despair.

In Bhopali, Carlson chooses to represent the continuing effects of the disaster. The gas leak event and the build-up to the disaster, which are foregrounded in One Night in Bhopal and Litigating Disaster, are not given much screen time in Bhopali. Carlson was interested in the personal stories of survivors but did not want them to be merely “technical” or “informative” anecdotes that fit together to reference an authentic originary moment. In his “telling of the film Bhopali,” Carlson mentioned in a conversation, the point was “to not make it technical or historical but to make it told through the eyes of . . . certain survivors and people I met like Sanjay and Saiba’s family, like some of the kids in the Chingari Trust.”[23]

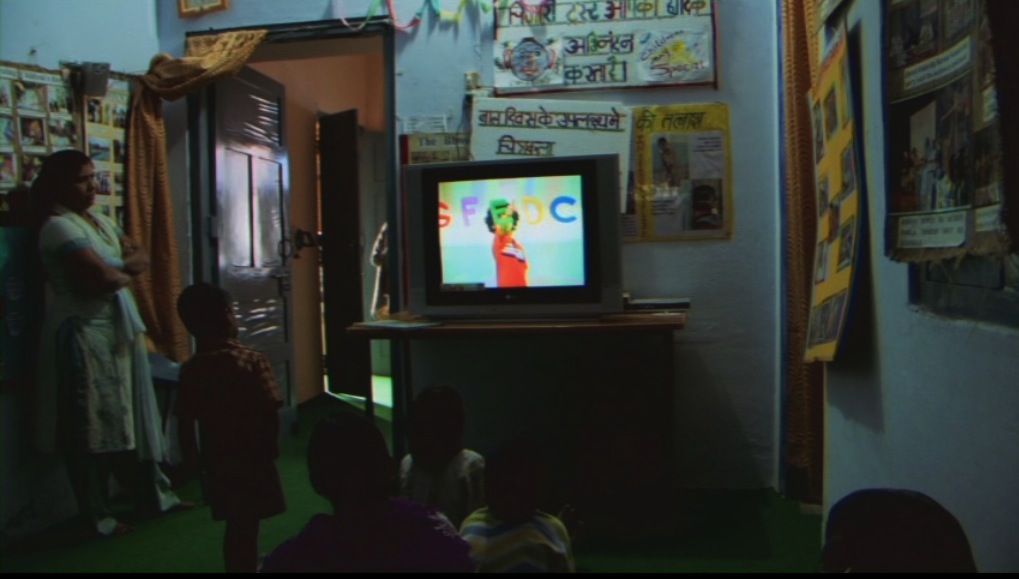

The story of the institution of Chingari Trust, where kids with congenital birth defects or suffering from diseases related to water contamination are treated, is narrativized by following kids as they are picked up early in the morning from their homes in the gas affected area in vans and brought to the Chingari trust office (See Figure 9 and Figure 10). Saiba, one of the kids suffering from such a disorder is shown to be treated in Hamidia hospital. Carlson chanced upon Saiba and her family’s story because they happened to live across the street from where he was staying. Saiba’s father sold candies and Carlson found himself buying candies one day and conversing with him, and upon learning about Saiba’s health, taking her to the hospital. I do not want to indulge in spatial determinism here but Carlson’s documentary is what it is partly because of the particular organizational spaces that he decided to inhabit—Sambhavna Clinic and Chingari Trust are spaces of advocacy for alternative futures, allowing him to come in close proximity with survival narratives.

Figure 9 (Left): Bhopali Children in Chingari Trust Van and Figure 10 (Right): Children at Chingari Trust. Source: Screen Captures from Bhopali

These survival stories grow organically in the film and some of them (like Saiba’s anecdote) are marked by contingent encounters as elaborated by Carlson. The unfolding of events in Bhopali suggests a piling up of memories of miseries that are routine, and that seem to have received less attention in many other documentaries precisely because of this routine-ness. This memory has a cumulative (along with a recurring) nature: as audiences, we find out that Sanjay Verma’s story of growing up under the shadow of disaster begins in December 1984 as a six-month-old baby, following which he spends time in the orphanage and then starts living with his sister and brother in the Gas Relief Colony (only to lose his brother soon to paranoid schizophrenia there). In 2004, he decides to join the advocacy movement for Justice in Bhopal and starts translating for journalists and filmmakers. The revealing of this memory of survival is hardly chronological or linear in the documentary, as Verma’s role in the film is largely as Carlson’s guide through Bhopal, over a period of about two months.

The emphasis on children of Bhopal like Verma and Saiba in Carlson’s documentary brings to mind Marianne Hirsch’s concept of “postmemory,” but with some crucial caveats. Hirsch describes postmemory to be “a structure of inter- and trans-generational transmission of traumatic knowledge and experience.”[24] Like postmemory, the connection of these children to the disastrous past is indeed “not mediated by recall” but by “imaginative investment, projection and creation.”[25] And yet in this act of imagination, one would have to factor in the role of the oppressive (and continuing) presence of the toxic environment within which the children grew up—an environment bequeathed to them by the disaster and Union Carbide India Limited’s careless waste disposal. The irony is palpable when one thinks that the children everyday see the Carbide plant that caused the disaster, and they are in fact shown in Bhopali to be playing close to the plant—their material-discursive encounters with the plant thus are proximate and oddly familiar (Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Figure 11 (Left): Children playing close to plant and Figure 12 (Right): Drinking water problems due to groundwater contamination. Source: Screen Captures from Bhopali

How is postmemory changed when the second-generation survivors not only have to grow with the “overwhelming inherited memories” but also with inherited (genetically transmitted) toxic chemicals in their bodies? These chemicals have a life of their own; they undergo mutations over time too, participating in slow reactions. The chronic toxicity caused by these chemical substances like mercury and chromium to the Bhopal survivors as they get repeatedly exposed to them in small amounts everyday parallels in strange ways the chronic nature of the Bhopal disaster.[26] One yearns for a documentary that recognizes that the act of remembering Bhopal is incomplete without a poetics of how these toxics inhabiting the bodies of victim-survivors are (and have been) eventful, and how the bodies’ long and intimate (albeit forced) relationship with these toxins generates enduring memories and can (potentially) spring uncertain futures.

Notes

[1] I am borrowing the term as used in Arthur Kleinman, Veena Das, and Margaret Lock, “Introduction,” in Klienman, Das and Lock, eds., Social Suffering (Berkley: University of California Press, 1997), ix-xxvii.

[2] Peter Burke further expands these questions by remarking: “who wants whom to remember what, and why?” Burke is concerned about how “memory communities” involve collective co-construction of memory and such a memory can be based on strategic considerations of the present. See Peter Burke, “History as Social Memory,” in Varieties of Cultural History (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997), 56.

[3] See Veena Das, Critical Events: An Anthropological Perspective on Contemporary India (Delhi: OUP, 1995), 19.

[4] Kleinman et al., xx.

[5] I am borrowing this concept from Karen Barad’s work and shall elaborate on it later in this paper. See Karen Barad, “Reconceiving Scientific Literacy as Agential Literacy Or, Learning How to Intra-act Responsibly within the World,” in Rodney Reid and Sharon Traweek, eds., Doing Science + Culture (Routledge: NY and London, 2000).

[6] Excerpt from Litigating Disaster.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] See Janet Walker’s essay on on-site testimonies of catastrophe survivors shot in New Orleans as part of video-footage and finished documentaries made following Hurricane Katrina. Janet Walker, “Rights and Return: Perils and Fantasies of Situated Testimony after Katrina,” in Bhaskar Sarkar and Janet Walker, eds., Documentary Testimonies: Global Archives of Suffering (New York and London: Routledge, 2010), 84.

[10] Walker also clarifies that merely because one is looking at a situated testimony in a documentary, one cannot be allowed to think/feel that the testimony is totally unconstructed—the walking testimonial involves mise-en-scène. Ibid., 85.

[11] Deirdre Boyle, “Trauma, Memory, Documentary: Reenactment in two films by Rity Panh (Cambodia) and Garin Nugroho (Indonesia),” In Bhaskar Sarkar and Janet Walker, eds., Documentary Testimonies: Global Archives of Suffering (New York and London: Routledge, 2010), 158.

[12] Ibid.,159.

[13] Robert Rosenstone, Visions of the Past: The Challenge of Film to Our idea of History (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1995), 35.

[14] Excerpt from One Night in Bhopal.

[15] Kleinman et al., xiii.

[16] Susannah Radstone, “Memory Studies: For and Against,” Memory Studies 1, no. 1 (2008): 31-39, 34.

[17] Elizabeth Cowie, “The Spectacle of Actuality,” in Jane M. Gaines and Michael Renov, eds., Collecting Visible Evidence (Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 31.

[18] Ibid.

[19] For example, I have already mentioned the distancing effect created in One Night in Bhopal, and yet the re-enactment and deployment of voices in English might have made the film more palatable for a Western (British) audience.

[20] Barad, Reconceiving Scientific Literacy as Agential Literacy, 234.

[21] Lucy Suchman, “Reconfigurations,” Human-Machine Reconfigurations: Plans and Situated Actions. 2nd Edition (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 267.

[22] Brian Massumi, Movement, Affect, Sensation: Parables for the Virtual, Duke University Press: Durham and London, pp.27-28, 2002.

[23] Excerpt from an interview with director Max Carlson, 7th April, 2012.

[24] Marianne Hirsch, “The Generation of Postmemory,” Poetics Today, 29, no. 1 (2008): 103-128, 106.

[25] Ibid.,107.

[26] In Bhopali, the space of the Carbide plant is mediated not only to teach viewers about the exothermic reaction of Methyl Isocyanate and water that caused the gas disaster, but also to inform them about the present and future effects of the toxic compounds left in the still-uncleaned Union Carbide factory premises. Verma takes Carlson to show the solar evaporation pond where Carbide wastes were disposed. The waste disposal strategy was inefficient and inadequate. Center for Science and Environment spokespersons in the film mention how toxic mercury and chromium are finding their way from this pond into groundwater sources, separated as they were by only a thin line of plastic covering. In the process, this toxic waste is contaminating the only drinking water source available to the survivors.

Rahul Mukherjee is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara with graduate emphases in Global Studies and in Technology and Society. Highly passionate about critical/cultural theory and science and technology studies, his research interests include documentary, databases, and public cultures of uncertainty. Rahul's dissertation project involves exploring mediated technoscience debates.

Media Fields Journal

Media Fields Journal