Scaling Michelangelo

by Anthony Metivier

[ PDF version ]

Scaling Michelangelo

“How richly they deserved to be carved bigger than life …”[1]

In the 1961 novel The Agony and the Ecstasy, Irving Stone hammers out a larger than life portrait of Michelangelo in eleven chapters, including a twelfth ghost chapter in the form of an extensive bibliography that attempts to validate elements of the real Michelangelo biography embodied by the fiction. At the level of the sentence, each blow in Stone’s novel tells us just how much the suitably named author feels Michelangelo deserves the literary portrait. The girth of the novel, at 776 pages in Signet’s 1987 softcover reissue, physically matches the book as object with Michelangelo’s own concerns. Whereas the novelist uses paper for the molding of Michelangelo in prose, the artist assigns marble to “displace space”[2] in order to bring Biblical characters and narratives into the world.

Carol Reed’s 1965 film adaptation of The Agony and the Ecstasy selects Stone’s penchant for metaphors of size and scale in a number of ways – and if success can be measured in statues, even small ones, then it is worth noting that the film was nominated for five Oscars, but awarded none. Both novel and film focus on the scale of Michelangelo’s works, while contending with the size of his ego. Each presents a fundamental tension between the status of enormous genius and the questions human brilliance inspires. Does the manifestation of exquisite talent come from the immeasurable fount of God, or does it stem entirely from human skill? And in either case, to what extent does the bulk of the Papal States weigh against the frail individual in order to produce great art with or without God’s behest?

Yet the film deals with these questions in a manner much differently than the novel, even though they both pursue Mosaic themes. Whereas Stone embeds these in a wide series of archetypes associated with the stubborn genius, the film adaptation squeezes Michelangelo into the conventions of the Biblical epic, action and disaster movies and the gladiator genre, each of which is characterized by huge reproductions of buildings and spaces that constitute Hollywood’s notion of the ancient world. Whereas the novel presents Michelangelo’s life in stages as he develops as an artist in terms of both skill and concept, the film introduces Michelangelo in full swing, focusing not on artistic development, but on the conflict between his will and Julius II’s motivations, which are presented as perverse and shady, even though the film’s audience knows all along that they will culminate in the grandeur of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. In terms of film convention, Julius II proffers a series of escalating oppositions that Michelangelo must surmount with the aid of divine insight that seeps from a painted expanse of studio sky.

Adaptation and Documentary

Before dealing with the film further, we must acknowledge that Irving Stone’s novel is itself a kind of adaptation, and, as previously mentioned, Stone makes sure to let us know the heft of his research with academic precision, in the form of an elaborate bibliography at the end of the book, along with an explanatory note detailing the extent of his travels for material, as though conquering geography were itself a valid means of authentication. (And it may well be, given the path Stone seems to have laid for tourist readers of his book who could track his passage long before The Da Vinci Code made such tours based on art novel-films a fad). Stone speaks of consulting entireties: the complete letters of Michelangelo, the complete poems, the most authoritative historical biographies. We should note by contrast that more recent novelists who have tapped painters from the past for their fiction have been more modest in their approach. Tracy Chevalier and Susan Vreeland, for example, list only two titles each for their imaginative renderings of Vermeer and his world in Girl with a Pearl Earring and Girl in Hyacinth Blue respectively.

However oddly, Reed’s film also shows off a certain depth of research by opening with a relatively long, but spiritedly scored documentary dedicated to showing the surviving Michelangelo sculptures as they could have been seen by American tourists when the film was released. If Michelangelo’s art is supposed to be universal and eternal, the documentary suggests, it must be so at the price of being surrounded by parking lots, electrical towers and apartment buildings. We see the museum of ancient arts is buried in the surrounding entrapments of life in the 1960s.

Figure 1: The Façade of St. Peter’s Basilica surrounded by a parking lot and historically dated automobiles.

Figure 2: An electrical tower and apartment buildings surrounding St. Peter’s Basilica show us just how much time has passed since Michelangelo completed his now beloved works.

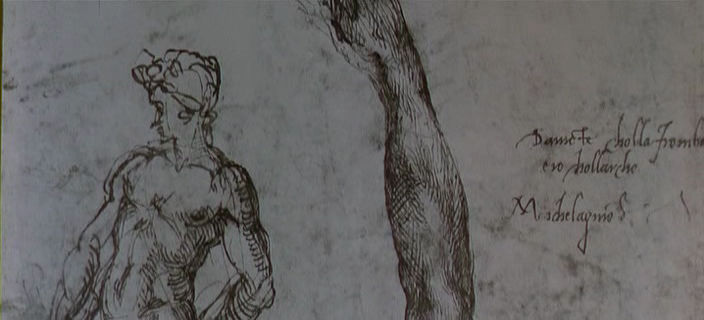

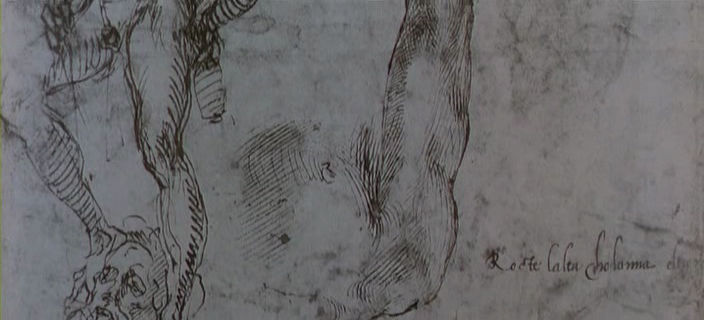

Titled The Artist Who Did Not Want To Paint, the documentary builds momentum and the sense of Michelangelo’s genius by starting small and ending big. After the establishing shots of the modern city surrounding St. Peter’s Basilica, sketches featuring Michelangelo’s handwriting appear on the screen as the camera pans across them dramatically. Following a series of nicely filmed sculptures, the documentary concludes by settling on two important religious sculptures: Moses and the Pieta, the former of which holds great thematic importance in the narrative that follows.

Figure 3: Starting small with rough sketches. Notice how the entire body of a man compares in size with the study of a single arm, suggesting the mathematical principles lurking behind the seemingly effortless composition.

Figure 4: By focusing on the knee of Moses, the film highlights Michelangelo’s apocryphal rage, the culminating blow of genius, the equivalent of Pete Townsend smashing his guitar after pleasing the masses, the ultimate Adamo mi fecit.

Arguably, the film adds this bloating documentary, replete with Jerry Goldsmith’s magisterial score, in order to match the novel’s scope and physical bulk and perhaps to compete with Stone’s research. But even if the film succeeds in this attempt to out-stone Stone, a gesture that places the film’s intermission in a narratively awkward place, the story portion of the film is hardly about Michelangelo the sculptor. Rather, the narrative focuses solely on his years of servitude painting the Sistine Chapel under the antagonistic eye of Julius II, and as Tashiro has suggested with reference to Griselda Pollock regarding the Van Gogh-themed Lust for Life (also adapted from a Stone novel), this kind of film uses the mise-en-scène to make its art-historical figure the subject of his own artwork.[3]

The Moses theme: Slavery, Exile, Divine Intervention

The documentary establishes Michelangelo as a sculptor of large works in marble and helps form the conscious desire that haunts the artist throughout the film as he contends with Julius II’s insistence that Michelangelo paint rather than sculpt. Thus, the documentary’s penultimate association of Michelangelo with Moses pays off when we first meet Charlton Heston, perhaps the actor most strongly associated with the Biblical figure Moses as a result of playing the bearded prophet with the stone tablets in The Ten Commandments (dir. Cecil B DeMille, 1956). Part of this effect may relate to what Boyum calls “resymbolization,” the sense that readers of a novel “will in some way already have made the movie.”[4] Only in this case, Heston, The Ten Commandments and perhaps nothing more than a passing familiarity with the Old Testament serve as the precedent materials with which viewers come to the film pre-projected in their heads.

Yet it is not just Moses and the famous list of prohibitions carved by God’s hand into tablets of stone, but the image of divine law itself that comes to us through Heston. In both versions of The Agony and the Ecstasy, marble represents not law but immensity of spirit and artistic intent (though as discussed below, stone also serves as weaponry in the film’s major action/disaster sequence). For this reason, although Rex Harris, who plays Julius II, appears in the initial encounter ensconced in royal colors atop a royal horse, the simply clad Michelangelo is both physically (in the mise-en-scène), symbolically and extra-diegetically positioned as the true giant in the face of the powers that be.

Figure 5: The American Moses supported by his beloved stone against the Pharaoh figure of Julius II.

Even without Charlton Heston to play his version of Michelangelo, Stone bases his characterization on the Moses archetype, not to mention on several other archetypes, including builder, inventor, seeker, thinker, dreamer, and artist driven to self-expression in the face of hardship and externally imposed constraint. And there is also the matter of being a changeling. For instance, Stone relates that Michelangelo was taken from his home and suckled by the stonecutter’s wife.[5] There is no tabula rasa in this passage; Michelangelo has stone in his blood through the symbolic totality of a partial adoption. In terms of Stone’s adaptation from the historical record, it is interesting to note that Michelangelo himself reportedly made such a claim to Giorgio Vasari:

The place was rich in a hard stone, which was constantly being worked by stonecutters, mostly born in the place, and the wife of one of these stonecutters was made nurse to Michael Angelo. Speaking of this once to Vasari, Michael Angelo said jestingly, ‘Giorgio, if I have anything of genius, it came to me from being born in the subtle air of your country of Arezzo, while from my nurse I got the chisel and hammer with which I make my figures.’[6]

Whether Michelangelo ever made such a statement or not, this initial bit of mythology is but the novel’s first scene of exile and adoption. Again and again, Michelangelo falls into the servitude and slavery of rich patrons and royalty, acting in each case as an interpreter of God via stone in an attempt to be free to pursue his love affair with sculpting. And what is the nature of this pursuit? For Stone’s Michelangelo, sculpting is always bound with space: “Time … Everybody wants me to give them time. But time is as empty as space unless I can fill it with figures.”[7]

And at the end of the tale, to close on the Moses theme in the novel, Stone keeps his Michelangelo out of Canaan itself, represented by the Basilica, allowing the artist access only in a deathbed dream as he heads toward the eternal light of heaven. Stone renders the imagery with Michelangelo’s desire to fill heaven perpetually with marble figures from the conjunction of his hand with the chisel and hammer in an ultimate union with God. That Michelangelo is kept from the object and practice of his desire so many times and in so many ways throughout the novel is part of his archetypal structure. His is the classical Oedipal ego, not in the Freudian sense (though one could look back to the stonecutter’s breast), but in terms of hamartia. Michelangelo is forever the cause of his own problems. His art is the poison that cures as well as the cure that poisons as Michelangelo is constantly “goaded”[8] into taking commissions he doesn’t really want. This motif of the hero engaged in jobs he’d rather not do was selected by the filmmakers precisely because it connects so closely with the pre-established assemblage of Charlton Heston and the reluctant Moses.

Creation, Destruction and Genre

Following a gradually escalating series of artistic entrapments, Michelangelo competes with Leonardo out of pride and self-contradiction. The tragedy in the novel is precisely Michelangelo’s inability to align his life with one of his many interrelated dictums that would place him as a divine interpreter of the Bible and its many figures. As Stone has Michelangelo say, “I believe God loves independence more than He does servility.”[9] Yet Michelangelo’s actions directly land him under Julius II’s equally grand ego and the command to paint the Sistine Chapel and “establish” Julius’ “historical position”[10] or go to jail. Stone quickly gives Michelangelo the first of numerous moments of self-revelation in which Michelangelo recognizes his situation as a direct consequence of battling with Leonardo[11] and then resolves himself to the work with the spirited decision to “get that ceiling splashed with paint.”[12] In terms of adaptation, this line from Stone’s novel sounds like the kind of Americanism Charlton Heston might spout, which makes one wonder why screenwriter Philip Dunne eluded it in his characterization of Michelangelo for the cinema.

Despite the endless despair in which Michelangelo knows “himself to be a victim of his own character,”[13] much of the scale of the painting is not so much connected with the Biblically inspired desire to “get a teeming humanity upon the ceiling,”[14] but bickering with Julius II over funding the project and bringing himself into alignment with God’s will. “Teeming” is a curious word in this context, one that English speakers normally reserve for wild game. Humans may spring from God’s will, but Michelangelo’s training in human anatomy—a long and grim passage Stone might have plucked directly from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein—keeps the mass of humanity locked within the rubric of animalism.

Curiously, Stone has Michelangelo practice a kind of internal parthogenesis as he paints. It begins with a Dionysian association of Michelangelo with Noah’s drunkenness, followed by searching for ways to “displace space” in painting without using the three dimensions of sculpture. Michelangelo decides upon being an “artistic womb,” self-hypnotically suggesting that “he himself was God the mother … inseminated each night by his own creative fertility.”[15] Soon, Michelangelo escalates himself to the status of God himself, “praying to himself” as he paints the Sistine Chapel ceiling.[16] True to the form of the Biblical God, Michelangelo punishes his humanity by placing himself in the context of Adam and Eve, resolving in the future to learn from his rash competition with Leonardo (a symbolic bite from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil) and from that moment forward to take “temptation in calm accepting strength rather than weak stupidity.”[17] But a full self-revelation never comes because part of Stone’s moral argument in the novel is that Michelangelo’s achievements in both sculpture and painting are intimately connected to his immense stubbornness as developed in the logic of the fiction.

The film does not and perhaps cannot take this psychologically torturous tack if it wants to deliver the requirements of a hero that supports the American status quo (many a critic would say that a film cannot support the psychological depth of a novel, but such positions represent prurient ignorance of the power of film). Thus, Philip Dunne’s script, credited in the film’s title sequence as “screen story and screenplay,” follows, not Stone’s novel, but Classical Hollywood movie structure (or narrative sculpture) of the Joseph Campbell kind that Star Wars later made so famous: Julius II, as a human being, provides the first call to adventure, producing a dilemma that offers no satisfactory solution for Michelangelo to pursue. In response to the dilemma (to paint against his will for a tyrant or risk a life void of art altogether), Michelangelo refuses the call in a rage, destroying his self-inspired work on the Sistine Chapel. The destruction is easily achieved in a single act of violence; up to this point in the film, Michelangelo has produced little more than sketches and a single cartoon. Working solely from the dictates of Julius II’s human command here on earth, the output is small …

Figure 6: A Robin Red Breast in a Cage, Puts all Heaven in a Rage.

… until during Michelangelo’s self-imposed exile in what screenwriters and screenwriting guru John Truby calls “the visit to the underworld.”[18] Then Michelangelo sees the consequences of his decision not to paint the chapel: a life of servitude in a rock quarry where he produces stones for other sculptors to enjoy. In the novel, the stone quarry serves as a metaphor for sculpture itself: “Once marble is out of its quarry, it is no longer a mountain, it is a river. It can flow, change its course. That’s what I’m doing, helping this marble river change its bed.”[19] In the film, the quarry becomes an opportunity for a standard action sequence as Michelangelo’s co-workers in the quarry help him evade Julius II’s troops by violently unleashing a large slab of marble that slides into the path of the mounted soldiers. In terms of fidelity with the novel, there is no basis for comparison with this scene. Rather, the film contends with the magnitude of the source material by slotting it into prefabricated genre conventions.

Figure 7: The stone quarry serves as an excuse for an action scene that smacks of a crumbling mountain in a film from the disaster genre.

After languishing in a cave that prefigures his imprisonment in the chapel itself, God proffers Michelangelo the second call to adventure through the sublime inspiration of divine nature, which essentially dwarfs both Michelangelo’s body and will until he accepts this second beckoning. We shouldn’t miss the parallel here with Moses up on the mountain conversing with God in The Ten Commandments, in which both Heston characters ultimately submit to the will from on high by sharing the same lofty space with an amorphous divinity. Whereas the novel brings us Michelangelo’s self-revelations in spats of internal dialogue as he paints the Sistine Chapel, the film externalizes the transformation in a single moment with the kind of natural tableaux popular in films of the era, made possible by the 2.20 aspect ratio used for 70mm standard film. (Todd-AO film stock, a popular brand during the 1950s and 1960s, was used, and thus the look of The Agony and the Ecstasy resonates with Todd-AO’s trademark tone and dimensionality).

Figure 8: Like many a prophet before divine revelation, Michelangelo languishes in a cave.

Figure 9: Divinity calls Michelangelo to adventure.

Whereas the novel dabbles in matters of historical consequence by way of situating Michelangelo in the midst of a variety of political conflicts, the film grandiosely exploits this muted trend in Stone’s prose by eliding any actual facts in favor of inserting elements of the Gladiator genre. Amidst the numerous fields of soldierly processions and battle scenes led by Julius II, it is little surprise when Michelangelo emerges from his self-imposed exile as a kind of rogue solider who returns to save the botched plans of his well-meaning but ultimately arrogant and ignorant commander, Julius II. In terms of this scene’s musical dimensionality and its relationship to gladiator films and genre films structured around literal and figurative battle, Schubert observes that the score itself embeds historical scale along with Hollywood convention. The music in this scene cites Clement Janequin’s 16th century arrangement “La Guerre,” which suggests that the film’s main composer, Alex North “knew the significance of early music well enough to grasp its appropriateness for particular film situations.”[20]

Figure 10: The rogue general lays out his battle plan for attacking the Sistine Chapel as adapted elements of Janequin’s “La Guerre” flavors Alex North’s score.

Scales of Character in the Church

It is on Julius II’s battlefield, surrounded by soldiers and the implied expanses of war that Michelangelo lays out the extraordinarily detailed draft for the Sistine Chapel ceiling that his exile and encounter with God has inspired. The theme of war is then sublimated into the battle between Michelangelo and Julius II as Julius and his gang of monks and priests continually press Michelangelo for progress on the project. The film’s sightlines flow in vertiginous scenes of confrontation between Michelangelo’s lofty position as a symbolic God of art and the earth bound servants of the Bible and their human-made creeds. But notice how both parties are entrapped by the wooden cage of the scaffolding, suggesting that despite his transcendence, Michelangelo must remain as theatrically human as his enemies in the church.

Figure 11: High or low, all parties are visually entrapped by the scaffolding.

In the novel, the relationship between Michelangelo and Julius II is simply a matter of fact. Julius survives only a few months after the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is complete, leaving Michelangelo to contend with the “space-famine”[21] he had suffered throughout the painting process in the absence of sculpture, cured by pure integration with the stone he adores: “Carving the Moses, mounds of white dust caked in his nostrils like tranquility settling into the marrow of his bones.”[22]

The film, on the other hand, closes on a note of antagonism in keeping with its fusion of the novel with gladiatorial cinema. The final battle between Michelangelo and Julius II plays with scale, returning us to the opening motif. Even without the stone to bolster him, Michelangelo is positioned higher and taller in the frame next to the ailing Julius II. But although Michelangelo is in the higher position as both a physical body, an artist and a dignified human being, Julius takes the upper hand by demanding that Michelangelo paint The Last Judgment (which goes unnamed by the film) on the wall behind the altar. Not in spite of, but despite the utter historical inaccuracy of Julius II’s command, something Stone cleaves to more completely in the novel, the film bends the facts in favor of the Classical Hollywood denouement, fleshed out with a surprise ending that leaves Michelangelo on his knees. But despite Michelangelo’s defeat on the level of plot, emphasized by the long shot of his small body surrounded by the walls of the huge chapel, he symbolically leaves the film much more dignified than his enemy. We end with Michelangelo as immortal as God, so long as the artifacts savored by the camera of the opening documentary happen to survive, even as modern parking lots and automobiles encroach upon the Basilica. In this atmosphere, Michelangelo is the modest American Christ-hero who stays the course in the face of prosecution, the artist who turns the other brush to paint heaven after an earthly smack on the cheek.

Figure 12: Julius leaves Michelangelo on his knees in the immense space of the chapel, dwarfed by the architecture, but much more dignified as its decorator than Julius as its villainous CEO.

In conclusion, the film selects from the novel only those elements that can be readily snapped into the reigning film conventions of the time. Although the temptation to see the film’s use of space as a compensation for the novel’s numerous reflections on the nature of both physical and spiritual size lingers, particularly in the context of the film’s opening documentary, Carol Reed’s The Agony and the Ecstasy must ultimately be seen in the context of other epic films of the era beyond The Ten Commandments. The fetish for constructing huge spaces and architecture like the Sistine Chapel is a reigning characteristic of similar historical-novel adaptations like Ben Hur (dir. William Wyler, 1959) and Spartacus (dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1960). Although the scale of the raw materials and artworks certainly connect with Michelangelo at the biographical and art historical level, as we have seen, they are played for effect within specific genres, in connection with other films and narrative archetypes such as Moses, and for visual-symbolic effect. That scale plays into this arrangement reflects the monumental task of fixing a massive personality between the pages of a book or into the body of an actor, two realms of imaginative substance far different than the bulky medium of the real Michelangelo’s beloved stone.

Acknowledgements: Sincerest thanks to Henry Keazor and Nils Peiler at the University of Saarland for their thoughts and knowledge regarding both the novel and the film of Agony and the Ecstasy. My deepest gratitude goes as well to the DFG’s Mercator-Gastprofessor grant ((Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft). Their support facilitated the creation of this article.

Notes

[1] Irving Stone, The Agony and the Ecstasy, (New York: Signet, 1961, 1987), 228.

[2]Ibid., 530.

[3]Charles Tashiro, “When History Films (Try To) Become Paintings,” Cinema Journal, Vol. 35, No. 3. Spring (1996): 28.

[4]Joyce Gould Boyum, Double Exposure: Fiction into Film, (New York: Universe Books, 1985), 43.

[5]Stone, Agony and the Ecstasy, 17.

[6]Giorgio Vasari, “Lives of the Artists,” Fordham University, http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/vasari/vasari26.htm

[7]Stone, Agony and the Ecstasy, 305.

[8]Ibid., 410.

[9]Ibid., 471.

[10]Ibid., 500.

[11]Ibid., 501.

[12]Ibid., 509.

[13]Ibid., 526.

[14]Ibid., 518.

[15]Ibid., 530.

[16]Ibid., 531.

[17]Ibid., 533.

[18]John Truby, The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Storyteller, (New York: Faber & Faber, 2008), 131.

[19]Stone, Agony and the Ecstasy, 400.

[20]Linda Katherine Schubert, Soundtracking the Past: Early Music and its Representations in Selected History Films, (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1994), 244.

[21]Stone, The Agony and the Ecstasy, 554.

[22]Ibid., 554.

Anthony Metivier is currently developing www.scriptcastle.com, a website devoted to film literacy, while writing a book based on his recent research into the aesthetic, philosophical and commercial relationships between novels, films and paintings that fall under the general rubric of Adaptation Studies.

Media Fields Journal

Media Fields Journal