Re-presencing, Re-containing, and Re-materializing Music

Friday, April 30, 2021 at 4:48PM

Friday, April 30, 2021 at 4:48PM Jörgen Rahm-Skågeby

[ PDF Version ]

Introduction: Music as Signal Manipulation

In certain ways, music is now immaterial(ized). A range of music streaming services distribute signals to us—across space and time—decoded as music by multi-functional devices, such as phones, tablets, laptops, TVs, and smart speakers. Music is no longer bound to certain inscriptions and formats. As such, the question of what these music streaming services actually do has interested several scholars.[1] The underpinning reason being that these services are not just sending pure music to our ears—as we listen to streaming music, there is a concurrent measurement, surveillance, manipulation, and commercialization of the data traffic that now constitutes the core of music mediation. A form of signal logistics—aimed not only at “the timely provision of the right information to the needing actors—human or machine”, but also at optimizing much wider systems of control.[2] At the same time, older music formats are experiencing a revival—a “re-presencing,” “re-containing” or “re-materialization” if you will—making use of physical formats, such as audio cassettes, and vinyl records. This tension between “music in the cloud” and music inscribed in a physical container may at first glance seem straightforward, but as several researchers have shown the distinctions are far from clear.[3] This paper will add to this ongoing discussion by looking to the concepts of data logistics, “re-presencing,” and material ecology.

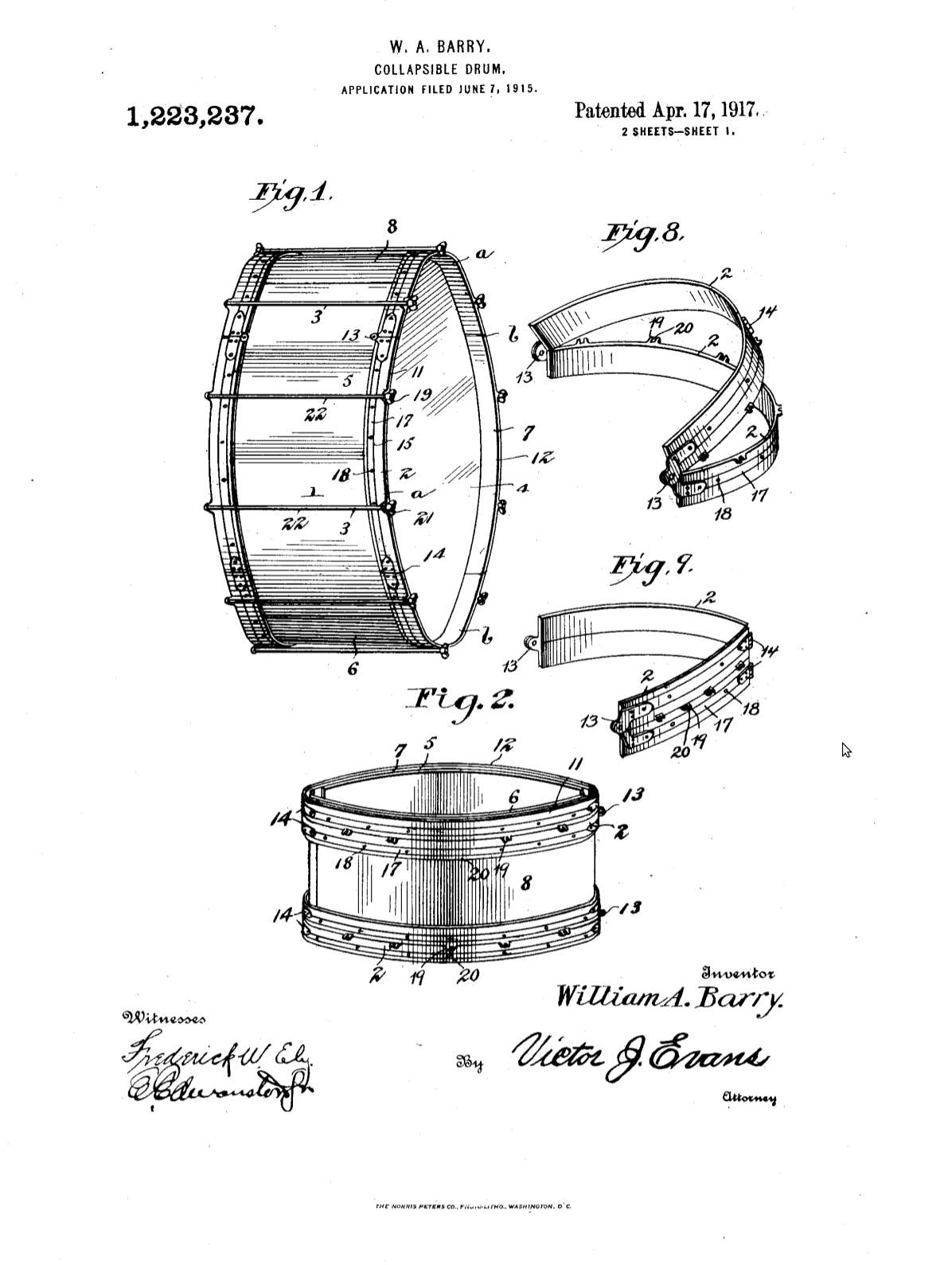

To begin with, music was (of course) never a question of just transmitting a pure signal—a certain amount of manipulation has always been present in music. That is, music was always mediated and always a product of technology, which means that, as a starting point, we could take up conceptualizing musical instruments as media. Media, in the sense that they are conveying and manipulating a signal, in order to change the sound patterns; the pitch, the tone, the sustain, and so on. A simple drum of the kind depicted below produces sound through vibrations across a membrane stretched over a hollow cylinder body. It has been designed like this so that the original signal—the vibrations that are generated in the intra-action with a drum stick or a hand—can be amplified, and present new possibilities for musical and rhythmical manipulation.

Figure 1. Drum patent

Other instruments work in other ways, of course—and to be sure, this is not just for specially dedicated musical instruments such as drums, violins, or trumpets; we can use any object as a musical medium, as long as the intention and context are about making music. But the point being made here is that music was always mediated and was always a technological product in some sense. And that there are aspects of this construction—specifically, design and materiality—that literally play into how the signal is being communicated and distributed to its intended receivers.

Early Algorithmic and Distributed Music

Most instruments take certain skill, talent, and acquiring of bodily techniques to be played with finesse and elegance, which has meant that throughout history there has been a certain human fascination with constructing self-playing instruments. In the context of this paper, we can refer to them as instruments where the original signal does not require a human hand for its generation—to eliminate the musician in some sense. And this is where we can make a first interesting connection to the case of music streaming in the present day, when we deal not only with self-playing machines, but also self-listening machines—that is, computer programs or bots that have been programmed to “listen” to music in order to learn musical patterns. Or indeed, as we have seen in the news recently, as a way to perform music stream manipulation—accumulating stream counts —so that artists seem more popular than they really are.[4]

But let us dwell on self-playing instruments for a little longer. In order to be realized, self-playing instruments required new forms of storage and new forms of music recall. Previously, the storage medium was the notation (that is sheet music or music inscribed as notes) and the musician, who, using their talent and skill, interpreted the notation and performed the music together with their instrument. The interesting thing here is, on the one hand, how music now required new storage formats—in the beginning punch cards, cylinders, and discs of different kinds— and on the other hand, how this made the instrument, or medium, programmable in some sense. Now, not only could one adjust beforehand how the instrument sounded and manipulated audio signals in themselves, but one could also inscribe which notes should be played in what order and store these sequences and combinations for later autonomous performances.

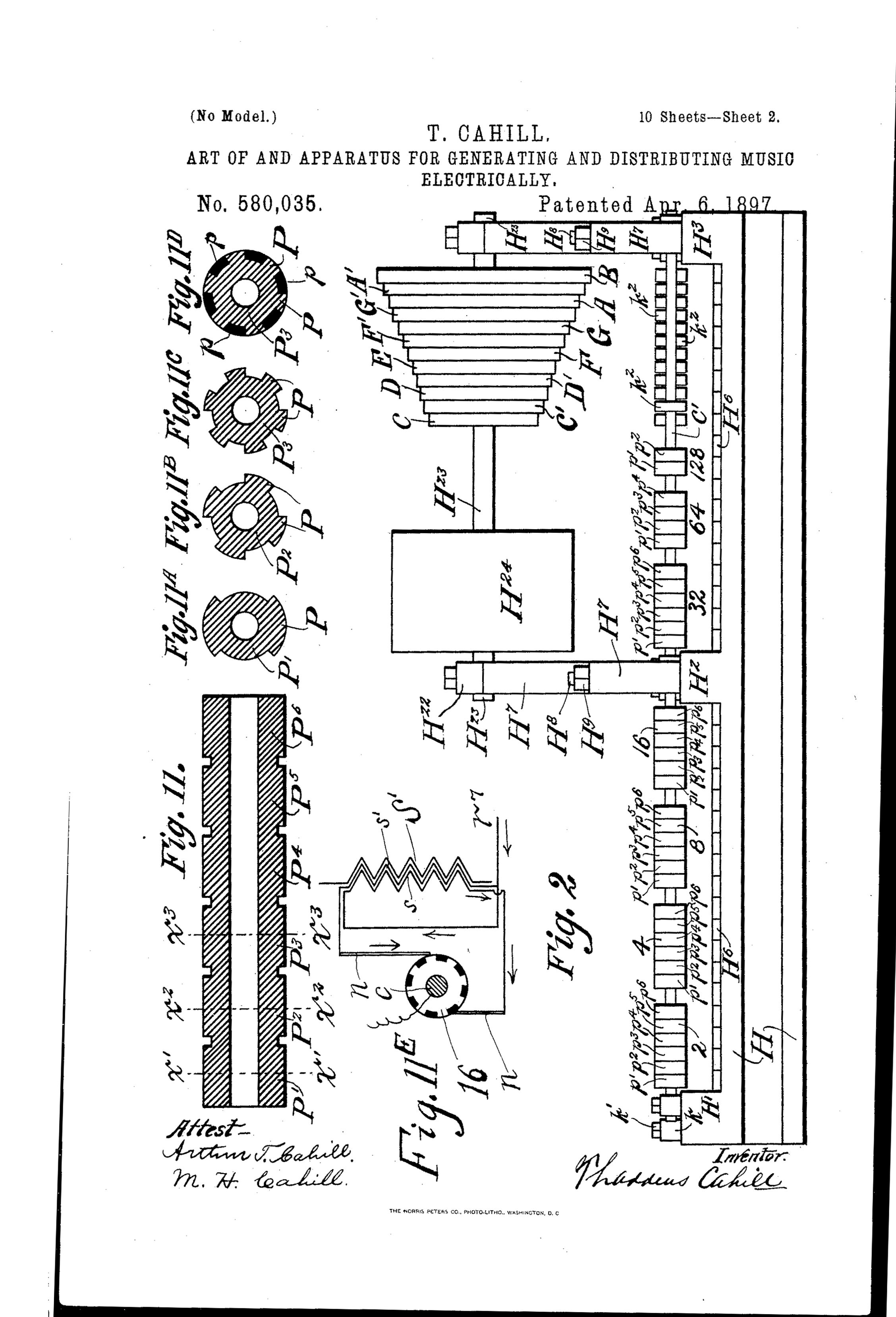

Figure 2. Telharmonium

It is also interesting to notice that there have been historical attempts and experiments in communicating music at a distance—both stored music and live music. Of course, the radio is an obvious example, but there have also been other ambitions to this effect. A first swoop can be made in 1895, when Thaddeus Cahill submitted a patent for the Telharmonium—"The Art of and Apparatus for Generating and Distributing Music Electrically."[5] This machine, regarded by many as the first electronic instrument, not only incorporated a method for creating synthetic sounds electromagnetically, but also showed an ambition to distribute these sounds over the telephone wires in the US.[6]

What Cahill wanted to achieve was partly a perfect instrument. He found that most of the instruments used at the time—such as pianos, pipe organs, string and wind instruments—had individual weaknesses, which the Telharmonium was able to overcome, thereby making these other instruments superfluous. So, this was an instrument that, through science and mechanical control, would be able to generate perfect tones. This idea of converging other media into one, and creating a hypermedium that makes other actors, formats, and technologies obsolete is something that we can identify as a recurring desire, or topoi, over time. The other interesting aspect of this machine was how this electromechanical music could also be distributed across the telephone grid, and into homes, hotels, and public places to make use of the existing communication infrastructure as a way to distribute music.

Half a century later, during the 1940s, there was another music platform, also in the US—in Pittsburgh to be exact—called the Telephone Music Service. It was made up of several jukeboxes connected to the telephone grid and placed in various bars and cafés.[7] You could put a coin in the machine, pick up the receiver, ask the operator/musical host for a particular song that you liked, and before you knew it, your requested song would emerge from the speakers of the jukebox. It was an on-demand music streaming service.

There are of course many other examples such as these, but the important thing to note is that since then, we have had lots of combinations of different inscriptions techniques, storage formats, and media technologies with their own specificities—wax cylinders, shellac records, vinyl records, reel-to-reel tape recorders, cassette tapes, minidiscs, CDs, and so on. New storage formats in combination with new recording and playback technologies also gave rise to new bodily techniques and situations of consumption: the family gathered around the radio or TV; dancing in a nightclub; headphones for more shielded, but perhaps also more narcissistic listening; a boombox out in the street; a traveling gramophone on the beach or on the picnic table; a listening booth in a record store; a sound system in a back yard… just to name a few of the situations, technologies, techniques, and formats for which music has been a central part of a larger cultural practice.

Enter Data Logistics

In a slightly more modern age, when distributed music became a cultural industry and a market—that is, when it became something that could generate monetary profit—a will to logistically monitor and manipulate consumption of music emerged. Sales figures, music charts, fan clubs, radio, and TV shows with or without audience response technologies, the possibilities to persuade or even bribe radio disc jockeys to play certain songs and so on, became tools in new kinds of music logistics that turned music into business for real. But with the advent of the Internet, and this is a terrible cliché of course, but still, with the Internet, such logistics reached new levels of efficiency.

Seeing how music for many now consists of quantified data transmitted over the internet—the possibilities to logistically measure, monitor, manipulate, and commercialize music is unsurpassed. Sales figures and charts are still important, but now the actual signals themselves—the music itself—can be traced with much higher efficiency and accuracy. What we are seeing is a new form of encoding of culture in combination with spatiotemporal mediation. The phenomenon of streaming music is a new form of infrastructure for cultural consumption, where new centers and new margins emerge. The feed-forward loops that are integrated into the streaming of music, also try to predict, and manipulate music consumption, by recommending similar artists, organizing music into playlists, and detecting and delineating between legal and illegal use of music; just to mention some of the more visible mechanisms of this spatiotemporal infrastructure.[8]

Re-presencing, Re-containing, and Re-materializing Music

Media reports have for some time claimed that, for example, cassette tapes and vinyl records are gaining in popularity.[9] Is this a way to refute the data logistics of streaming music? One way to phrase it, leaning on theorist Sobchak, is to see it as a way of re-presencing bygone music containers.[10] Sobchack proposes that re-presencing can not only bring forth (in the Heideggerian sense), but also make present specific operative practices, and that re-contained music can generate a real, almost existential, encounter with (previously) obsolete, forgotten, or outdated music containers and their epistemological and sensual specificities. Additionally, re-presencing, or re-containing, also brings a perplexing disruption to the temporal flow of media development, “challenging and changing the accepted order of things […] overturning the premises (and comprehension) of established media hierarchies and media histories."[11] Here presence makes its mark as an unexpected effect emerging from introducing something “archaic” or “offbeat” in the present—something which can, incidentally, also appear as strikingly familiar, as well as physically simple(r).

While this process of re-containing music—of moving it across different container technologies—can give the impression that there is a process of de-materialization and re-materialization going on, it is also important to remember, echoing the introduction to this paper, that music was always a technological product grounded in material practices. Even today when music can appear more immaterial than ever, described as streams of intangible zeroes and ones, there is a fundamental layer of materiality. Demonstrated by a recent ecological turn in media studies, there is an interest in “excavating” a very concrete materiality of technology that problematizes re-presencing and re-containing.[12] A focus on the raw materials used in the production of media technologies (including, as we shall see, re-presenced music containers) highlights a distinct connection to geology and an exploitation of natural, as well as human, resources.

That is to say, that both in production and in the phase of disposal, inscriptions of music have an ecological impact. Kyle Devine paints a revealing picture of three phases of the materiality of modern music in his book Disposed.[13] Beginning with the notoriously fragile shellac records, moving on to polyvinyl chloride, polycarbonate, and metal oxide formats, and finally arriving at digitized music formats, he shows how there has always been a distinct material connection to both human bodies, geological exploitation, and capitalist culture. Arguably, this presents a dilemma, paradox, or even aporia, in that digitized music relies “on infrastructures of data storage, processing and transmission that have potentially higher greenhouse gas emissions than the petrochemical plastics used in the production of more obviously physical formats such as LPs – to stream music is to burn coal, uranium and gas."[14] Devine goes on to argue that while individual streams may be negligible in terms of environmental impact, the expectations from listeners to have immediate access to infinite volumes of music have also created aggregate effects that far surpass the “emissions profile at the height of vinyl, cassettes or CDs.”[15]

So, both streaming music and renewed interest in obsolete formats present difficulties. Perhaps new physical eco-formats, or more environment-friendly re-presenced ones, can be a conciliation for the future?[16]

Notes

[1] Sofia Johansson et al., eds., Streaming Music: Practices, Media, Cultures (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018); Maria Eriksson et al., Spotify Teardown: Inside the Black Box of Streaming Music (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019); Arnt Maasø and Anja Nylund Hagen, "Metrics and Decision-Making in Music Streaming," Popular Communication 18, no. 1 (2020): 18-31.

[2]. Haftor, M. Kajtazi, and A. Mirijamdotter, "A Review of Information Logistics Research Publications," in Business Information Systems Workshops. BIS 2011. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, vol 97, ed. Abramowicz W., Maciaszek L., and Węcel K. (Heidelberg: Springer, 2011), 254.

[3] Michael Palm, "Keeping What Real? Vinyl Records and the Future of Independent Culture," Convergence 25, no. 4 (2019): 643-656; Paul. E. Winters, Vinyl Records and Analog Culture in the Digital Age: Pressing Matters (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2016); Dominik Bartmanski and Ian Woodward, "The Vinyl: The Analogue Medium in the Age of Digital Reproduction," Journal of Consumer Culture 15, no. 1 (2013): 3-27.

[4] Bruce Houghton, "4 Ways Artists, Labels Manipulate Spotify, Apple Streams and How It Hurts Everyone," Hypebot, 2019, http://www.hypebot.com/hypebot/2019/08/4-ways-artists-labels-manipulate-streaming-and-how-it-hurts-everyone.html; Elias Leight, "Fake Streams Could Be Costing Artists $300 Million a Year," Rolling Stone, 18 June 2019, http://www.rollingstone.com/pro/features/fake-streams-indie-labels-spotify-tidal-846641/.

[5] Reynold Weidenaar, The Telharmonium: A History of the First Music Synthesizer, 1893-1918 (New York, USA: New York University, 1988).

[6] Morten Riis, Machine Music: A Media Archaeological Excavation (Aarhus, DK: Aarhus University Press, 2016).

[7] Zack Furness, "Did You Know Music Streaming Has Roots in Pittsburgh?," Pittsburg Magazine, 17 October 2019, http://www.pittsburghmagazine.com/did-you-know-music-streaming-has-roots-in-pittsburgh/.

[8] Maria Eriksson, "Online Music Distribution and the Unpredictability of Software Logistics" (PhD dissertation, Umeå university, 2019).

[9] Kevin EG Perry, "Yep, Cassettes Are Now the New Vinyl," GQ, 18 May 2020, http://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/culture/article/cassette-tapes-revival; Alex Ledsom, "The Walkman and Cassette Tapes Are Making a Comeback," Forbes, 19 January 2020, http://www.forbes.com/sites/alexledsom/2020/01/19/the-walkman-and-cassette-tapes-are-making-a-comeback/; Ben Sisario, "The Vinyl? It’s Pricey. The Sound? Otherworldly." New York Times, 28 April 2020, http://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/28/arts/music/electric-recording-co-vinyl.html.

[10] Vivian Sobchack, "Afterword: Media Archaeology and Re-Presencing the Past," in Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications, ed. Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 323-334.

[11] Ibid., 324.

[12] Jussi Parikka, "Deep Times and Media Mines: A Descent into Ecological Materiality of Technology," in General Ecology: The New Ecological Paradigm (pp. 169-192), ed. Erich Hörl (London: Bloomsbury, 2017); Sy Taffel, "Technofossils of the Anthropocene: Media, Geology, and Plastics," Cultural Politics 12, no. 3 (2016): 355-375; Sy Taffel, Digital Media Ecologies: Entanglements of Content, Code and Hardware (London: Bloomsbury, 2019).

[13] Kyle Devine, Decomposed: The Political Ecology of Music(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019).

[14] Kyle Devine, "Nightmares on Wax: The Environmental Impact of the Vinyl Revival," The Guardian, 28 January 2020, http://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/jan/28/vinyl-record-revival-environmental-impact-music-industry-streaming.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Amy Fielding, "Can Our Vinyl Obsession Ever Be Environmentally Friendly?," DJ Mag, 31 January 2020, http://djmag.com/longreads/can-our-vinyl-obsession-ever-be-environmentally-friendly.

Jörgen Rahm-Skågeby is an associate professor at the Department of Media Studies at Stockholm University, Sweden. His research involves media archaeology as well as (humanistic) human-computer interaction and human-machine communication.

Reader Comments