Documentary Space, Place, and Landscape

by Elizabeth Cowie

A landscape is both a space and a view, within which places are differentiated as particular and specifically identified lived spaces. Mobile phones and the internet audio-visually connect people across the formal and informal boundaries of space in a lived embodied experience. In film, however, the world seen and recorded as sounds and moving images is a landscape and place over there, presented for our view here, in another space, such that we can only bodily engage the seen and heard as listeners and viewers and not as interlocutors. There are three ways of experiencing landscape that I want to distinguish here. The first is landscape as pictorial, as an audio-visual performance of place and space that, with its occupants, is visible evidence. Drawing on Gilles Deleuze’s account, we might call this a documentary “movement-image” cinema. Secondly, we may experience documentary's ability to show place and space as immanent, and as “time-image” in a freeing of depicted time from the temporal causality of cinematic representation as a chronological succession from then to now.[i] The “direct time-image,” Deleuze writes, “always gives us access to that Proustian dimension where people and things occupy a place in time which is incommensurable with the one they have in space.”[ii] It is a work of memory (and mourning) of a before and an after “as they coexist with the image, as they are inseparable from the image.”[iii] Deleuze sees this as a process of “becoming,” not only within the documentary’s images and sounds but also within the spectator in her apprehension of an incommensurability of the referenced and its temporality, and thus of an undecidability.[iv]

Documentary film, in its presentation of scenes of landscape and space, thereby also organizes these to produce a place of view for the spectator as a cognitive and emotional experience, so that we participate both as observers and as engaged in identifying, and this constitutes a third way in which we may encounter landscape. For documentary, in its imaging of space and its remembering in people’s recorded stories, can also give image and voice to the experience of place as home, as heimlich. The walls and borders that separate and define place and home may, however, become a containment that, if breached, might signify freedom for those ‘within,’ but also a threat from, or to, those “outside.” Here might arise a certain uncanny sense—the unheimlich—as Sigmund Freud termed this.[v] It is a response to what is apprehended and thence it demands a certain “translation” as thought.

In this essay I explore ways in which we may encounter in documentary the process of immanent becoming arising in the time image, a process that is distinct from the spectator’s coming to know the facts. The landscapes and places that I will be considering are firstly Palestine and Israel, in Kamal Aljafari’s Port of Memory (2009), and in two films by Hanna Musleh, I’m a Little Angel (2000), and Memory of the Cactus (2009); and secondly, California in James Benning’s El Valley Centro (2000).[vi] In each film the facts on the ground are also facts of ownership and its politics that determine living and being in these spaces.

Landscape is part of what defines and delineates the documentary participants individually as people, but also as part of a community or nation. But it is as well a space of action, for people live and are thereby made in this living through their embodied relation to landscape as a material world for work, home, and family within and beyond that landscape. Places, however, are name-holders, identifying a site of activity and experience that may be recorded on maps while also belonging to collective memory. The land, meanwhile, changes as a result of both natural forces and human intervention; geological and weather events change the landscape, throwing up new islands as a result of seismic activity, or submerging coasts and their towns and villages (as seen with devastating effects in Japan in 2011), while humans clear forests for agriculture, and channel water for irrigation. In each case there will be uncontrollable and unpredictable results. The land and its occupants are both friend—a source of food, shelter, friendship, and kin—and foe, seen in the dangerous, brutal, and unknown of untamed nature or the feared other.

Doreen Massey presents a powerful materialist view of landscape:

For me, places are articulations of “natural” and social relations, relations that are not fully contained within the place itself. So, first places are not closed or bounded—which, politically, lays the ground for critiques of exclusivity. Second, places are not “given”—they are always in open-ended process. They are in that sense “events.” Third, they and their identity will always be contested (we could almost talk aboutlocal-level struggles for hegemony).[vii]

How might documentary works engage us in such “events” of landscape and place, and in the contestations arising through the landscape’s imaging? The Palestinian landscape is familiar from its picturing as biblical, but now as a contested space, it is sundered and expropriated. Landscape and the places it contains have become a reference charged with affect.

Raja Shehadeh, a Palestinian lawyer living in Ramallah in the occupied West Bank, has written of his experience of his homeland:

Sometimes, when I am walking in the hills ... unselfconsciously enjoying the touch of the hard land under my feet, the smell of thyme and the hills and trees around me—I find myself looking at an olive tree, and as I am looking at it, it transforms itself before my eyes into a symbol of the samidin, of our struggle, ofour loss. And at that very moment, I am robbed of the tree; instead there is a hollow space into whichanger and pain flow. I have often been baffled by this—the way the tree-turned symbol is contrasted in my mind with the sight of red, newly turned soil, barbed wire, bulldozers tearing at the soft pastel hills—all the signs that a new Jewish settlement is in the making.[viii]

Here is a place whose landscape is different for each people, both as the now of material, bodily experience, and as recalled in memory as image-become-symbol. Palestinian documentary film is not only an engagement with the erasure Shehadeh refers to, but also an assertion against such erasure, in a kind of stating that can be summed up as: “here we are, living and being.” It enables a becoming seen and known in a “Palestinianess,” both in documentaries by 1948 Palestinians who are now Israeli citizens and by those in the West Bank and outside. Port of Memory (2009) presents Arab Israeli Kamal Aljafari’s home town Jaffa, now part of Tel Aviv, in which the conflict of erasure is realized in the materiality of the walls of decaying houses that were once Palestinian homes but whose owners cannot return, and in the problems his aunt and uncle, Fatweh and Salim (brother and sister), encounter in relation to their right to their home that has been family-owned for generations. Intercut are scenes from action adventure movies that used Jaffa as an exotic location—Kasabian (1974), Menachem Golan, The Delta Force (1986) with Chuck Norris. Now they provide documentary evidence of a living city gone except for the shards that we see remaining—the streets, the cemetery, the stones and walls of homes that reference the lives once lived there. In this essay film we encounter the image of Palestinian Arab living haunted by loss made palpable through its documenting of life. Fatweh makes floral bouquets, while caring for their mother, seen in the film clip that also shows her obsessive hand-washing after an uninvited Israeli caller enquires about whether the house is for sale.[ix] Fatweh and Salim perform themselves for the film’s larger story of Jaffa’s Palestinian past and Israeli present, together with semi-fictional scenes that introduce surreal elements, of men in a 1930s glassfronted café, and a man on a motor scooter shouting, and the closing shots of a new Israeli-built viewing point. These scenes are unexplained, unaccountable except through our reflection, thus they engage us as time images.

Shards of life lived

Decaying houses

Salim walking through the streets of Jaffa's decaying houses

Salim, Fatweh and their mother

Fatweh arranging a bouquet for a wedding

The café

The newly-built picturesque viewing point in Jaffa

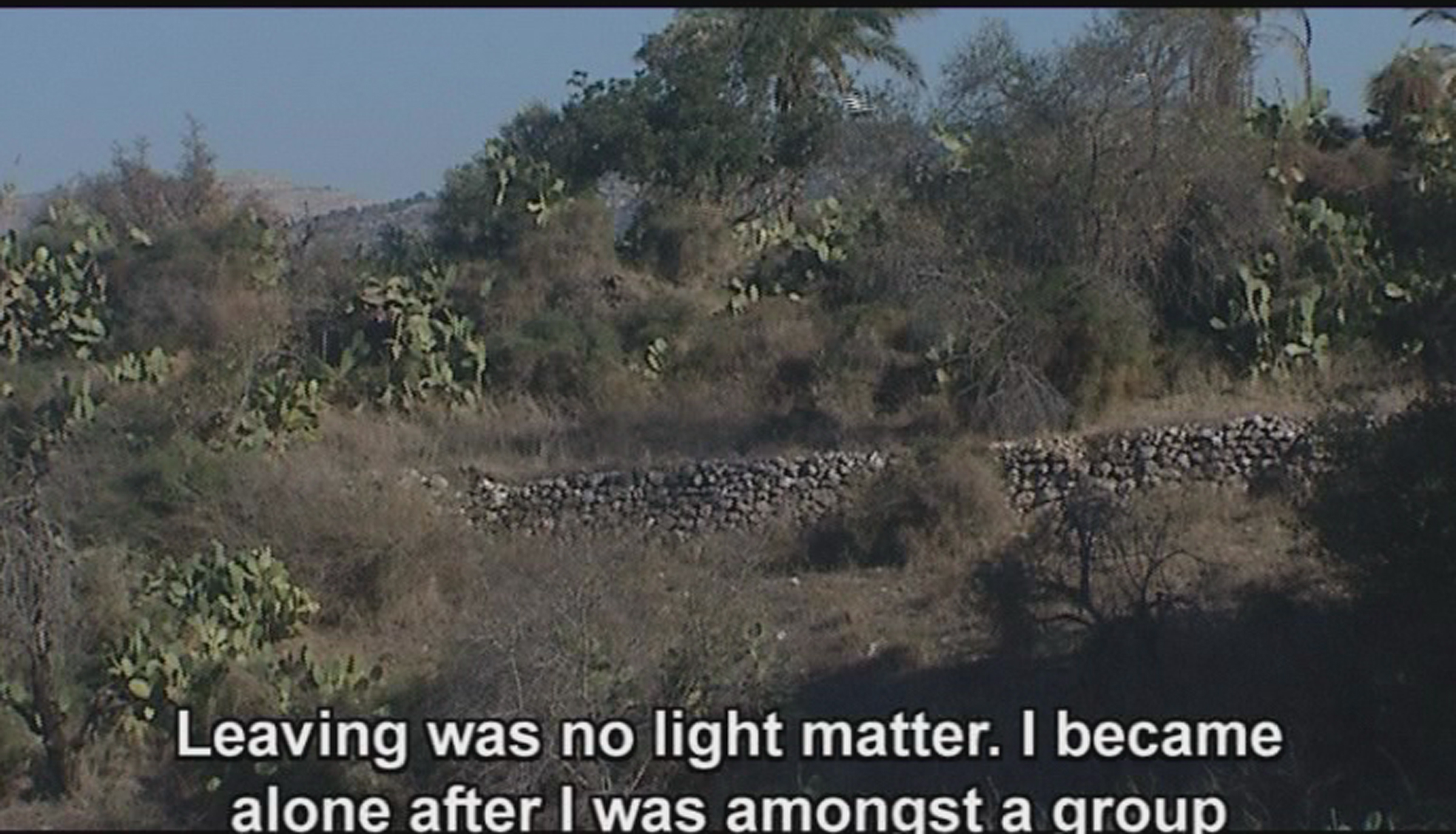

In documentaries of the occupied West Bank, erasure is imaged in the wall that sunders families and communities, in the spaces filled with blackened tree stumps of former olive groves, now missing to ensure “security,” and in the cactus that still grows, demarcating cultivated land whose owners have been expelled.

This materiality of the landscape becomes figural, such that Shehadeh writes, “[w]hen you are exiled from your land … you begin, like a pornographer, to think about it in symbols. You articulate your love for your land in its absence, and in the process transform it into something else.’’[x] The symbolization reifies and, in this process, something is lost, namely, a potential for thinking differently. But in these Palestinian films we encounter a documenting of the now of everyday living that unfixes such reification. This is a storytelling of vignettes, moments, digressions, stories within stories, and postponed endings. These are stories of interaction, of something happening, in a documenting of a being and doing now, while awaiting a future yet to be known, and at the same time asserting a past history to be remembered through these images and sounds. Through this there arises the accenting of these films, to draw on Hamid Naficy’s term, namely a specific tone of a past—the Nakba or catastrophe—as a continuing present, insofar as the conflict does not allow Palestinians to imagine themselves in a determinate future of place and landscape they can call their own, namely a state.[xi]

In Hanna Musleh’s I’m a Little Angel (2000), we follow the children of families, both Muslim and Christian, in the area of Bethlehem affected by the 2000 Israeli armed forces attacks and occupation.[xii] One small boy, Nicola, suffered the loss of an arm when he was hit by a shell when walking to church with his mother. His kite, seen flying high in the sky, brings delighted shrieks from Nicola as he plays on the family terrace from which the town and its surrounding hills are visible in the distance. But the contrast between the freedom of the kite in this unlimited vista and his reduced capacity is palpable as he struggles to control it with his remaining hand. The containment of both Nicola and his community is figured in opposition to a possible freedom. What is also required of us is to think not of freedom from the constraints of disability, but of freedom with disability, in a future to be made after. The constraints introduced upon the landscape by the occupation, however, make the future of such living indeterminate and uncertain. Here is the “cinema of the lived,”[xiii] of multiple times of past and present, of possible and imagined future time, and the actualized present, each of which is encountered in the movement in a singular space of Nicola and his kite.

Nicola and his kite, with his mother’s voice-over, in I’m a Little Angel (Hanna Musleh, 2000)

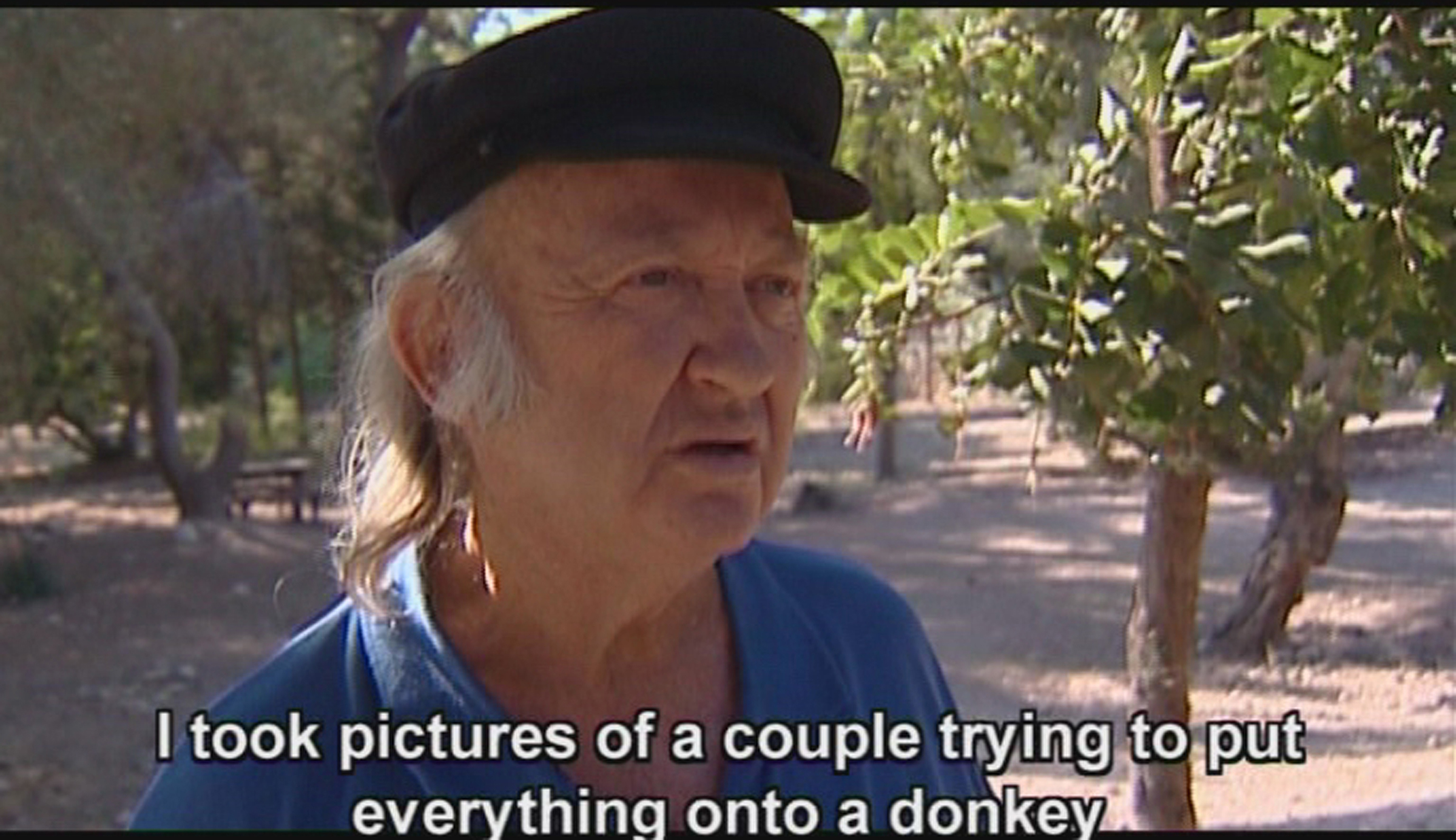

The documentary time-image is an anthropology of place and space insofar as our dwelling in place and space involves our dwelling with both a landscape and fellow people, and thus a community. Martin Heidegger writes that, “[t]he relationship between man and space is none other than dwelling, strictly thought and spoken.”[xiv] And place is not just where “I” am, rather it is where “I” do. In the possibility of “doing” with(in) a space/place, “I” am.[xv] Memory of the Cactus (dir. Hanna Musleh, 2009), explores both the experience of being in place and that of being in place as displaced.[xvi] Musleh presents the story of three villages whose land was expropriated by Israel following the 1967 war, through the testimony of their Palestinian inhabitants who were forced to become refugees and the corroborating account of Israeli academic and historian, Professor Ilan Pappé. Place and space are seen in the present while invoking a past of dwelling—a before—that is sundered from the present of living–after.

Where Beit Nuba, Imwas, and Yalo once stood, there is now a recreational area called Canada Park, financed in 1973 by the Jewish National Fund of Canada that raised $15 million for the project. It is a celebrated archaeological site because of its ancient Roman ruins, but it also constitutes a more modern “remembering” of the Palestinian homes and thus lives it once sheltered and sustained. The cactus of the title of Musleh’s film was used by the villagers as a marker and barrier between one plot of land and another, and its hardiness and ability to grow again even after being uprooted means that it is now the living memory within Canada Park of those others uprooted but unable to live again on this land. The film follows a group of young Israelis visiting the park to learn of its complex history and Israel’s part in it. As they eat the citrus fruit and almonds of surviving trees, these “now” images of the landscape are intercut with the past of living visualized in photographs, film, and maps, and spoken of in the present through the testimony of their former occupants. They recount not only their forced abandonment of their homes in 1967 and their subsequent survival and loss, but also their lives in each village, remembering fruit trees, the village square that was home to social activity, and the friendliness between villagers and visitors.

Memory of the Cactus (Hannah Musleh, 2009)

Joseph Hochman was with the Israeli Defence Forces in 1967, he is interviewed in the film in Canada Park

Aisheh from Yalu remembers her village

At Canada Park, Hagai Matar explains the role of the cactus

We become engaged by a temporality that Deleuze calls “sheets of past” and “peaks of present”[xvii] that produces alternative and irreconcilable meanings in the landscape of Canada Park’s insistent remembering of both its ancient and modern past of expulsion. For its ancient stones betoken the time of Roman rule, and thereby also the expulsion in AD 135 of Jews from Israel.

These documentaries enable us not just to know the facts and the people, but also to know differently, outside of the regimes of knowledge that depend on a discourse of objectivity, and of an “over there” to be known by us “over here.” It is to apprehend what cannot be documented as such but must come to be known in a process of engagement with the seen and heard of the shown and spoken as a “here” in me that psychoanalysis understands as identification. Space is both place and its lived experience articulated in the stories told; we may identify with the storyteller as subject of loss—and thence with her hopes of a future otherwise, of the lost regained—in a relation of “as if,” for we too might fear such loss, such disempowerment and want to have hope. The time-image for Deleuze is a process of thinking the undecidable and contingent, but I want to include here not a perception (the term that is central to Deleuze’s schema), but an apprehension—of an unrepresentable that Jacques Lacan termed “the Real” that undoes thought and which is felt as loss.[xviii]

The documentary time-image engages us with the contingency of life lived, opening us to a duration of thinking, of the virtual, in a process of sense-making that remains incomplete, uncertain. It is in this uncertainty that a thinking otherwise can also arise, and one that involves thinking two things together, and of the possible that might be.

In James Benning’s El Valley Centro (2000), which focuses on California’s Central Valley, 550 miles long and 60 miles wide, such uncertainty and the possibility of thinking otherwise arises in the present time and duration of remembering and reflection in relation to a landscape that, re-seen, is re-made as the space of ownership and of capitalist enterprise. Together with Los (2001), on greater Los Angeles, and Sogobi (2002), a study of the Northern California wilderness, El Vally Centro constitutes Benning’s’ “California trilogy.” Each consists of 35 shots lasting 2.5 minutes, filmed from the same fixed position camera-setup, with a final title sequence lasting 2.5 minutes. Until the title sequence, the film consists of a series of landscape portraits whose closed and formal structure allow quiet contemplation, enabling us, the viewers, to look around the scene, knowing the duration, awaiting the changes we expect within a landscape with which we are becoming familiar, that will nevertheless give rise to the unexpected. In one sequence shot a freighter ship suddenly enters rear frame and passes horizontally across, followed by a sailboat, each travelling on the Stockton Deep Water Channel that we later can put a name to but that we cannot discern within the view Benning has chosen for us. The frame becomes dynamic through such movements across and within the frame; in one shot, a hayraker begins as just a small speck in the distance that, having travelled forward toward us in the frame, abruptly turns offscreen right. It is still present to us in the sounds of its engine until it re-emerges elsewhere in the field (prompting the memory of another cornfield, in Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, 1959). In another shot, a train enters after just a few seconds, again passing horizontally, filling up the image. It evacuates the landscape it occupies, while creating a rhythm of movement and vision in the repetition and differences between its freight cars. Its enormous length begs the question: will it cross before the end of the shot, or not? Sounds of noise or voices, their source often unseen, open up the framed space to the continuousness of a world beyond yet not visually included. The camera is an observing eye, unacknowledged except, perhaps, in the apprehensive glances that seem to be addressed to us by migrant fruit pickers working beside an overseer. Our pleasure is in seeing with the camera, in a seeing again, and seeing what Benning could not necessarily know might happen and what he might only later—reviewing—have seen as we do now.[xix]

El Vally Centro (James Benning, 2000)

All this is placed in parentheses by the final title sequence that, in naming what we saw, challenges our own “naming,” our cognitive perception. The titles identify the subject matter, its owner, and the location of each shot. For instance the titles for shots 5, 6, 18, and 27 read: “hayraker, Tejon Ranch, Arvin,” “freight train, Southern Pacific, Bakersfield,” “dredge, Delta Dredging Co., the Delta,” and “freighter ship, Naviera de Chile, Stockton Deep Water Channel.” This information, displaced from its referent, the filmed sequence, becomes a deferred that is not missed until we arrive at it in the film’s conclusion. It thereby becomes, retrospectively, suspended information that circumscribes the seen and heard in terms of a named subject represented, a specific location that could be revisited and an ownership that introduces relations of the propertied and the propertyless into the landscape. Benning has said that he wanted

to code and then cause a rereading of the whole film by naming what you see and exposing ownership. Like, you might not know that this was a cotton picking machine, and almost all of the land is owned by the large corporations, like railroads, or oil companies, banks, causing a political reading. … Not only do I want to bring out the politics, but I want the viewer to recall the whole film, to play with memory.[xx]

The intervals between the shots that were before a series only by virtue of their sequence in the time of our viewing become afterward gaps for the missing title that we can now insert. What is cited as the content of the shot, however, is partial, a selection and, hence, an assertion, for the hayraker exists within a field and a sky, and it has a driver. The process of mental review that the film demands becomes a political act of understanding that what we had taken to be—had possessed as—landscape views now become owned by others as places and sites of labor, of community, and of property. The captioning reduces a polysemy we had enjoyed and now remember while suffering our failure—indeed the impossibility—to remember and remake the film with this new information, for it cannot displace our first reading, instead it becomes “the method of AND, ‘this and then that,’.”[xxi] The series is remade into a before of landscape and an after of the titles between each view that are two distinct temporalities of cinematic experience. A different interval now arises, for the title does not join the image into a unity, nor join it to its neighbors, while it breaks the unity of the shots as members of the series. It is, in Deleuze’s sense, “irrational,” opening a virtual of thought that is not resolved within the image and not held to it, engaging us, in our passage between that becomes a direct image of time, to think otherwise. [xxii]

In this essay I have brought together two landscapes and their spaces in documentary films that engage us as time-images but which are also documents of being in place and thus demonstrate, in Massey’s words quoted earlier, that places “are not ‘given’—they are always in open-ended process. They are in that sense ‘events’.”

Notes

[i] Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Hammerjam (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), and Cinema 2: The Time Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989). Deleuze does not distinguish documentary from fiction film; in Cinema 1 his references are to Dziga Vertov’s montage of intervals (39), and poetic or abstract works of Joris Ivens (110) and Michael Snow (122) in producing “any-spaces-whatever,” both concepts developed in Cinema 2 in relation to the time-image. There he develops an extended discussion of documentary “cinema of the lived,” in works by Shirley Clarke (130), Jean-Luc Godard, and Jean Rouch as new forms of story in relation to his thesis of the “powers of the false”(126-155).

[ii] Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time Image, 39.

[iii]Ibid., 37-38.

[iv] David. N. Rodowick, Gilles Deleuze’s Time Machine (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1997), 86. Particular forms of indeterminancy and paradox are introduced by the time-image in relation to truth and falsity. In documentary the referential is not fictional, but nor is it simply true. Judgement of different possible interpretations of the past and the present as necessary or contingent confronts an “incompassability,” two things, events, or worlds cannot both exist, both be “true.”

[v] Sigmund Freud, ‘The Uncanny’ (1919), The Standard Edition of the Complete Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 17, 217-252.

[vi] My discussion of Port of Memory and Hanna Musleh’s two films draws on my presentation at Visible Evidence, 16, Istanbul 2010. I am grateful to the London Palestine Film Festival, and to Hanna Musleh for access to these films. My discussion of El Valley Centro is drawn from chapter 6 of my book, Recording Reality, Desiring the Real (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011).

[vii] Explored more fully by Doreen Massey in her book, For Space (London: Sage, 2005).

(http://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/the-future-of-landscape-doreen-massey/)

[xiii] Raja Shehadeh, The Third Way: A Journal of Life in the West Bank (London: Quartet Books, 1982). See also Shehadeh’s Palestinian Walks: Notes on a Vanishing Landscape (New York: Scribner, 2007).

[ix] Viewable at http://www.kamalaljafari.com/#!vstc4=films-gallery/vstc1=port-video.

[x] Shehadeh, The Third Way, 86-7.

[xi] Hamid Naficy, “Palestinian Exhilic Cinema and Film Letters” in Dreams of a Nation: On Palestinian Cinema, ed. Hamid Dabashi, (London: Verso, 2006). Such accenting signifies “both the deterritorialized existence of the filmmakers and the films’ artisanal and decentered conditions of production” (90). Palestinianess is experienced and made through the experience of the Nakba, so that it (and Palestinian cinema) is, since 1948, “structurally exhilic” in Naficy’s words (91).

[xii] Hanna Musleh was trained as an anthropologist in Moscow, then studied visual anthropology at Manchester University. His films, made in Palestine and funded through NGOs, give time to their participants to speak and be seen in place.

[xiii] Deleuze, Cinema 2, 150. Deleuze is here referring to Pierre Perrault’s term for the new direct filming of sync sound and image of life lived that, with Jean Rouch’s cinéma vérité became known as direct cinema.

[xiv] Martin Heidegger, “Building, Dwelling, Thinking,” in Poetry, Language, Thought, translated by Albert Hofstadter, (New York: Harper Colophon Books, 1971), 157.

[xv] Edward S Casey, The Fate of Place (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998), 232.

[xvi] Memory of the Cactus can be watched on YouTube at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wik43djz3M4

[xvii] Deleuze, Cinema 2, 99 and 100.

[xviii] Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, 53-54. I have explored this more fully in Recording Reality, Desiring the Real, 121-126.

[xix] Benning selected these shots from the many he took, returning to a scene of a fire burning several days later to film again. He did, however, edit the sound, to more fully express his own experience of the landscape and place in the scene. See the interview with Benning at the Los Angeles Film Forum, Q&A Pt. 1 - May 27, 2007.

[xx] Cited by Jonathan Rosenbaum in his review in Chicago Reader (14 March 2002), and http://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/california-trilogy/Content?oid=907971.

[xxi] Deleuze, Cinema 2, 182.

[xxii] Deleuze, 182. This concept is explored eloquently by D. N. Rodowick in Gilles Deleuze’s Time Machine, 143.

Elizabeth Cowie is Professor of Film Studies at the University of Kent, UK. She is co-founder and co-editor of m/f a journal of feminist theory, and published Representing the Woman: Cinema and Psychoanalysis, in 1997. She has written on film noir, on the horror of the horror film, on the cinematic dream-work, and most recently on the documentary film in Recording Reality, Desiring the Real (University of Minnesota Press, 2011).

Media Fields Journal

Media Fields Journal

Reader Comments