Expectations: Trans Youth and Reproductive Politics in Public Space

Monday, December 2, 2013 at 3:17PM

Monday, December 2, 2013 at 3:17PM Toby Beauchamp

[ PDF Version ]

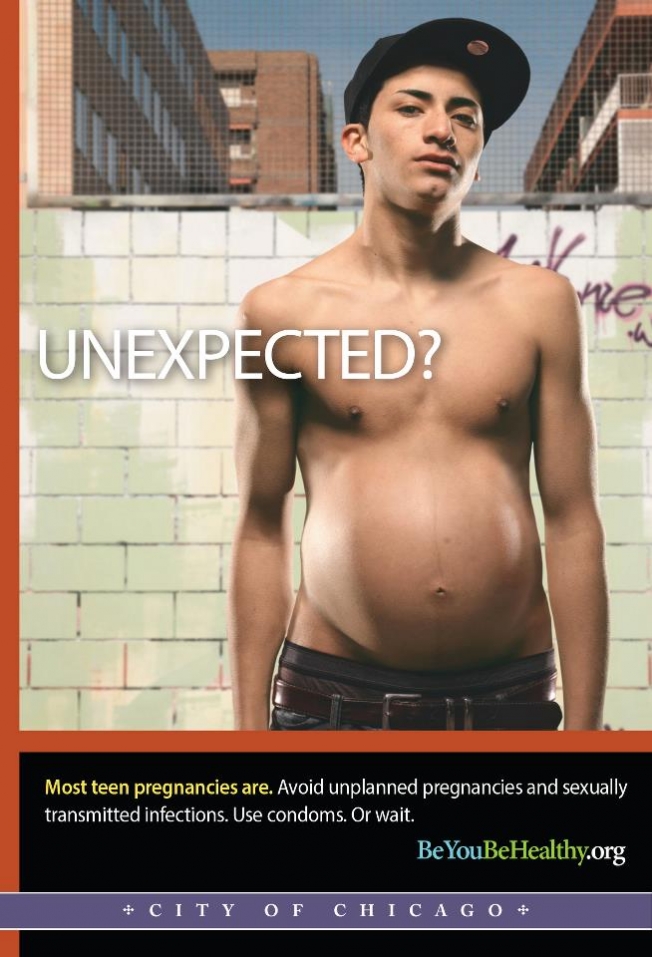

In May 2013, the Chicago Department of Public Health’s Office of Adolescent and School Health launched a new public advertising campaign on teen pregnancy prevention. The campaign, informally titled “Unexpected” and appearing primarily on public transportation, features images of visibly pregnant teen boys along with the copy “Unexpected? Most teen pregnancies are. Avoid unplanned pregnancies and sexual transmitted infections. Use condoms. Or wait.” According to the CDPH, the ads are designed to be “attention-grabbing” and to “spark conversations among adolescents and adults” in an effort to reduce Chicago’s teen birth rate, currently one of the highest in the United States.[1]

Figure 1.

The ads, which the CDPH itself describes as “provocative,” appear alongside other recent media campaigns about teen pregnancy, such as New York City’s “The Real Cost of Teen Pregnancy” advertisements on public transit and bus shelters this spring, which featured pictures of unhappy toddlers alongside statistics such as high school drop-out rates and child support costs for teen parents.[2] The NYC ads were heavily criticized for shaming and stigmatizing teen parents and for failing to offer actual preventative resources or promote comprehensive sex education.[3] Many of these critiques emerged from teen parents themselves, who argued that the campaign used statistics for shock value without attending to the realities of their lives. Similarly, the Chicago ads overtly use the shock of an apparently impossible pregnant body in ways that necessarily evoke yet also suppress the existence of transgender youth. CDPH Commissioner Bechara Choucair explains in an interview that “improving the health and well-being of our youth is a key component in our comprehensive effort to make Chicago the healthiest city in the nation.”[4] Yet we might ask which youth are absent from this effort, even as their images make possible the campaign’s visual power. The pregnant boy public health campaigns circulate in the broader context of state surveillance and punishment of transgender and gender-nonconforming youth, particularly as those youth inhabit public space. As such, the ads appear successful not simply because they present an unexpected image, but because the supposedly impossible images of pregnant boys work in tandem with the routine scrutiny and regulation of gender-nonconforming youth in public space. That is to say, the ads present seemingly unthinkable bodies in the very settings in which such bodies are regularly exposed and policed.

The CDPH actually drew on ads that first appeared in a similar campaign in Milwaukee in late 2007, using the same images with different text. The ads were originally created by Serve, the all-volunteer charitable arm of the larger for-profit independent advertising agency BVK, with a mission of giving “under-served charitable causes a stronger voice in the community.”[5] Funded by the United Way of Greater Milwaukee and designed in connection with a broader public education campaign called One Milwaukee, which bills itself as “a citywide initiative to help bridge the gap between the haves and haves-not,” these particular ads are directed at Milwaukee’s teen pregnancy rates, recently found to be among the highest in the United States.[6]

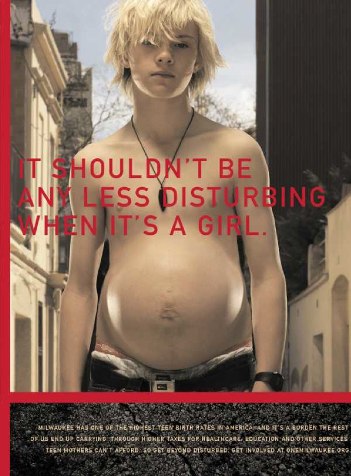

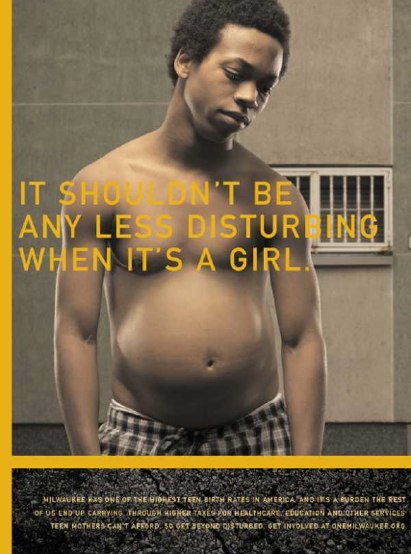

Figure 2.

The ads, designed for outdoor display on billboards and public transportation, each feature one of three teenage boys. Each boy is shirtless, and each has a visibly distended abdomen, marking him as pregnant. In Milwaukee, the main copy is written across each boy’s chest and reads, “It shouldn’t be any less disturbing when it’s a girl.” In Chicago, the single word “Unexpected?” appears in large print, with smaller copy reading, “Most teen pregnancies are.” While these elements are common to all three ads, each ad is distinct in the way it is visually marked by class and race. The boy with light skin and shaggy, bright blond hair appears in the sunny outdoors, in one ad standing with skyscrapers and trees in the background, in another ad lounging on a skateboard. He looks unsmilingly into the camera, but a lock of hair across one eye softens his gaze (see Figure 2). A graffiti-inscribed brick wall frames a second boy who has darker skin and eyes, and through the chain-link fence above his head, tall buildings surround a thin wedge of blue sky (see Figure 3). Wearing a dark baseball cap, he too looks directly into the camera, chin raised so his gaze is directed down onto the viewer, projecting an air of confidence or perhaps a sense of challenge. The third boy, who reads as black, is the only one not clearly positioned outdoors. He stands in front of a wall that extends to the very edges of the frame, empty but for a small window fitted with security bars. While the other two boys wear jeans, he wears what might be pajamas or sweatpants with grey and white stripes, and rather than looking into the camera, he gazes at the floor, head tilted away from the viewer.

Figure 3.

It is not difficult to read these images as different representations of race and class within an urban backdrop, perhaps most obviously in the ways that a carceral setting frames the figure of sexually deviant black male youth. As a series, the ads’ surface-level homogeneity—their composition and textual similarity—seems designed to sublimate race and class difference in order to emphasize the seemingly shocking and impossible bodily characteristic that they have in common. The shared text for the Milwaukee ads—“It shouldn’t be any less disturbing when it’s a girl”—assumes first that the viewer is disturbed by visible pregnancy in someone perceived to be male, and second that this affective response should be equally present when confronted with the idea or image of pregnancy in a young person perceived to be female. Yet the different visual elements that mark each boy by race and class belie the sameness that the repeated text implies. Thus the disturbed response assumed or provoked in the viewer results not only from the supposed abnormality inherent in an image of a pregnant boy, but also from the notion of non-white, poor, and urban pregnant bodies more broadly.

The visual relationship drawn between teen pregnancy and particular racialized and classed bodies is further solidified by the tag line at the bottom of each Milwaukee ad, which reads “Milwaukee has one of the highest teen birth rates in America, and it’s a burden the rest of us end up carrying, through higher taxes for healthcare, education, and other services teen mothers can’t afford. So get beyond disturbed. Get involved at OneMilwaukee.org.” Linking teen pregnancy to economic stress, the ads position these bodies as deviant drains on both the social body and individual tax-paying citizens. The figure of the pregnant boy signifies here an imperative for the viewer to feel disturbed by a visibly non-normative body that is read as such not only through gender, but through the racialized and classed tropes of the welfare mother and pregnant teen. The public images of these bodies are intended to be unsettling both because the bodies themselves are positioned as non-normative and unnatural, and because they invoke broader understandings of non-normative sexual and reproductive practices that are socially disruptive and economically threatening.

The figure of the gender-nonconforming pregnant body in these public health campaigns depends on its construction as anomaly in order to produce and reproduce ideals of normative reproduction in contrast. That is, the image of a pregnant boy “works” precisely because it is understood to be otherwise unthinkable in ways that the image of a pregnant girl is not. Thus, Serve explains its campaign not in terms of race, class, or even gender per se, but rather as a “startling” visual that forces public discussion of teen pregnancy: “How do you fix a 30-year societal problem that no one wants to discuss or hear about. Simple. You start by making the issue impossible to ignore.”[7] The “impossibility” here turns on the presumably fictitious, impossible pregnant boy featured in the ads; Serve’s rationale suggests that viewers cannot opt out of this conversation when confronted by a body so disturbingly unimaginable that it compels public attention.

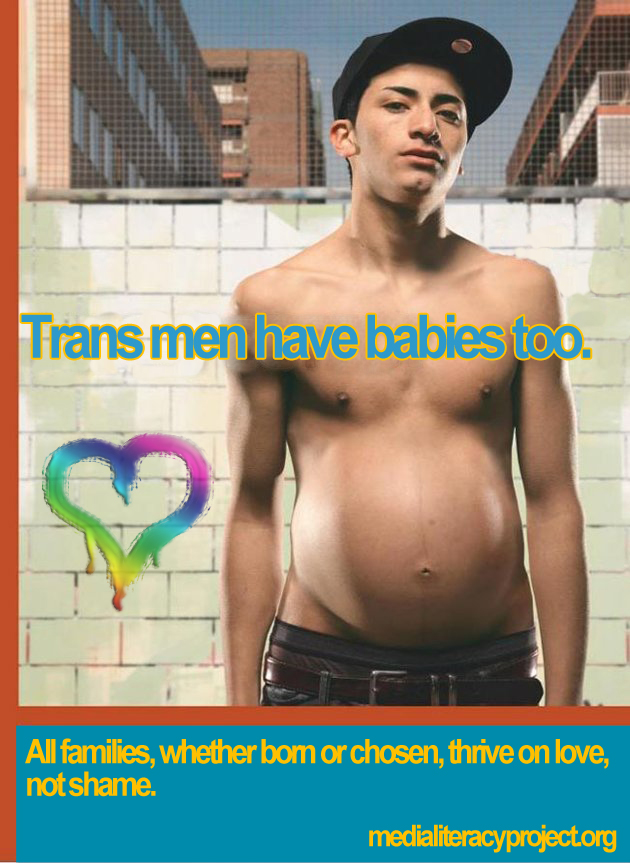

But this apparent impossibility takes for granted a broad public ignorance of transgender bodies, relying instead on a normative conflation of particular reproductive organs and capacities with the category of “woman.” At the same time, that reproductive capacity is forcibly foreclosed for many transgender people who must be surgically sterilized in order to change their legal gender markers.[8] In these ways the ads play on the assumption that transgender populations do not participate in (and in fact are fundamentally disconnected from) reproductive practices, an assumption that makes it possible for a pregnant boy to elicit shock. The Media Literacy Project, an organization that promotes and teaches critical media engagement as part of broader social justice efforts, created a counter ad in response to the public ignorance assumed in CDPH’s campaign (see Figure 4). Adding new text to the pregnant boy image, the counter ad reads, “Trans men have babies too. All families, whether born or chosen, thrive on love, not shame.”[9] This critical reframing refuses the original ads’ implicit shock value and works to increase awareness of transgender populations. While this strategy makes sense from a certain perspective, it also forwards its own implicit assumption that transgender bodies are otherwise invisible to the general public. In fact, the pregnant boys campaigns’ reliance on images of these particular young bodies as otherwise unthinkable and absent from public view masks the extent to which transgender and gender-nonconforming youth, especially youth of color and poor youth, are regularly thrust into public space.

Figure 4.

In part because the private and domestic often refuse them, queer and transgender youth have long inhabited, and organized to change, public space. For instance, discussing the queer and transgender street organization Vanguard in mid-1960s San Francisco, Jennifer Worley notes that the youths’ own social and political context exposed the limitations of liberal gay rights rhetoric based on the notion of consenting adults in the privacy of the home. Vanguard’s work, Worley writes, demonstrated “the woeful inadequacy of this cliché as an appeal for the rights of queer and trans youth who might be consenting but are not adults, who in many cases had been expelled from the protections of ‘the home’ and its aegis of privacy, and who, as street-based sex workers, depended for their very survival upon queer modes of accessing public—not private—spaces for specifically sexual purposes.”[10] Transgender and gender-nonconforming youths’ sexual practices were thus necessarily situated in public space. More recently, youth-led social justice organizations such as FIERCE in New York City resist the privatization of public space and call for vibrant public services, explaining that “LGBTQ youth of color are ushered out of our homes, schools, and safe spaces every day as access to vital resources and opportunities decrease.”[11]

FIERCE is among several organizations challenging the ways that state policing practices particularly exert power over transgender youth of color, demonstrating that the home and school are frequently sites of violence and hostility that push youth into public spaces such as foster care, group homes, and homeless shelters. Because these spaces are subject to greater police presence and state surveillance mechanisms, transgender youth are more vulnerable to arrest and incarceration for activities such as sex work or sleeping on sidewalks. As Wesley Ware notes, “queer and trans youth are overrepresented in nearly all popular feeders into the juvenile justice system—homelessness, difficulty in school, substance abuse, and difficulty with mental health,” and thus “it should not be surprising that they may be overrepresented in youth prisons and jails as well.”[12] In these ways, transgender youth, particularly those marginalized by class and race, not only occupy public space but are especially subject to the scrutinizing gaze of both the state and the general public while in that space.

In this sense, the presumably unthinkable body of the pregnant boy in recent public health campaigns—the unruly, gender-nonconforming body meant to appear out of place and surprising—is actually already well established as one embedded in public space and under close observation. We might say, in fact, that the routine surveillance and discipline of gender-nonconforming youth bolsters the ads’ visual power: even while they rhetorically invoke the pregnant boy as impossibility, their demand that viewers be “disturbed” and “get involved” in monitoring these bodies simultaneously builds on the many ways that transgender youth already appear as targets of state and public scrutiny. Rather than appearing in television commercials or magazines, the ad campaign targets public transportation, bus shelters, billboards, and other public sites: those public spaces in which transgender youth are perhaps most exposed and most subject to policing practices. Along with the urban public settings depicted in the images themselves, the ads’ placement in particular spaces focuses anxiety about non-normative reproductive practices on those populations least able to access private housing, transportation, or healthcare—and thus those for whom a certain measure of bodily privacy is often already foreclosed.

Though ostensibly created to improve young people’s health, the pregnant boy ads rely on the public’s refusal and rejection—in tandem with its routine scrutiny and discipline—of certain young bodies marked as deviant. Because presumably nothing and no one “real” stands behind the image of the pregnant boy, this figure can signal or provoke anxieties about deviance and degeneracy without necessarily overtly referencing the racialized, classed, and gendered bodies typically associated with those characteristics. Yet in doing so, the ad campaigns continue the longstanding surveillance of reproduction in which all pregnant bodies are public bodies, classified by medicine, law, and media as fit or unfit, normative or deviant.[13] Positioning the image of a pregnant boy as anomalous effaces this history, even while it provides the very groundwork for the public fascination, repulsion, and moral scrutiny of particular reproductive bodies in the first place. By presenting these bodies as impossible, the campaigns obscure not only the routine scrutiny and punishment of gender-nonconforming youth, but the systemic surveillance and policing of reproduction for all bodies.

Notes

[1] “Provocative New Campaign Sparks Citywide Conversations on Teen Parenthood,” City of Chicago, 14 May 2013, Read Here.

[2]“Think Being a Teen Parent Won’t Cost You?” NYC Human Resources Administration, 30 March 2013, Read Here.

[3]“Teen Pregnancy ‘Shaming’ Campaign Slammed by Young Parents,” Storify, 10 April 2013, Read Here.

[4]“Provocative New Campaign.”

[5] “About Serve,” Serve Marketing, 30 May 2013, [6]One Milwaukee, Read Here (accessed 1 June 2013).

[7] “Pregnant Boys,” Serve Marketing, 30 May 2013, Read Here.

[8]For recent discussions of such sterilization practices, see for example Nicole Pasulka, “17 European Countries Force Transgender Sterilization,” Mother Jones, 16 February 2012, Read Here.

[9]“Pregnant Boys and a Counter Ad,” Media Literacy Project, July 8, 2013, Read Here.

[10]Jennifer Worley, “‘Street Power’ and the Claiming of Public Space: San Francisco’s ‘Vanguard’ and Pre-Stonewall Queer Radicalism,” in Eric A. Stanley and Nat Smith, eds., Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex (Oakland, California: AK, 2011), 50.

[11]“Our S.P.O.T. Campaign,” FIERCE NYC, 4 June 2013, Read Here.

[12]Wesley Ware, “Rounding Up the Homosexuals: The Impact of Juvenile Court on Queer and Trans/Gender-Non-Conforming Youth,” in Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex, ed. Eric A. Stanley and Nat Smith (Oakland, California: AK, 2011), 82.

[13]For example, Rickie Solinger’s history of reproductive practices and policies in the United States describes how marginalized people’s reproductive practices have long been a matter of public scrutiny, but even racially and economically privileged bodies have typically had to maintain a certain standard of health and normative family structure that could stand in contrast to the bodies and families of the poor, disabled, and non-white. Private pregnancies, in this light, were only private insomuch as they could maintain a public image of fitness, morality, and heteronormativity. Rickie Solinger, Pregnancy and Power: A Short History of Reproductive Politics in America (New York: New York University, 2005). For further discussion of the public pregnant body, see for example Anne Balsamo, “Public Pregnancies and Cultural Narratives of Surveillance,” in Revisioning Women, Health, and Healing: Feminist, Cultural, and Technoscience Perspectives, ed. Adele E. Clarke and Virginia L. Oleson (New York: Routledge, 1999), 231-253; and Dorothy Roberts, Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty (New York: Pantheon, 1997).

Toby Beauchamp is assistant professor of Gender and Women's Studies at Oklahoma State University. His work focuses the critical lens of transgender studies on questions of state power, science, and technology, and transnational flows of bodies, knowledge, and capital. He is currently completing a book manuscript entitled Going Stealth: Transgender Politics and U.S. Surveillance Practices.

Reader Comments