Learning to Ignore Sirens: The San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station as Techno-Aesthetic Object

Monday, June 17, 2019 at 2:54PM

Monday, June 17, 2019 at 2:54PM Jack Manoogian

[ PDF Version ]

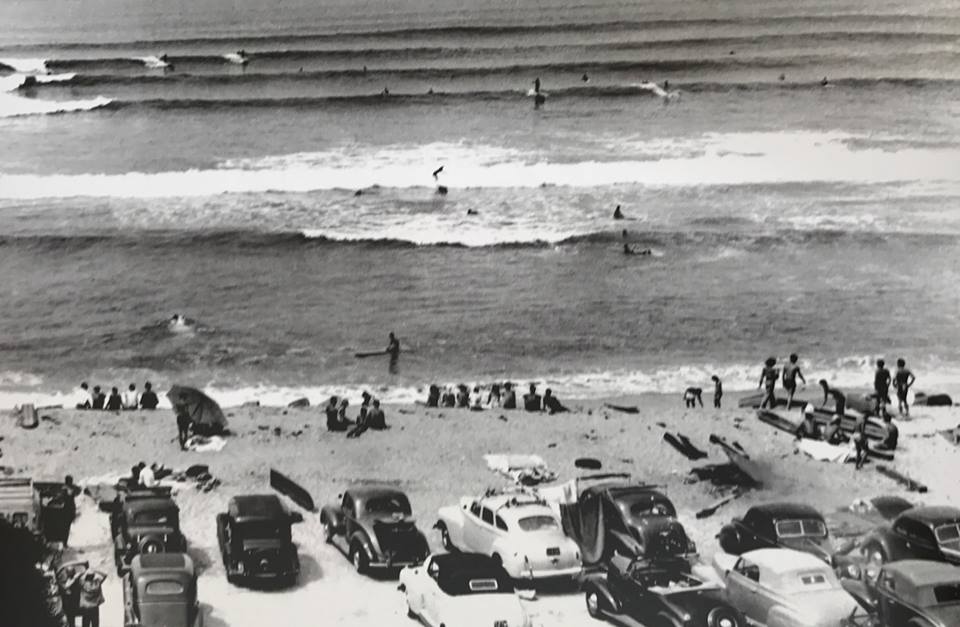

Figure 1. “A lot has changed in the 80 years since this photo was taken, but there is always fun to be had at SanO and the beauty of the waves is still the same.” San Onofre Surfing Club Facebook Page, 3 August 2017.[1]

Figure 2. Surfer at San Onofre State beach, Mark Rightmire, Orange County Register, 17 April 2017.

In Southern California, on the forty miles of coastline between Los Angeles and San Diego known as Orange County (the OC), sits one of the most popular surf breaks in the world: San Onofre State Park, or SanO, as locals call it. SanO is located in the town of San Clemente, two towns south of Laguna Beach, where I grew up. My friends and I learned to surf at SanO and we continued surfing there throughout our adolescence at a break just north known as Trestles. Trestles is a world-class break, home to the September stop of the World Surfing League Championship Tour. (The WSL tour is what the MLB is to baseball or the NFL to football.)

I surfed Trestles for about six years, and at least once per season I was shaken off my board by the jarring reverberations of a siren wailing behind me, warning of a nuclear meltdown. The sirens belonged to the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS), which operated on the shores of San Onofre State Beach from 1967 to 2013. As the siren began droning, my stomach would rise into my throat and I would look to my fellow surfers—a pack of us about a quarter mile from shore. The surfers around me would feign indifference at what was undoubtedly another test of the emergency system. Surfing is, after all, an “extreme” sport, a sport wherein one willingly leaves the safety, security, and solid footing of land for the uncharted depths of ocean. In the end, the San Onofre plant never experienced a meltdown. Yet I find something deeply troubling in the way that my fellow surfers and I could enact such apathy towards the alarms.

The power plant is an example of what media theorist Lisa Park calls an “infrastructural imaginary.”[2] Parks writes that “such an imaginary might begin with . . . the general tendency of infrastructures to normalize behavior (such that they become relatively invisible and unnoticed), and, on the other, as the potential for disruption of that normalization, which occurs during instances of inaccessibility, breakdown, replacement, or reinvention.”[3] Through repetition, the SONGS alarms became banal—another audio backdrop to a surf session. Much like the ceaseless crashing of waves against sand, the sirens were incorporated into the surfers’ imaginary of what it meant to surf the waves at Trestles.

I argue that one must consider the infrastructural imaginaries of the SONGS site. To this end, I find French engineer and theorist Gilbert Simondon’s concept of the techno-aesthetic to be immensely useful. In an unsent 1982 letter to Jacques Derrida, Simondon formulates the techno-aesthetic object as “perfectly functional, successful, and beautiful. It’s technical and aesthetic at the same time: aesthetic because it’s technical, and technical because it’s aesthetic. There is intercategorial fusion.”[4]

Considering the infrastructural imaginaries of the SONGS site as well as the technological and aesthetic nature of the plant queers the distinction between the hard machine and the soft beauty, between the physical and the affective. Geographically and ecologically, the plant affects the surrounding land; it is situated in a precarious marine ecosystem and sits just one hundred feet from the ocean. But how does the plant register, in an affective sense, with the human and nonhumans who come into contact with it?

This essay aims to create a site-specific study that enacts, materializes, and contextualizes the work of theorists who have come to seriously consider the affective and ecological stakes of nuclear infrastructure and media objects. This is an exploration into how a particular community has formulated an imaginary that allows its members to live on and at the edge of an apocalyptic system of nuclear energy production and subsequent waste disposal. I aim to question the ontological structures of these imaginaries and to explore the stakes and consequences of surfing, growing, and living at the edge of nuclear precarity.

It is essential that one understand the turbulent history, development, and final shutdown of the plant. In this way, one comes to see the numerous disparate forces that have worked in concert and discord throughout the plant’s history.

SONGS began operating on 17 June 1967. It was called a win for the state by the federal government as well as Southern California Edison (SCE), the company that owned and operated the plant.[5]

Unit 1, the sole nuclear generator when the plant first began service, ran from 1967–92. During this period, Unit 1 had serious mechanical issues that caused the entire plant to shut down at least four times, for periods as short as thirteen weeks and as long as fourteen months.[6] By 1984, SCE had built two more generators, Units 2 and 3. In November 1992, Unit 1 was deemed too expensive to maintain and was shut down. This decision was likely informed by a 1988 California Coastal Commission (CCC) study which required SCE to pay reparations for damages to marine life in the area directly surrounding the plant.[7] Twenty-one years later, in 2009, Unit 2 was taken offline for planned replacement of a steam generator manufactured by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI). Unit 3 was taken offline for the same reasons the following year. It cost roughly $670 million to replace the steam generators for both units. Chaos ensued in late January 2012 following a radiation leak in Unit 3 which resulted in a complete shutdown of the plant. Further investigation revealed that the tubing of the new MHI generators on both units had deteriorated significantly. Still offline in 2013, SCE estimated that repair costs for both units and the losses caused by the lengthy shutdown amounted to $553 million in total. SCE announced plans to close the plant on 7 June 2013 and was licensed to begin the decommissioning process on 12 June of the same year.[8]SONGS’s history is one of mechanical and social difficulties. Perhaps the most pressing and opaque problem is the radiation leak in Unit 3 from the botched MHI generator. The leak is said to be the reason for numerous dubious backroom meetings that have occurred between SCE board members, the CCC, and other officials in relation to the plant’s decommissioning.[9] Professor Daniel Hirsch, head of the Program on Environmental and Nuclear Policy at UC Santa Cruz, stated that “a meltdown could result in as many as 130,000 immediate deaths, 300,000 cancers and 600,000 genetic defects.”[10] SCE followed protocol, shutting down the plant after the leak. However, the subsequent decommissioning process, which is estimated to cost $4.77 billion, has been handled less professionally.

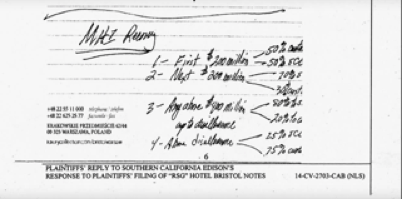

In the thirty-eight-minute-long YouTube video, “San Onofre $5 BILLION Cover-up w/ Mia Severson,” San Diego attorney Mia Severson argues that SCE and the CCC have conspired to pass the cost of the SONGS failure and shut down onto the public. In the video, Severson reveals that in 2015, SCE was fined $16.7 million as a result of a meeting between then-President Michael Peevey and Edison executive Stephen Pickett in a hotel in Warsaw, Poland. The two are said to have formulated plans that would put the financial brunt of the decommissioning process on citizens.

Figure 3. The above photos are handwritten notes on “Hotel Bristol” stationery—the Warsaw hotel where Peevey and Pickett met. The notes closely resemble the financial plan for decommissioning SONGS that was later decided upon in the California courts.[11]

Additionally, SONGS is now responsible for 1,800 tons of radioactive waste.[12] Currently, the spent fuel from Unit 1 is stored using a dry cask system while that from Units 2 and 3 sits in cooling pools, bound for a similar fate. The 890,000 spent fuel rods at the site are an active threat to the eight million people who live within fifty miles of SONGS.[13] Tom English, former advisor on high-level nuclear waste disposal to President Jimmy Carter, claims that the burying and dry-casking of the waste, a mere one hundred feet from the ocean, subjects the waste to corrosion as sea levels rise. English stated, “The choices made here [at SONGS], were awful—far worse than leaving it [the waste] in the fuel pool.”[14]

Figure 4. Lisa Parks, “Media Infrastructures and Affect,” Flow, 19 May 2014, www.flowjournal.org/2014/05/media-infrastructures-and-affect.

The history of the SONGS plant is convoluted, complex, and at times entirely nonsensical. The result is that now 1,800 tons of radioactive waste lay on pristine Southern California oceanfront real estate. One must wonder: What are the social, political, and aesthetic mechanisms at work that have enabled eight million Orange Countians to live in the face of intense nuclear precarity? And what does living under such circumstances suggest about human resilience in this late-capital period of ecological and nuclear precarity? Does life go on as usual? What, exactly, is life as usual in nuclear times?

We ought to consider how the SONGS plant has been incorporated into the OC imaginary. Parks claims that considering such imaginaries allows for “further thinking about the range of ways people perceive and experience infrastructures in everyday life and how these experiences differentially orient or position people in the world.”[15]

A simple Google search of the San Onofre plant results in seventy-nine Google reviews, a majority of which are crass comments that liken Units 2 and 3 to a woman’s breasts.

Figure 5. Google reviews for San Onofre Nuclear Power Plant.”

The reviews themselves (averaging a fairly decent score of 3.9 out of 5 stars) suggest that the plant has been incorporated into the community’s imaginary much like a restaurant or a hiking trail—a structure whose value resides in its appearance as well as its use: a techno-aesthetic object. The majority of the Google reviews feminize the plant and welcome its presence: “They look like boobs.” “These guys had some ‘bomb’ weed man.” “This place was electrifying.” “I get tired when I drive and seeing a nice set of boobs wakes me ‘straight up’ if you know what I mean. So I’m happy that it is here and so close to the freeway.”[16] If the technological is traditionally coded as masculine and the aesthetic as feminine, what might it mean for SONGS to be both at once? Now that the “technological” functionality of the plant has been shut down, is it only useful insofar as it is an aesthetic object?

There is something much deeper and darker that underlies the sexist jokes which surround the plant. I believe the reviews are an example of the nuclear resilience discussed by Nicole Shukin. Shukin argues that “positive thinking, and feeling, become a trait of resilient subjectivity and a resource of the nuclear economy . . . the depoliticized, resilient subject [is hailed] into being by reassuring the [subject] that so long as they keep ‘smiling’ they won’t suffer any negative effects from radiation.”[17] As I surfed and the sirens rang out behind me, it seemed all I could do was keep my eyes on the sea, to watch for the next set of waves, to keep smiling.

Demographically speaking, it is odd that the citizens of Orange County would be subject to such a precarious situation. The towns directly bordering the plant, San Clemente and Laguna Beach, both have populations that are over 80 percent white with median incomes of $87,184 and $94,325 respectively.[18] It is no stretch to say that in the United States, white and wealthy bodies are considered the most valuable from an economic, social, and political perspective. Yet still, 1,800 tons of nuclear waste sit trapped on the OC shores. Perhaps SONGS, in both a technological and aesthetic sense, has been incorporated into the OC community because of a naïve and cliché, though hopeful, “California, sunny and problem-free” state of mind.

Does the aesthetic act as a force which enables nuclear resilience in Orange County communities, a resilience that “returns [citizens] to the world of circumstances with a certain benevolence toward [such circumstances]”?[19] Meanwhile, the technological continues its own type of devastating work . . .

In Orange County, major radiation leaks, backroom meetings in Warsaw, and the potential for a total poisoning of surrounding marine and land ecosystems have become issues of comparable seriousness to whether or not there will be traffic on the 405 the following morning. What else can you expect? “Orange County, California envelops you in the ultimate Southern California lifestyle . . . here you’ll be immersed in the real California dream.”[20]

Notes

[1] Mark Rightmire, “Spent Nuclear Waste Burial Halted at San Onofre until NRC Can Probe ‘Near Miss’ with Canister,” Orange County Register, 24 April 2018, www.ocregister.com/2018/08/24/spent-nuclear-waste-burial-halted-at-san-onofre-until-nrc-can-probe-near-miss-with-canister/.

[2] Lisa Parks, “Media Infrastructures and Affect,” Flow, 19 May 2014, www.flowjournal.org/2014/05/media-infrastructures-and-affect/.

[3]Ibid.

[4]Gilbert Simondon, “On Techno-Aesthetics,” trans. Arne De Boever, Parrhesia 14 (2012): 1–8.

[5] “Timeline of San Onofre Plant’s Operations,” San Diego Union Tribute, 7 June 2013, www.sandiegouniontribune.com/sdut-history-san-onofre-power-plant-timeline-2013jun07-htmlstory.html.

[6] Jeff McDonald, “It’s Not Just the Steam Generators That Failed,” San Diego Union Tribute, 30 January 2016, www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/watchdog/sdut-san-onofre-anniversary-2016jan30-htmlstory.html.

[7] Jeff McDonald, “Regulators Fined Utility for Not Reporting Meeting, Then Argued It Was Legally Permissible,” San Diego Union Tribute, 22 November 2017, www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/watchdog/sd-me-cpuc-meeting-20171122-story.html.

[8] “There’s No Great Answer for Nuclear Waste, but Almost Anything Is Better than Perching It on the Pacific,” Los Angeles Times, 11 September 2017, www.latimes.com/opinion/editorials/la-ed-nuclear-waste-storage-20170911-story.html.

[9] Mia Severson, “San Onofre $5 BILLION Cover-up w/ Mia Severson,” YouTube, 1 June 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=mExjeoQAXq8.

[10] Jeff McDonald, “It’s Not Just the Steam Generators That Failed.”

[11] Severson, “San Onofre $5 BILLION Cover-up w/ Mia Severson.”

[12] Ralph Vartabedian, “1,800 Tons of Radioactive Waste Has an Ocean View and Nowhere to Go,” Los Angeles Times, 2 July 2017, www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-stranded-nuclear-waste-20170702-htmlstory.html.

[13] “There’s No Great Answer for Nuclear Waste.”

[14] Amita Sharma, “Nuclear Expert Slams Edison’s San Onofre Nuclear Waste Storage Plan,” YouTube, 30 June 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=FnKQjaOWvYg.

[15] Parks, “Media Infrastructures and Affect.”

[16] San Onofre Nuclear Power Plant Google Reviews, www.google.com/maps/place/San+Onofre+Nuclear+Power+Plant/@33.3689333,-117.5569803,17z/data=!3m1!4b1!4m7!3m6!1s0x0:0xd83c2fae10afbbdc!8m2!3d33.3689333!4d-117.5547916!9m1!1b1/.

[17] Nicole Shukin, “The Biocapital of Living—and the Art of Dying—After Fukushima,” Postmodern Culture 26, no. 2 (2016), doi:10.1353/pmc.2016.0009.

[18] Deloitte Data Wheel, and Cesar Hidalgo MIT Media Lab and Director of MacroConnections.Data USA: San Clemente, CA. Deloitte Data Wheel, and Cesar Hidalgo MIT Media Lab and Director of MacroConnections.Data USA: Laguna Beach, CA.

[19] Shukin, “The Biocapital of Living—and the Art of Dying—After Fukushima.”

[20] Orange County Visitor Association (OCVA),” Visit Anaheim, https://visitanaheim.org/attractions/orange-county/irvine/orange-county-visitor-association-ocva/.

Jack Manoogian is a graduate of Brown University where he earned a Bachelor of Arts in Modern Culture and Media. His work is primarily concerned with questions of environmental crises, media documentation, cultural studies and literature. He is originally from Southern California and now lives in Brooklyn, NY.

Reader Comments