Measuring Invisibility and Working for Scale: Extras and the Screen Extras Guild

Kate Fortmueller

[ PDF version ]

“Generally speaking, extra work does not need TALENT; it needs TYPE.”[1]

This brief statement from a 1936 Central Casting pamphlet, created to deter would-be stars from registering for extra work, sums up the overall approach toward background casting and, ultimately, compensation. This pamphlet reflected a trend in industry discourse (and popular press headlines) that discouraged aspiring stars from joining the ranks of registered extras with announcements such as “Want to act? Maybe this’ll dissuade you.”[2] Yet despite the best efforts of these articles, the population of extras in Los Angeles has always numbered in the thousands. This phenomenon, which spans the history of the film industry, is summed up in Shelley Stamp’s article, “It’s a Long Way to Filmland.” Stamp argues that the excess of extras emerged around 1913 and stemmed from a number of changes in the nascent studio system, including the shift toward a Fordist mode of production and the movement of production to Los Angeles. In addition to these industrial factors, she also highlights the increased interest in the cult of celebrity and personality as another contributing factor to the growth of extras in Hollywood.[3] The emphasis on personality, rather than training or specific skills, is what led many people to believe that it would be possible for anybody to achieve fame and fortune in the film industry. This undermines the idea that acting is a skill and that performances emerge from a combination of labor and experience. The combination of glamour and the potential to earn money by “being yourself” explains the powerful draw for budding starlets and extras looking to earn some quick and easy money. This emphasis on inherent characteristics, coupled with the growing need for different “types” rather than trained actors, suggests that background casting offered women and people of color a wider range of possibilities for work than did the casting for leading roles.

Heterogeneity within the population of extras required scaled negotiations for their jobs and compensations, introducing several paradoxes in the relationship between extras and their work. If the successful extra blends into the group and should ideally go unnoticed, how can individual contributions be measured? How can these background performances be differentiated? In practical terms these broad questions were simply answered—the more an extra contributed to the film, through costumes, motorcycles, cars, etc., the more money an extra would make in a given job.[4] As the institutions that catalogued, casted, and supported extras developed, the idea that extras were measured by their intrinsic qualities and pre-existing skills rather than their “talent” became more precisely articulated through pay scales. Despite the large population of extras vying for jobs, and despite the discouraging language propagated by the studios, these pay scales produced an unrealistic expectation for the ability to make a living doing extra work. Central Casting (established in 1925) provided a means to organize the massive workforce of extras and streamlined the casting process, but guild wage scales effectively rationalized extra work. Although extras seem like an overly difficult and unruly group which caused a disproportionate amount of labor conflicts, they are an important part of Hollywood filmmaking, both because of their role in enhancing the realism of a scene and their ability to create spectacle (which was especially important in the widescreen epics of the 1950s and 1960s). The fundamental mimetic qualities of cinema demand more than the literary description of background or a mere gesture toward setting; cinema requires the visualization of a (seemingly) complete world, which typically means a world populated by humans. The difficulty of fixing a monetary value on a star, screenwriter, or director is relatively straightforward because their value can be assessed in relation to previous films. Still, in many cases an extra serves the same function as set-dressing. He or she does not change the film or make decisions about its production but enhances the realism of the space and anchors the Hollywood fantasies.

A discussion of extras always has to contend with issues of scope and scale because they are such a large corpus of people. Individual extras have a relatively small role in the final product of a film, but their numbers make them highly visible in Hollywood. Extras were not (and still are not) a uniform group of people, but one of their common elements is their lack of professional training. The nature of extra work, as opposed to that of stars in the studio system, is that it is temporary, casual (non-contracted) day labor. This did not change with formation of the Screen Extras Guild, but SEG did give extras some limited bargaining power, increased their wages, and helped to make extra work more specialized in the sense that studios agreed to hire union extras. The professionalization of extra work coincides with the post-WWII period in which Hollywood studios were dismantling their rationalized division of labor. While extras serve a different function within films and filmmaking, the absence of professional training is one of the key factors of the institutional separation between actors and extras. By considering extras as a separate category, they are effectively disaggregated from “trained” actors, signaling more of a discontinuity between the two groups than is usually assumed in the stardom narratives that have been told and retold in dime novels, short films, and beloved features such as A Star is Born (dir. William Wellman, 1937, George Cukor, 1954, and Frank Pierson, 1976).[5]

Extra wage scales, which were agreed upon by the Screen Extras Guild (SEG) and the Association of Motion Picture Producers (AMPP), helped to limit compensation disputes between studios and labor. If a dispute arose, the union would notify the studio and request footage to verify details about costume or performance. The scale would then be used to adjust the payment. Extras typically requested adjustments based on either performance (for performing bit parts rather than atmosphere or background work) or costume elements (for buying dress clothes or wearing body paint). The presence of SEG helped to make compensation for such issues visible; however, the focus on individual wage issues eclipsed some of the major institutional problems facing extras during the 1950s. Extras were still plagued by the problems of a bloated workforce and unequal distribution of work. Runaway productions only exacerbated this problem.[6]

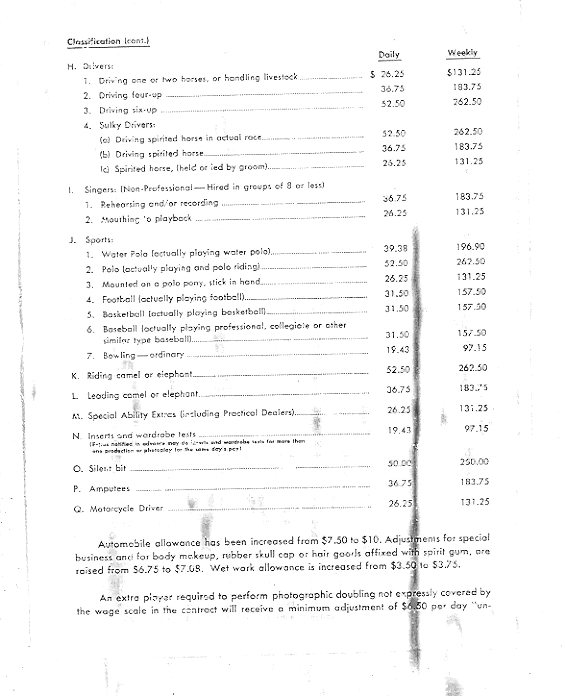

Figure 1. SEG Extras Classifications

In order to compensate extras for their various roles, SEG created different classifications for different tasks. Studios have historically differentiated between regular extras and “dress extras” (extras who provided their own fancy or evening attire), and the union retained these categories, but also expanded the scale to include more active parts (riding, swimming, athletics, etc.). Pay was also distinguished based on difficulty— for example, “riding a spirited horse” paid better than “straight riding.” Although fair compensation is a very important part of a union’s function, this focus on individualization through the creation of specific job categories obfuscated the larger problem facing extras in Hollywood—namely, how to work enough days to make a living from the job.

The Screen Extras Guild pay scale creates the illusion that one can make a good living from extra work. The 1954 revision to the SEG Basic Agreement includes a two-page list of possible jobs explaining the various responsibilities and their accompanying daily and weekly rates. Although the potential weekly earnings would have been appealing, extra work was often sporadic, making the scale misleading. General extra work, which paid $19.43 per day and $97.15 per week, constituted most of the work calls. Among the more lucrative jobs on the list are “riding a camel or elephant” for $52.50 per day, totaling $262.50 per –week—the same rate applies for polo playing and sulky driving. Whereas extra work does not require training, a retail job in 1954 averaged $62.29 per week.[7] To many people, riding an elephant would seem like an exciting, less strenuous, and lucrative way to earn a living, but elephant and camel riding did not constitute the majority of extra work in the 1950s. Even though these scales provide a practical function (they made extras aware of their wages), and the layout on the page makes these rates visually clear, the scales still do not provide an accurate assessment of what extras actually earned over a given period. These rates are ultimately aspirational – few extras were able to make them, let alone become Hollywood stars.

These scales also suggest that casting opportunities and the ability to make a living wage through extra work were both gendered and racialized. Although the discourse surrounding extras calls for a wide and diverse pool of individuals to support the whims of studio filmmaking (a point that is echoed in the Central Casting pamphlet that opens this piece), extras casting actually seems to reflect more general trends in Hollywood casting from the 1950s. As Ann Chisholm points out in her discussion of body doubles, the Screen Actors Guild contracts privileged active doubling (stunt-doubling) over the more common female form of double work (body doubling).[8] This split in SAG work is replicated in extra work. For example, a large portion of the list is devoted to various roles for cowboys and coach drivers in westerns, which favor male extras. These “active” jobs also provide higher wages. Additionally, the allowance for body make-up adjustments (increased compensation for actors who don make-up to look “tanner”), signals a privileging of roles for white extras, even if it means studios paying more money for them. Even though wage scales appear to be an objective manner of measuring labor, the scale reflects not only the presence of certain roles, but the mode in which some skills are more highly valued than others.

The extra vacillates between visibility and invisibility; extras need to be visible as a group, but indistinguishable from others in the crowd, and, most importantly, they need to do their jobs and not interfere with the film production. This description of an extra’s oscillation between visible and invisible in the frame and on-set can be seen as a metaphor for how extras functioned as union and creative labor more generally. The large population of extras often worked against their ability to obtain steady work. SEG’s size as an organization and their pay scale (which was regularly renegotiated) kept extras in a constant state of visibility in the newspapers and the trades, but despite this publicity and their large membership, extras were never able to wield a great deal of power within the studio system.[9] While extras and SEG advocated for fair compensation in the 1950s, the studio system was rapidly changing. Their negotiations for higher wages often provided another financial justification for runaway productions, which were also motivated by the need to use post-war frozen funds and fueled by preexisting studio infrastructure that was set up and made available outside of Hollywood. The Screen Extras Guild attempted to fit within an older (and less mobile) model of the studio system, which limited their effectiveness as a bargaining force within the increasingly global industry. On the whole, SEG was able to function as a viable advocate for the pay scales, but the nature of extra work, their size (as a group), and limited function in films guaranteed that extras were always replaceable, since there was always somebody waiting in the wings to take up a spot in the background.

Notes

[1] “Central Casting Corporation - Facts About Extra Work,” August 1, 1936, Association of Motion Picture and Television Producers Collection, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Beverly Hills, CA.

[2] Ray Hebert, “Want to act? Maybe this’ll dissuade you,” Los Angeles Times, 10 June, 1957, B1.

[3] Shelley Stamp, “It’s a Long Way to Filmland”: Starlets, Screen Hopefuls and Extras in Early Hollywood,” American Cinema’s Transitional Era: Audiences, Institutions, Practices, ed. Charlie Keil and Shelley Stamp, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 333.

[4] This system has not changed. A July 2011 Central Casting job recording explained that they needed women with prams, which qualifies for a pay bump.

[5] For a discussion of stardom narratives in dime novels, see Nan Enstad, Ladies of Labor, Girls of Adventure, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999).

[6] The Screen Extras Guild agreement was valid within a 300-mile zone of Los Angeles and a 75-mile zone of San Francisco.

[7] California Statistical Abstract 1970, Los Angeles: State of California, Department of Employment, 1970, 62.

[8] Ann Chisholm, “Missing Persons and Bodies of Evidence,” Camera Obscura 43, Vol. 15, no. 1 (2000) 135.

[9] In 1954 (the same year as the pay scale under discussion), SEG reportedly had 3,500 members. See “Judge Asked to Decide Jeffers Slander Suit,” Los Angeles Times, 12 February 1954, 2.

Kate Fortmueller is a Ph.D. candidate in Critical Studies at the University of Southern California. Her research interests include issues of labor, unions, background actors, and location shooting.

Media Fields Journal

Media Fields Journal

Reader Comments