Popular Music Memoryscapes of Liverpool 8

by Brett Lashua

“The enthusiasm for seeing a city from the outside is the exotic or the picturesque. For natives of a city, the connection is always mediated by memories.”

-Orhan Pamuk[i]

This essay describes a collaborative documentary film project concerned with the oral histories and collective memories of Black musicians in Liverpool during the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. L8: A Timepiece (2010) focuses on the area of the city designated by the L8 postcode (also known as Granby or Toxteth), historically the socio-geographic heart of the Liverpool’s Black communities. In 1977, an album from local group Real Thing was promoted with the claim that “District ‘8’ is to Liverpool what Harlem is to New York.”[ii] During these years a dense cluster of social clubs emerged in the area, each connected with diasporic African/African-Caribbean cultures, community groups, social events, and music. These clubs, including the Yoruba Club, Nigeria Centre, Ibo Club, Somali Club, Ghana Club, Jamaica House, and Sierra Leone Club, represented important neighborhood foci through the 1980s. Few of these social clubs remain in operation, and most have disappeared completely as the city and its racial relations have undergone dramatic transformations in the last 30 years. Through the use of interviews, the documentary maps memories of L8 and the social clubs that once thrived there. Where were these clubs? What were they like? Who frequented them? Why did they close? By addressing these questions, the documentary engages with the ability of popular music, memory and space (“memoryscape”) to stimulate and sustain conversations about social inequalities, change, and continuity in Liverpool. In this sense documentary may provide an archive for collective memories. The documentary filmmaking process may also recreate spaces and the politics of spatial relations, which—despite widespread changes to the city—continue to trouble Liverpool.

Collective memory, place, & music

Arriving in Liverpool in August 2007, I knew little of the city apart from what I’d picked up from Beatles songs, post-punk records (e.g., Echo & the Bunnymen), films (e.g., Letter to Brezhnev, dir. Chris Bernard, 1985), and photos of the city’s iconic waterfront–texts that comprise popular memories of the city. Popular memories (also called social or collective memory) actively shape cultural spaces and cultural identities. For example, in recent decades, Liverpool has memorialized many spaces in the city linked to the Beatles, and guitar-rock remains the most performed live music in the city. Set against the Beatles’ influence, arguably less attention is given to other musicians, venues, scenes, and musical heritage in Liverpool. Many musicians and sites of musical communities are widely unknown except to the people who participated in, inhabited, and remember them, as Orhan Pamuk notices in the above epigraph.

Music provides powerful links to place. During stressful times of rapid change and uncertainty, popular memories are often recalled by civic and cultural agencies to attempt to unify and fix meanings to particular power-laden articulations of local cultural identities. As cities, such as Liverpool, are re-imagined, regenerated, and remade, some popular memories are re-circulated in the name of heritage and the promotion of cultural regeneration (here again the Beatles in Liverpool provide a strong case). However, when material environments—such as buildings, houses, venues, cafes, and workplaces described by Tim Edensor as storehouses of social memory—are torn down, the disappearance of physical space catalyzes the erasure of the collective memories of those spaces. Thus, the city not only provides important spaces for collective remembering, but also, and just as crucially, for collective forgetting.

Theme 1: Mapping the social clubs of Liverpool 8

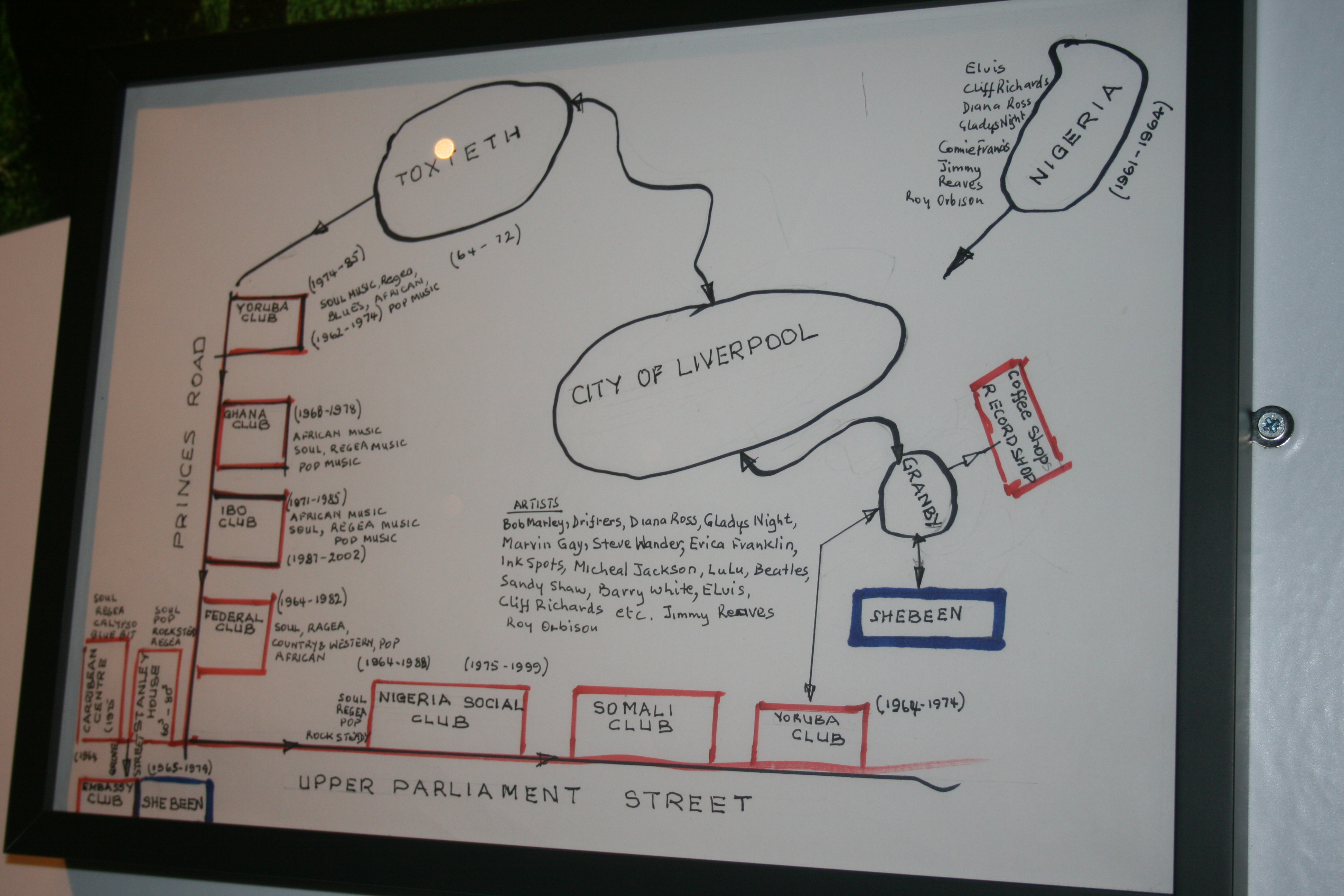

This documentary project was inspired by a map of the area drawn by Chief Angus Chukuemeka for a museum exhibition on Liverpool popular music.

Courtesy of National Museums Liverpool

Chief Angus Chukuemeka’s map locates approximately ten social clubs and a small number of “shebeens” (or “blues”—unlicensed venues), sites for socializing, drinking, music, and dancing. Like many interviewees for this documentary, Chief Angus described the emergence of the L8 social clubs as a response to local racism and global, postcolonial Black experiences:

As Chief Angus remarks, community groups set up the social clubs to maintain links to different heritages, musical and diasporic identities. Stephen Nze—whose father was Ibo from Nigeria—tells us of the presence around the “Black Atlantic” of links between music and diaspora via the Ibo Club: “The music that was playing in those clubs at the time was basically everything that was coming out of America, you know? So it was soul, R’n’B, and reggae basically. And then of course, because it was an African club, African music, Nigerian music.” Today only two clubs remain—the Caribbean Centre and the Nigeria Centre—and there are few physical traces of the social clubs once located in Georgian townhouses that lined Prince’s Road and Upper Parliament Street. Some of these buildings were demolished; others have been converted into flats. What had the clubs been like? What of their significance within the community? Where were the social clubs and what had they been used for? Some of the respondents were quite specific and provided vivid recollections of the social clubs (Stephen), while other painted more romanticized views of the social clubs and the era (Charlie C.):

Against Charlie’s nostalgic yearning to “go back,” other accounts noted the significance of the social clubs in the context of the everyday struggles for people at the time. Many of these narratives stressed the importance of the social clubs for Black communities and identities, in terms of leisure time and space, especially during difficult economic times. Stephen recalled the meaning of the Ibo Club for him, his family, and the L8 area:

While the social clubs originated from the unique patterns of African and African Caribbean settlement in Liverpool, the clubs were not exclusive to members only from those communities. Across the participants with whom we spoke, the social clubs were described as being frequented by a mix of folks: Blacks and whites, visiting merchant sailors and American GIs, DJs and musicians (both local and from further afield), university students, local families, as well as hustlers, grifters, and sex workers. It should be noted further that there is no singular construct of “Black” Liverpudlians and, as noted by Stephen Small, many are “mixed race.” The “crumbling cosmopolitan village” in L8 was described as having an important impact upon the young aspiring musicians in the area at the time.[iii] In sum, the area was remembered as “thriving” and “alive” with a diverse mix of people and music.

Theme 2: Lines of color and belonging in the city

In Liverpool during the era when the social clubs were most active (1960s-1980s), participants spoke of the politics of space marked out by a stark territorialization of the city and closely linked to racial relations, localities, and popular music. There were clear lines of belonging that defined where one could and could not safely go based on the color of one’s skin. The cultural theorist Stuart Hall described the policing and maintaining of such physical and symbolic boundaries as an attempt at cultural “closure” and “purification”:

[W]hat unsettles culture is “matter out of place”—the breaking of our unwritten rules and codes. Dirt in the garden is fine, but dirt in one’s bedroom is “matter out of place”—a sign of pollution, of symbolic boundaries transgressed, of taboos broken. What we do with “matter out of place” is to sweep it up, throw it out, restore it to order, bring back the normal state of affairs. The retreat of many cultures towards “closure” against foreigners, intruders, aliens, and “others” is part of the same process of purification.[iv]

During the interviews, many respondents spoke of this symbolic closure of city centers and the racialised constructions of Blackness as “matter out of place.” For example, in the following excerpt, Joe Ankrah of The Chants described the difficulties in arranging his group’s first live performance in late 1962 at the Cavern Club being backed by the Beatles:

Indeed, all interviewees mentioned they were subjected to racialized abuse, verbal taunts, and the weight of the “white gaze” when in Liverpool’s city center. When Joe and the Chants arrived at the Cavern, they were refused entry; simply walking through town to get to the Cavern was “an ordeal.” This memory provides but one example of exclusion from Liverpool’s city center. Against this, L8 was a safe haven which DJ Ivan, “the Russian,” remembered as “the only place we was accepted … [there was] some sort of strange color line in town” that was subtly enforced when doormen would tell him “‘you haven’t got the right tie on tonight,’ that sort of thing” to deny him entrance to city center music venues. For Donna and her group Distinction, city center venues were entirely off limits: “we could not go to clubs in town ... we didn’t venture to certain parts of the city center.” Even within Liverpool 8, the Rialto Theater—a cinema whose white patrons’ memories were reported on by Glen McIver—was off limits to some local residents with only “certain nights for Black people.” Burned to the ground in the 1981 urban protests (also called the “Toxteth riots”), the Rialto is remembered by Donna as a local landmark “in the middle of the ghetto where [Black] people couldn’t go.” Given the highly charged racial politics of space—the territorialization of where one can and cannot go, where one feels safe or unsafe—the L8 social clubs were remarkable for providing a shared communal focus. This communal strength, according to DJ Ivan, was the vital significance of the L8 social clubs. Ivan recalled they created “a sense of purpose, a community direction, because things could get organized ... it gave us strength in a way, there’d be people there for us, and the music was there for us.”

Theme 3: The vanishing social clubs of L8

Although the L8 social clubs had flourished, most had closed by the end of the 1980s, and today there is little physical evidence remaining of their existence in the streets of L8. In the 1980s, Liverpool (and the UK more generally) was experiencing a prolonged period of economic recession and social unrest. In L8, Stephen Nze recalls “the whole scene was dead. ... What happened? Thatcher. ... The individual takes out the community. ... The fabric of the community was decimated. ... The [1981] riots broke out because the place was dead broke.” Stephen argues that the decline of the social clubs was a direct outcome of Thatcherism, in particular the politics of neoliberalism, cuts to the welfare state, the slow closure of the port, and the restructuring and privatization of housing in the area. Many people [were] moved away; terraced housing in the area was demolished along with many clubs along Prince’s Avenue and Upper Parliament Street. Stephen’s commentary on the “decimated fabric of the community” laments the loss of both physical, built environments and its social networks, echoed in comments from Charlie C., Donna, and Gloria:

While Gloria perhaps romanticizes the social clubs and the kinds of leisure that she had and that young people today “will never have,” her statement also highlights the lack of historical and political awareness about the social clubs and the communities once centered in L8. Four young people (ages 18-25) were involved in co-producing the documentary film and, despite having grown up in the area, they had little sense of the history of the L8. One young participant commented that his aunt would point to this or that location of a former social club as they drove by together in a car. However, such gesticulations seem to have had little impact, as the young people could not readily imagine that what was now a residential townhouse was once a bustling social club. The young participants expressed almost no knowledge of the area’s past and the significance of the social clubs in the history of Black people in Liverpool. This “social forgetting” is perhaps due to the fact that little remains of the physical presence of the social clubs in the area; there is not much to remind young people of what was there. In this regard, when asked why he had drawn his map of L8, Chief Angus Chukuemeka explained: “For the young people, their parents and grandparents were heroes and it’s good for them to know where those clubs were, because those clubs were a part of our history, the history of Black people in Liverpool.”

Conclusion

There has been increasing attention to mapping “hidden histories” and oral histories, including Rob Strachan’s oral histories of Black musicians involved in The Beat Goes On exhibition at National Museums Liverpool. Like Strachan, I contend that oral history accounts are not only “important in their own right,” but also provide critical insights into the everyday lives, economic conditions, political struggles and social spaces in a distinctive area of the city.

While the L8 social clubs have been largely erased from the urban landscape, documentary practices represent one means to archive memories of this contested terrain in Liverpool. The documentary was produced also with the intent of putting these memories into wider circulation, via Internet sites and screenings at local events and in community centers. Without circulation, there is a risk that these cultural memories and legacies of L8 will remain hidden, particularly to young people who currently live in the area and struggle to find community spaces for music and leisure. In this sense the documentary process serves to connect (what appear to be) personal troubles to wider public issues. That is, documentary filmmaking calls attention to how local communities in L8 responded to the social, historical and spatial impress of racism and social inequality—problems which remain in Liverpool as elsewhere. As Chief Angus cautioned, to forget about the L8 social clubs is to lose part of the history of Black people in Liverpool. If the connection to a city is always mediated by memories, such memories must also be shared, or perhaps, like the L8 social clubs, they too will largely vanish and become forgotten.

Notes

The documentary film L8: A Timepiece was co-produced with URBEATZ: Yaw Owusu, Kofi Owusu, Jernice Easthope, and Janiece Myers. A full version is available at: http://vimeo.com/16294410.Thanks go to URBEATZ and to the participants who generously spoke with us. Thanks also are due to Leeds Metropolitan University’s Carnegie Research Institute for funding the project.

[i] Orhan Pamuk, Istanbul: Memories of a City (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), 216.

[ii] Stated in an advertisement “To get close to the Real Thing, get Four from Eight”, New Musical Express, (10 July 1977): 28-29.

[iii] John Cornelius, Liverpool 8 (Midsomer Norton: John Murray Publishers, 2001 [1982]), 63.

[iv] Stuart Hall, Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices (London: Sage, 1997), 236.

Brett Lashua is a lecturer in the Carnegie Faculty at Leeds Metropolitan University. His scholarship is concerned primarily with arts, leisure and cultural practices (especially popular music) as well as questions of the politics of urban spaces, social inequalities, and history.

Media Fields Journal

Media Fields Journal

Reader Comments